Biblical and Theological Commentary on Tolkien's Letters, Part 1

Letters #5, #17, #40, and Prayer in Tolkien's Letters

(avg. read time: 5–10 mins.)

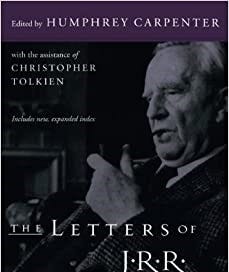

To my knowledge, no one has yet done a biblical and theological commentary on the letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. But whether or not that is the case, I have been wanting to do such a project for several years now. And like my previous Tolkien Tuesday series, this will be something experimental in anticipation of more conventional projects that have been pursued in commentaries on his major fictional works. There is no easy way to divide this up, so I will simply be doing it in seven arbitrary parts. As a fair warning, these will in no way be balanced in terms of length. The first two parts and the last part will be relatively short (but not too short) and others will be quite extensive, not least because they will involve letters that I have already written about at some length.

Letter #5 (12 August 1916 to Geoffrey B. Smith)

The first letter of relevance to this commentary is also one of Tolkien’s earliest letters, Letter #5. The occasion for this letter, which was also to be passed on to Christopher Wiseman, was to talk about the death of fellow T.C.B.S. member Rob Gilson. This had caused Tolkien to be reflective about Gilson and about the state of the T.C.B.S. in general, now that its fate seemed so precarious. I explained in my Tolkien review what the T.C.B.S. was all about:

As I have illustrated to this point, each of them has artistic gifts: Tolkien tells and writes stories while also inventing languages; Wiseman composes music; Gilson draws and designs; and Smith writes poetry. Through their various gifts, they hoped to establish a sort of medieval renaissance in the modern age into which they could invite those unanchored in the world who were otherwise destined to mere disorientation, disillusionment, and despondence. They hoped to inspire—and, according to Tolkien in Letter #5 … to testify for God and Truth—with clarity of vision, artistry of truth, and love of true beauty without necessarily telling people what to do (as John Garth observes in Tolkien and the Great War, a book which focuses on much of the same area of Tolkien’s life as this movie does). They aimed to pursue such ends together because they each inspired each other. Tolkien believed that God had granted them such fire to share with one another (he would likewise associate fire with creativity in his own mythology, as God—known as Eru Ilúvatar—creates and sustains all things with the Flame Imperishable).

As Tolkien reflects on the greatness that Gilson has achieved in his death, he differentiates it from the greatness that was part of this design for the T.C.B.S. That greatness is defined as something in addition to holiness or nobility, but not as something less than being holy. But that holiness was also to contribute to another purpose, that of being “a great instrument in God’s hands – a mover, a doer, even an achiever of great things, a beginner at the very least of large things.” Indeed, holiness is not for one’s own benefit; rather, one is made whole and set apart to fulfill the purposes of God, in this case of shining his light in the world.

One is reminded of Jesus’s teaching about his followers being the light of the world (Matt 5:14–16). The light that they shine is a light of testimony, no more meant to be hidden than a city on a hill or a lamp in a room. For a lamp to be lit only to be put under a basket would indeed be the equivalent of mistaking holiness as being for one’s own sake, that it exists for one’s own benefit, and not to testify to the God who makes holy. Instead, the lamp is meant to be put where it can shine on the rest of the house. In the same way, Jesus tells his followers to shine their light before others, fulfilling God’s purposes before others, in order that others should see their good works and glorify the Father who is in heaven.

Likewise, Paul reminds us in 1 Cor 12–14 that the gifts of the Spirit are not for the benefit of the person they are given to. Rather, these gifts are distributed according to God’s purposes and for the benefit of others. Tolkien operates under the same assumptions when referring to the gifts God bestowed on the various members of the T.C.B.S.

Of course, the greatness that is linked to the designed purpose of the T.C.B.S. is of one piece with the greatness that Gilson achieved in fact. For as Tolkien says, the greatness hoped for the T.C.B.S. must be animated by the same holiness of courage expressed in suffering and sacrifice. This is, again, a notion formed by his and their upbringing as Christians, being reminded of Christ’s blessing of those who are persecuted for the sake of righteousness and his gospel (Matt 5:10–12), of his directive repeated in each of the Synoptics to deny oneself, take up one’s cross, and follow him (Matt 16:24 // Mark 8:34 // Luke 9:23), as well as his teaching that “no one has greater love than this, that he should lay down his life for his friends” (John 15:12). This holy courage is that of living the cruciform life of love according to the image of Christ and it is also what must animate the continuing pursuit of the T.C.B.S., which Tolkien describes as testifying “for God and Truth in a more direct way even than by laying down its several lives in this war.” This last statement in particular should leave no doubt about the Christian purposes of the T.C.B.S., as well as its resonance with these various biblical teachings.

Of course, with one of the founding members of the T.C.B.S. dead, the possibility must now be reckoned with that the legacy of the T.C.B.S. will need to be carried on by some less-than-desirable proportion of the society. Tolkien prays that he, Smith, and Wiseman, the three remaining members, should all live through the war and fulfill their commission. But he must also acknowledge that the work of the T.C.B.S. may only done by as few as one of the members, “and the part of the others be trusted by God to that of the inspiration we do know we all got and get from one another.” Not for the last time in Tolkien’s work do we thus see the importance of providence in his theological thinking. And indeed, in God’s providence, it proved that Tolkien was almost the sole carrier of the purpose of the T.C.B.S. and his was the impact that the broader world felt. As fruitful as Tolkien’s imagination was, he could not have imagined the impact he himself would have in following through on this mission of the T.C.B.S., nor could he have imagined how far-reaching it would continue to be almost fifty years after his death. Such are the wonders of God’s providence.

Prayer

Before moving on to the next letter of relevance, it is also worth noting that this is only the first such occasion in which Tolkien’s prayerful capacity is demonstrated as he reflects on the death of his friend. Prayer would naturally be part of his regular Mass attendance and as part of a prescription for his confessions that he gave before receiving the Eucharist. And aside from Letter #5, one can also find references to prayer in Tolkien’s correspondence in Letters #42 (January 1941), #45 (June 1941), #54 (January 1944), #64 (April 1944), #68 (May 1944), #89 (implicitly by reference to ritual; November 1944), #92 (December 1944), #96 (January 1945), #99 (May 1945), #113 (Septuagesima [January 25] 1948), #115 (June 1948), #191 (July 1956), #238 (July 1962), #250 (November 1963), #306 (October 1968), #310 (May 1969), #312 (November 1969), and #315 (January 1970). In Letter #54, he mentions a number of praises that he had learned and that he advised his son Christopher to learn while he was at war. Letter #113 also shows a keen attitude of repentance that comes from an experienced life of prayer and confession. Letter #191 specifically refers to the Lord’s Prayer. On that note, one particularly amusing case of Tolkien praying was in an event related by George Sayer (a frequent source of stories about Tolkien). Tolkien visited George and Moira Sayer in 1952 and George showed him a tape recorder, which was a piece of technology completely alien to Tolkien. When he heard that it could record and play back voices, he joked that it sounded like it was possessed. To perform an exorcism on it, he had Sayer record him saying the Lord’s Prayer in the dead language of Gothic, because why not? He also discusses the topic of prayer in his fantasy in Letters #153, #156, #246, and #297, which we will return to at other times. Finally, he translated the Lord’s Prayer/Pater Noster into his invented language of Quenya, a piece called Átaremma (“Our Father”). This went through at least six versions, which are published in the forty-third issue of Vinyar Tengwar. The final version is as follows:

Átaremma i ëa han ëa [who art beyond the universe]

na aire esselya,

aranielya na Tuluva,

na kare indómelya

cemende tambe Erumande.

Ámen anta sira ilaurëa massamma,

ar ámen apsene úcaremmar

siv’ emme apsenet tien i úcarer emmen.

Álame tulya úsahtienna

Mal áme etelehta ulcullo.

Násië.

(One should also note that he wrote Quenya translations of Ave Maria [Aia María; four versions], the Litany of Loreto [incomplete translation in Loreto], Sub Tumm Praesidium [Ortírielyanna], Gloria Patri [Alcar i Ataren], Gloria in Excelsis Deo [Alcar mi tarmenel na Erun], and a Sindarin translation of the Lord’s Prayer [Ae Adar Nín].)

Letter #17 (15 October 1937 to Stanley Unwin)

Stanley Unwin had noted the complaint of Richard Hughes that as much as The Hobbit is aimed at children, there are certain parts of it that are too dark for children. In response, Tolkien reiterates—with the even-more strengthened conviction of a sub-creator whose work has gone through the scrutiny of others—a theme that he continues to emphasize particularly throughout this period in which he writes LOTR. He insists that Hughes’s complaint is a common problem, “though actually the presence…of the terrible is, I believe, what gives this imagined world its verisimilitude. A safe fairy-land is untrue to all worlds.” As much time as Tolkien famously devoted to maintaining the internal consistency and integrity of his sub-creation, he also wanted to ensure that his sub-creation was realistic in terms of reflecting accurately the character of the Primary World. Sub-creation in its truest form comes from a desire to be creatively truthful. To lie as part of sub-creation is to corrupt the result and to deny the reality of the image-bearing identity of humanity (I have noted in my series on Tolkien’s theology of sub-creation how crucial this biblical teaching of humans being the image-bearers of the Creator was to Tolkien). As long as terrible evil is part of the Primary World, it is only honest for the Secondary Worlds to reflect that fact in whatever way they can.

Letter #40 (6 October 1940 to Michael Tolkien)

One other area in Tolkien’s earlier letters that one can see the influence of biblical instruction is in comments he makes to his son Michael when Michael was enlisted in the Army. He sympathizes with Michael that it feels in the Army as it does in peacetime that we become engrossed in treating everything as a preparation for something else. But he insists, “At any minute it is what we are and are doing, not what we plan to be and do that counts.” This statement is informed by such texts as Jesus’s teaching on worry (Matt 6:25–34), that each day has enough troubles of its own and one should trust in God and be about his work now rather than worrying about tomorrow, and the warning in James against boasting about tomorrow (Jas 4:13–17). In the latter case in particular, it is made clear that planning for the future can become a means of avoiding doing what is right today.