(avg. read time: 16–32 mins.)

In another case of synoptic analysis, alongside the three examples I have provided to date, today I will be looking at another instance of “quadruple tradition.” In this case, the quadruple tradition is the one miracle (besides the resurrection, of course) that appears in all four Gospels: the feeding of the 5,000. This is another story for which I already composed comparisons in my work for my Historical Jesus class. There are yet many more texts that will be subject to similar analysis in the synopsis commentary I would like to write eventually (Matt 3:1–17 // Mark 1:2–11 // Luke 3:1–9, 15–18, 21–22 // John 1:19–34; Matt 21:1–9 // Mark 11:1–10 // Luke 19:28–40 // John 12:12–19; Matt 26:6–13 // Mark 14:3–9 // Luke 7:36–50 // John 12:1–8; Matt 26:21–25 // Mark 14:18–21 // Luke 22:21–23 // John 13:21–30; Matt 26:30–35 // Mark 14:26–31 // Luke 22:31–34 // John 13:36–38; Matt 26:47–56 // Mark 14:43–52 // Luke 22:47–53 // John 18:2–12; Matt 26:69–75 // Mark 14:66–72 // Luke 22:56–62 // John 18:15–18, 25–27; Matt 27:11–14 // Mark 15:2–5 // Luke 23:2–5 // John 18:29–38; Matt 27:15–23 // Mark 15:6–14 // Luke 23:17–23 // John 18:39–40; Matt 27:33–38 // Mark 15:22–27 // Luke 23:32–34 // John 19:17–27; Matt 27:48 // Mark 15:36 // Luke 23:36 // John 19:29; Matt 27:57–61 // Mark 15:42–47 // Luke 23:50–56 // John 19:38–42; Matt 28:1–8 // Mark 16:1–8 // Luke 24:1–9, 12 // John 20:1–13, 18; Matt 28:9–10 // Mark 16:9–11 // Luke 24:10–11 // John 20:14–18).

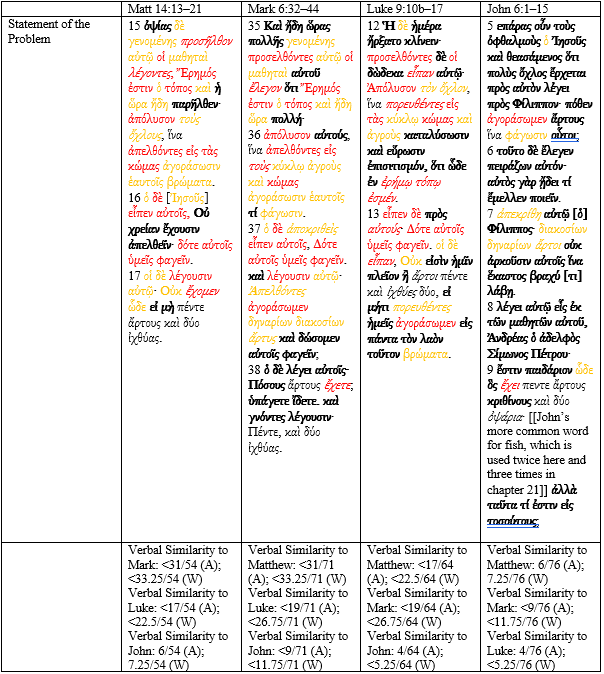

The following tables supply a textual comparison of each version of the pericope. The words in plain font are common between all four texts. The words in red font are common between three of the four texts. The words in orange fonts are common between two of the four texts. The words in bold font are unique to each Gospel. The words in italics are alternate forms of words that appear in multiple texts or synonyms. The words in single brackets are variants, while brief comments that do not fit easily elsewhere will be in double brackets. For each text, I will give two scores of similarity (which do not account for rearrangement) to each of the other Gospels: one will be cases of absolute matching and the other will be cases of “weighted” matching, not counting variants (assigning a value of 1 to perfect matches, 0.75 to alternate forms of the same word and 0.5 to synonyms). There is no easy way to account for variation in word order in these similarity scores, thus my only solution to make note of these variations is to put a < symbol next to scores to signify that the verbal similarity is actually less than the calculated score would indicate because of the difference in word order where the wording is otherwise similar. The Greek is taken from NA28.

1) Mark and Luke do not explicitly connect this story with the preceding one, except by the generic connective καί. Matthew’s opening is an explicit link to the previous account of John the Baptizer’s death by the command of Herod. That Jesus heard about this and withdrew to an uninhabited place for solitude implies—more strongly than the parallel accounts in Mark and Luke—that he took this action (at least in part) to mourn.

2) John also directly links this story to the previous one, though his previous story is about Jesus healing a lame man on the Sabbath and the consequent confrontation with the Jewish authorities about his authority.

There are no common elements of language shared across all Gospels in this particular segment, but they do share the basic events of Jesus moving to a new location and the crowd(s) following him. Some of the variations—such as the uses of synonymous verbs like ἀναχωρέω instead of ἀπέρχομαιand the references to the crowd in the singular or plural—are due to differences in style.

Another minor difference is in how Matthew, Mark, and John (but not Luke) feature Jesus going to the other side of the Sea of Galilee (only John names it and he adds that it is also called the Sea of Tiberias), yet John does not refer to the boat. Perhaps John regards the detail as unnecessary at this point in the story, or perhaps he means to imply that Jesus walked around the sea to the other side. On the basis of John alone, the conclusion is not straightforward. Ultimately, the answer likely depends on how one views the relationship of John and the Synoptics. As I see it, there is no reason to think that John is necessarily saying that Jesus did not get in a boat.

But even the Synoptic authors differ in several details beyond style. Neither Matthew nor Mark name Jesus’s destination—it is enough for them that the place is in the wilderness—but Luke says they initially went to Bethsaida, which implies that the miracle took place in the wilderness near its vicinity (9:12). This would indeed seem probable as an approximate location of the feeding miracle, since Jesus would be crossing over to there from his typical base of operations in Galilee. John also states that Jesus crossed over from this location to Capernaum, which makes sense if Jesus had done the miracle near Bethsaida (6:17), as Capernaum is on the western half of the sea and Bethsaida is on the eastern half. Uniquely among the Gospels, he will even mention Philip later, who he says elsewhere was from Bethsaida (1:44; 12:21). Matthew does not explicitly say, but the fact that Jesus and the disciples end up at Gennesaret after crossing over in the boat (14:34) indicates that they were crossing over from the eastern half, as Gennesaret was near Capernaum. The only point from any of the Gospels that causes potential conflict with this location, and not mere difference in narrated detail (which could still be compatible) is Mark’s reference to Jesus sending the disciples in the boat to the other side πρὸς Βηθσαϊδάν after this story in Mark 6:45. The phrase is typically translated as “to Bethsaida,” which would mean that the miracle happened on the other side of the sea from Bethsaida, opposite of the other Gospels. But considering that Mark agrees with Matthew in placing Jesus and the disciples at Gennesaret after crossing the sea (6:53), it would seem that the text of Mark itself suggests an alternative translation for πρός in this instance, which could mean “over against” or “opposite.” That would mean that Mark is identifying the general location of the miracle in the same way Luke does. Alternatively, if the more typical translation is to be preferred, it could be that the instruction was to go towards Bethsaida en route to the other side. I am inclined to think the first is more likely, but I am not interested in providing an extensive judication on the matter here, as that is beyond my scope.

They also differ in the verbs they use to describe how the crowds learned of Jesus’s departure. John’s account features Jesus leaving with the crowds simply being drawn to him because of what they have witnessed so far. But according to the Synoptic authors, the crowd heard (Matt 14:13), saw (Mark 6:34), or simply knew (Luke 9:11) that Jesus had left. Of course, these verbs need not represent mutually exclusive claims as they are all ways of referring to the gain or possession of knowledge. As such, this could be one of three instances in his telling of the story when Luke provides a more general associated verb in place of more specific verbs in Matthew and Mark (9:11b, 12b. 13b).

Finally, they differ in how they describe Jesus’s action for the crowd once they have arrived. Matthew refers to Jesus as having compassion on the crowd and healing (θεραπεύω) their sick. Mark refers to Jesus as having compassion on the crowd because they were like sheep without a shepherd (a clause unique to Mark’s version; cf. Num 27:17; 2 Chron 18:16; Ezek 34:1–16; Zech 10:2; Matt 9:36) and teaching (ἤρξατο διδάσκειν) them many things. Luke combines these two narrations as he refers to Jesus as speaking (λαλέω) to the crowd about the kingdom of God as well as providing healing (ἰάομαι) to those who needed it. Interestingly, the verbs describing how the crowd learns of Jesus’s departure contrast with what they receive from Jesus. In Matthew they hear about Jesus and they receive healing that they can witness for themselves. In Mark they see Jesus leaving and they hear teaching from a Jesus who is acting as their shepherd. The contrast is not as apparent in Luke, but perhaps the more general verb anticipates Jesus’s broader response to the crowd in providing them with both teaching and healing. The difference between Matthew and Mark on this point is interesting, since Matthew regularly emphasizes Jesus’s teachings and Mark typically emphasizes Jesus’s actions. On the other hand, Matthew has several asides on other miracles Jesus performed beyond the ones given extensive narration (4:23–24; 8:16–17; 9:35–36; 15:30–31; 19:2; 21:14). It seems to be this emphasis that is operative in this episode. For whatever reason that Mark uniquely uses the sheep imagery (and for whatever reason Matthew has placed such a note at 9:36 instead), that reason also explains his emphasis on Jesus’s teaching activity.

Furthermore, on the point of healing, Matthew, Luke, and John use different vocabulary in reference to Jesus’s healing activity. Matthew uses the typical θεραπεύω. Luke uses the unusual ἰάομαι, which appears eleven times in Luke, more than the other three Gospels combined. John uses his typical term for Jesus’s miracles (σημεῖα) and specifies those miracles as healings with a longer description (ἃ ἐποίει ἐπὶ τῶν ἀσθενούντων). This language and the larger context of the story show that John is referring to Jesus’s actions prior to this episode rather than during it, specifically the two sign narratives prior to this one (4:43–54; 5:1–9).

Finally, John adds more information unique to his Gospel. Only John explicitly says that Jesus and the disciples are sitting on the mountain. This is somewhat surprising for John because he refers to mountains less often than any of the other evangelists. But in light of the subsequent narration and Jesus’s discourse in this chapter, this imagery could contribute to the Moses imagery and evocations of the exodus and wilderness wandering. Likewise, only John relates this event to the Passover. On one level, this connection fits with the Johannine tendency to link Jesus with Jewish symbols, rituals, and holy days (2:6, 13, 16–23; 5:1, 9; 6:4; 7:2; 9:14; 10:22; 11:55; 13:1; 19:14). On another level, this connection explicitly provides the audience with a framework for interpreting this event. This is not to say that John invented these associations. All of the Gospels portray Jesus as acting symbolically, deliberately evoking and quoting the Scriptures, and teaching about the eschatological significance of his ministry (other messianic and prophetic figures referenced in Josephus do all of these things as well). Thus, it is probable that this association goes back to the deliberate action of Jesus (especially if the subsequent discourse is reflective of Jesus’s teaching). But John is still unique in how consistently he draws attention to these associations.

These segments feature more commonalities in language than the previous segments with the use of the conjunction ἵνα and the reference to five loaves and two fish. The authors clearly regarded this precise account of the amount of food available as essential and immutable. However, John uses a different word for “fish” than the Synoptic writers (ὀψάριον vs. ἰχθύς). This word is unique to John and it is generally used for fish that has been cooked or prepared (the exception being in 21:10, which may still indicate the anticipation that the fish will be cooked).

These segments involve several other similar stylistic variations. Luke refers to the Twelve, rather than simply “the disciples.” None of the Synoptic authors use the exact same form of λέγω in the first case (and Luke still provides variance in the second case). Luke spells the word for “fish” in a slightly different manner. The more abridged Matthew and Luke do not refer to how much money the disciples think they would need, unlike Mark and John. Mark and John also pluralize “bread” differently. Most significantly, Matthew, Mark, and Luke each have unique ways of saying that the time was late in the day, while John shows no concern for the matter. Interestingly, apart from these and other stylistic variations (such as in how the disciples say how much bread and fish they have), Matthew is virtually an abridged equivalent of Mark.

On the other hand, Mark and Luke provide different arrangements and some different content of the dialogue between Jesus and the disciples. In Mark the disciples begin with citing both the location and the time of day as justifications for their concern and then implore Jesus to send them away so that they can get food for themselves in the surrounding countryside and villages. Jesus responds by telling them to give the people something to eat. The disciples are flummoxed by this response and ask if he really does want them to go and buy 200 denarii worth of bread for these people. Jesus then asks how much bread they have, to which the disciples respond that they have five loaves plus two fish.

Luke the narrator mentions the time of day, while the disciples do not. The disciples actually begin with telling Jesus to send the crowd away so that they can go to the surrounding countryside and villages to find lodging and something to eat (in the latter case, Luke uses different vocabulary than Mark, as he uses the language of “finding” rather than “buying” and of a hapax legomenon referring to something to eat rather than Mark’s reference to bread). Then they justify this imperative with the fact that they are in the wilderness. Jesus tells them to give the people something to eat. The disciples respond by fronting their lack of adequate food—having only five loaves and two fish—and saying there is nothing to be done unless they should buy food for all of these people, although they do not state the cost like in Mark.

Luke is more abridged in some areas and more expansive in others in comparison to Mark. He also uses a mix of special vocabulary and more general verbs in place of what Mark writes. The arrangement of the dialogue is not necessarily more logical one way or the other. Probably the best way to account for these differences is to suggest that they are due to the different sensibilities of these authors in terms of arranging the material of the story and using the proper language and style to narrate it (e.g., Luke addresses the concern of lodging as well as food, while Mark may have taken the former for granted). Additionally, Luke seems to have excised material he seems to have regarded as extraneous to the story, which Mark included because he is more precisely and directly reflecting eyewitness testimony. John may provide further support of this interpretation as he generally matches Mark’s arrangement and uniquely shares with Mark the detail about the 200 denarii while also adding more detail himself.

John uniquely has Jesus posing the question of buying food, but he also adds the unique note that Jesus asked this question to test Philip because he already knew what he was about to do. This is an interesting difference as John attributes the question to a different source, but also provides theological interpretation to the event—which could well be a reasonable inference from how the rest of the story unfolded—lest some might misunderstand Jesus’s purpose in asking the question. It is as if John knows the problem this difference in the narrative could create, but he is preemptively giving theological justification for it. But this account is still an odd one, as John’s account is the only case in all four Gospels in which the verb πειράζω is attributed to Jesus. In any case, it is unclear if one strand of tradition melded together separate lines of dialogue and attributed them to the disciples or if John is separating and re-attributing what was originally joined together. This factor of the difficulties the difference could create, along with the fact that John has to provide a preemptive explanation for this feature, as well as John’s greater precision in narrating some of the details of this episode may all plausibly indicate that John’s testimony is more precisely reflective of an earlier reminiscence than, by this reading, the more conflated Synoptics.

John also uniquely specifies Philip and Andrew among the disciples as having speaking roles. Again, John seems to be narrating this account with greater precision and the reference to them could be due to John having a personal connection with Philip and Andrew (cf. 1:40, 43–46; 12:21–22; 14:8–9). Furthermore, the idea that Jesus would single out Philip for this question is plausible if the miracle does take place in the vicinity of Bethsaida, Philip’s hometown, as Luke claims and as the other Gospels align with.

In John the five loaves and two fish come from a lad. In the absence of more information in the Synoptics (which is not necessarily a matter of conflict so much as omission versus presence), one might infer that the disciples were short on food but could possibly get by with that amount of food for themselves. Of course, the unique appearance of this character in John could be another indication of John’s greater precision, which one could account for easily if John is an eyewitness.

Finally, John mentions that the loaves are barley loaves. On the one hand, barley was cheaper than wheat, so this note may accentuate what this lad/the lad’s family could afford. On the other hand, the Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread were associated with the barley harvest; thus, this reference could further stress the Passover timeframe for this story. It is also possible that this detail adds to the amount of potential connections to 2 Kgs 4:42–44, another feeding miracle, but that seems less plausible given its only superficial similarities.

The words all four Gospels share are some form of the phrase λαμβάνω ὁ ἀρτός. They feature more variance in reference to the two fish, as all the Synoptics mention the two fish once, Mark mentions them twice, and John does not repeat the count of the bread and fish or even use the same term for fish, as noted above. And while all of them refer to the people as reclining for a banquet or feast, they use three different verbs (ἀνακλίνω, κατακλίνω, and ἀνάκειμαι) and two different forms of one verb (ἀνακλιθῆναι and ἀνακλῖναι). Despite these stylistic differences, the reiteration of the elements of the meal was obviously regarded as essential to maintain by all authors.

Likewise, all the Synoptics note that all of these people ate and were satisfied (or in Luke’s case, they ate and all were satisfied). John does not repeat this language, but he conveys the same point in his own words that everyone had as much as they wanted to eat. In all four Gospels, this is the first indication that the miracle of multiplication has taken place, since the miracle itself is never narrated. The fact that none of them, not even the more detailed account of John, elaborate on this point by actually narrating the increase of bread and fish illustrates that none of the writers felt free to add to this particular part of the miracle account (much like none of them elaborate on the resurrection accounts by actually narrating Jesus’s resurrection itself).

What the writers do describe about Jesus’s action is almost identical across the Synoptics. The verbs and their sequence are exactly the same—even if the precise forms of those verbs vary—up until Jesus hands the bread over to his disciples. Matthew then transfers the verb δίδωμι to the disciples as well, while Mark and Luke use the more precise παρατίθημι as the verb for the disciples’ action to the crowd. John once again uses his own words to describe the same events. He does not feature Jesus looking up to heaven—John only uses ἀναβλέπω in John 9 for the blind man receiving sight—or blessing the meal, but he does give thanks (εὐχαριστέω; cf. Matt 15:36; 26:27; Mark 8:6; 14:23; Luke 22:17, 19; 1 Cor 11:24). This is not a typical verb for John—or for any of the Gospels—and the only other context in which it appears is in 11:41 prior to the raising of Lazarus. Interestingly, these are also the only signs in which Jesus prays/offers thanks prior to performing them. If John is trying to make any particular point by using the verb in these two cases, it is unclear.

Jesus also does not explicitly break bread in John, as perhaps John would think such an action to be implied, whether due to prior knowledge of the Synoptic tradition on the part of his audience or due to the expected practices of distributing bread (if the eucharistic undertones are here, which is debatable, one might argue that the eucharistic framing here and in the subsequent discourse support the idea that John could simply imply the action of breaking the bread). John also uses a related, but more precise verb for distribution (διαδίδωμι). This is a verb applied to Jesus, not to the disciples. It is possible that John has conflated the actions of Jesus and his agents in line with his tendency to have Jesus take a more active role at every level of the narrative (such as with Jesus being the one to pose the question earlier; cf. John 10:15–18; 13:26–27; 18:1–9), and as is also not uncommon for leaders to be attributed actions they instructed their followers to do.

But yet again, the arrangement of the material is not strictly fixed between all Gospels. Luke and John mention the 5,000 in this segment, rather than in the next one that properly parallels Matthew and Mark (though I note the parallel language below). Perhaps this feature indicates the different emphases of the authors via their end stresses. In that case, what is most important about this miracle for Matthew and Mark is the number of people who partook of it. What is most important about this miracle for Luke is the satisfaction of all who ate as well as the overabundance of food. What is most important about this miracle for John is how it points to Jesus’s identity and how the crowds misunderstood it. All of these features are present in all of the Gospels, whether in the stories themselves or in their contexts (Matt 14:28–33; Mark 6:50–52; Luke 9:7–9, 18–20), but the narrators arrange the stories differently to draw the audience’s attention to different aspects.

Matthew, Mark, and John all refer to grass in the area where this miracle took place. Matthew’s reference to the grass is most basic, perhaps due to his general abridging tendency in this story. Mark refers to green grass, which could likely be taken for granted, but the additional insignificant detail may be a sign of eyewitness testimony and could indicate a time approximate to the Passover near the end of the rainy season. John simply refers to much grass, which is another incidental detail that does not add to the story, but it may similarly be a sign of eyewitness testimony and of corroboration of his placement of this story around the time of Passover.

Only Mark and Luke add the note on the organization of how the people sat down. Mark describes the people sitting down in groups of one hundred and groups of fifty. Luke simply describes them as sitting down in groups of fifty. On the one hand, this note certainly makes sense because of the need to organize this many people in order to distribute food to them properly. On the other hand, it is not uncommon for more recent interpreters to see a military undertone or overtone to this organizational scheme. Perhaps Luke recognized this possibility as well and thus simplified the reference to groups of fifty (which could still refer to a military unit based on Jewish history; cf. 1 Sam 8:12; 2 Kgs 1:14; 1 Macc 3:55), instead of referring to the more evocative groups of one hundred. While John does not refer to such organization, the conclusion of this episode maintains the impression of the possible military impressions of certain features in this story, if only on the part of the people who partook of the miracle, misunderstood Jesus’s mission, and thus would have tried to make him king by force. If Mark did intend to make such overtones or undertones, the subsequent narrative of Mark’s entire Gospel clarifies that Jesus is not organizing a traditional legion to oppose Rome, but he is organizing the people to whom the kingdom of God is made available.

1) Matthew, Mark, and John immediately follow this episode with the episode of Jesus walking on the Sea of Galilee. Matthew and Mark then proceed to narrate Jesus’s continued healings and his confrontation with the Pharisees and scribes about purity. John uses the episode as a transition to Capernaum, where Jesus uses the imagery of his miracle to declare his identity and the way to everlasting life (which somewhat parallels the giving of the covenant at Sinai, in line with the discourse’s connection with Moses).

2) Luke’s narrative order uniquely features Jesus’s famous identity question—and Peter’s confession—as following this story, though not immediately in any sense except in the narration. This nicely parallels the identity question posed by others in 9:7–9.

The common elements of language that all four Gospels share concern the fragments of food (which Mark does not describe as “leftover” but which the other Gospels describe as such), the twelve baskets (lit. “coffins”) filled with the fragments, and the five thousand men. As with the other elements of shared language, these elements are clearly regarded as essential to the telling of the story, even though, as already noted, the writers have arranged these elements differently. And once more, even where the basic language is the same, the exact forms vary according to how the authors use the words.

The Synoptics differ from John in the verb used to describe what the disciples did with the fragments. The Synoptic authors refer to the disciples as picking up the fragments while John refers to them as gathering the fragments. This seems to be a mere stylistic variance, much like how Mark does not explicitly refer to the fragments as “excess/left over,” but the other Gospels do.

In other cases, one Gospel is more elaborate than others at parallel points. Matthew alone mentions that the count of 5,000 men does not include the women and children who were also there. As Matthew and Mark are the accounts that put the end stress on the number of those who ate, it makes sense for Matthew to accentuate more than Mark that there were more than 5,000 people present in order to accentuate how impressive the miracle was. Similarly, Mark alone finds it necessary to mention that the fragments also included fish. Other writers might have regarded this point as needlessly elaborate and thus would leave it implied. Finally, John features Jesus instructing the disciples to gather the fragments so that nothing would be wasted. Again, this fits John’s earlier noted tendency to make sure Jesus takes more direct and active roles.

But, as usual, John’s greater elaboration in this account does not end there. He adds significant unique information in the last two verses. First, he notes that the people who ate and witnessed the sign regarded Jesus as the prophet who is to come into the world, which fits with how the other Gospels note the crowds regarded Jesus as a prophet of special quality (Matt 14:5; 21:46; Mark 6:15; 8:28; Luke 7:16, 39; 9:8, 19; 24:19; cf. Acts 3:22; 7:37). Second, he notes that Jesus knew what the crowds were intending to do in that they wanted to take him and make him king by force, which I noted before is John’s way of maintaining possible military overtones or undertones in this story, while explicitly insisting that Jesus rejected such an idea. John uses γινώσκω more often than any other Gospel, sometimes in reference to Jesus’s knowledge (1:48; 2:24–25; 4:1; 5:6, 42; 10:14–15, 27; 16:19; 17:25; 21:17). The other Gospels also use this verb in reference to Jesus’s insight (Matt 12:15; 16:8; 22:18; 26:10; Mark 8:17; Luke 8:46), although they also use οἶδα for this purpose (Matt 9:4; 12:25; Mark 12:15; Luke 6:8; 9:47; 11:17). John likewise uses οἶδα as practically interchangeable with γινώσκω in reference to Jesus’s insight (5:32; 6:6, 61, 64; 7:29; 8:14, 55; 11:42; 12:50; 13:1, 3, 11, 18; 16:30; 18:4; 19:28; 21:15–17). These notes are probably inferential—unless one posits that Jesus later told the disciples that he had this knowledge, which is possible.