(avg. read time: 3–6 mins.)

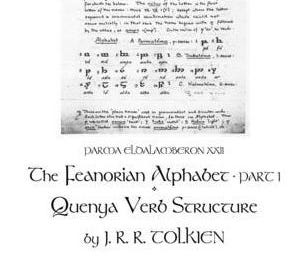

My last Tolkien Tuesday post addressed Tolkien’s early linguistic developments. This time, we will address some late notes of his that accompanied revisions of Quenya. The collection titled “Late Notes on Verb Structure” is part of a much larger collection composing Parma Eldalamberon issue 22 (2015). There is much more in this issue that is of interest to the more linguistically inclined Tolkien fans. But for our purposes in this series, there are still some noteworthy elements in this particular collection of notes.

The first of these notes comes from April 1969, where he writes on the verbal root √EŊE (“exist”). He identifies ëa as the present continuous form translated as “It exists.” When used as a noun, it is defined as “the total created universe” (147). That much can be fairly inferred from the creation story as conveyed in The Silmarillion, but it is interesting that Tolkien goes out of his way to make this note: “Properly cannot be used of God since ëa refers only to all things created by Eru directly or mediately” (147). Thus, he makes clear that this mythological conception of God is still consistent with Christian theology, since he does not think of this God as any other God besides the one he worships, including in terms of his aseity and his transcendence of his creation.1 At the same time, this is a reminder that only Eru is properly spoken of as Creator, as all properly creative activity is either his directly or his action through some medium/mediator (such as the Ainulindalë).

This note also includes a sentence left untranslated: “Eru fai, sî, euva” (147). The footnote translates the sentence as meaning, “Eru (was) before, is (now), will be [after]” (147 n. 18). This resembles descriptors of God in Revelation as “the one who was, the one who is, and the one who is coming” (Rev 1:4, 8; 4:8; cf. 1:18; 4:9–10; 10:6; 11:17; 15:7; 16:5; see the series here for more). That description in turn inspired hymns to this day in acknowledgment of God’s eternality.

As we noted last time that Tolkien’s lexical work overlapped with his thoughts on magic in his mythology, so we see something similar here in another note from around the same time as Letter #155. This one is taken up with different senses of “can”:

‘can’ = have power, strength, ability inherent physically or mentally. √KURU. Cf. *kurwē ‘power, ability’, S curu in curunír ‘wizard’, us[ually] applied to exceptional powers espec. of mind, ability to make one's will effective.* It thus approaches some uses of our ‘magic’, esp. when applied to powers not understood by the speaker, but it does not even then (except perhaps when the word was used by Men) connote any alteration or disturbance of the ‘natural order’, which to the Eldar were either ‘miracles’ performed by agents of the One or counterfeits by delusion (or by means other than miraculous which impressed the uninstructed as supernatural). (151)

This fits what we have observed from Tolkien’s statements elsewhere (including in the previous post and others linked there). It also makes clear that not only could the notion of a “miracle” make sense in Tolkien’s mythology (see also here and here, among others), but people within his stories, such as the Eldar, had a concept of such an event in connection with the One and his agents. Conversely, they thought that others could produce imitations of such works for purposes of deception, domination, and so on. In that same vein, he insisted that the root √TUR should be distinguished from this one, since it has the sense of, “power of domination or dominion: control of other wills, legitimate or illegitimate ‘mastery’; also used of the effect of kurwe upon other persons or things in making them conform to the kurwe of the user” (151). The former term has the sense of magic broadly conceived, which from certain perspectives could include the inherent powers of angelic beings, Elves, and even the abilities of the Hobbits to hide themselves (as in ch. 1 of The Hobbit).

Another note presents Tolkien considering and rejecting an association. But it is still noteworthy for the kind of reflection it represents. As he says, “In Gondorian Quenya. The Rohirrim were called by an adaptation of their own name Eorlingas — Erulingar, which was assoc[iated] with Eru, as if Erulingar was cpd. like Eruhíni, sén (children of God)” (158). However, he marks Erulingar with an X next to it, followed by a note saying, “No — for this would suppose an actual contact between Quenya and Germanic in the ‘Third Age’” (158). While ultimately rejected for reasons of violating historical verisimilitude, the association shows evidence of an outlook of faith among the Gondorians, as well as, seemingly, the piety of the Rohirrim. This fits what Tolkien said in Letter #153: “The Númenóreans (and others of that branch of Humanity, that fought against Morgoth, even if they elected to remain in Middle-earth and did not go to Númenor: such as the Rohirrim) were pure monotheists.” We see in LOTR (see here and here) some expressions of religion, but this designation as such is not necessarily meant to speak to prevalence of religious practice, given Tolkien’s other remarks in Letter #153 and elsewhere.

Finally, there is this remark on expressions about the will:

Q indo < inidō/in'dō: the mind in its purposing faculty, the will. The basic stem NID-, however, was represented by verb nirin, niran, niruvan, ninden, nirnen, inírien, which meant press, thrust, force (in a given direction) and though applicable to the pressure of a person on others, by mind and ‘will’ as well as by physical strength, could also be used of physical pressures exerted by inanimates: níre was the general word for ‘force’, from which was derived níríte, forceful, exerting great thrust or pressure, driving. In the special application to rational will the derivative verb (from indo) indu-, pa.t. indune was used: e.g. indunenyes, I willed it, I did it on purpose.

cf. induinen, n. purpose. cf. the expr[ession] Eru-indonen, by the will of God. cf. turindo, purposeful mind, strong-will, as name Túrin. turindura, done necessarily. (165)

Of course, Tolkien’s stories have much to say about the will, its limitations, and the importance of freedom, especially in LOTR, that we need not dwell on here. After all, we have explored such matters elsewhere. Still, it is noteworthy that this note comes from an author who used allusive expressions for divine action and divine will, such as the simple passive expression that Bilbo “was meant” to find the Ring and that Frodo also was meant to have it (LOTR I/2). And yet, even at this late stage of his writing he could compose ways of explicitly referring to God’s will and action in the world through his invented language.

As a most succinct example, when an interviewer asked who the One God of Middle-earth is, Tolkien responded, “The one, of course! The book is about the world that God created—the actual world of this planet.” Charlotte and Denis Plimmer, “The Man Who Understands Hobbits,” Daily Telegraph Magazine (22 March, 1968), 35 (emphasis original).