(avg. read time: 4–9 mins.)

A new series for this year will provide a preview for a book that is on a slow development cycle. My planned Gospel synopsis commentary is one in which I will take an inductive approach to the Synoptic puzzle as opposed to a deductive one in which a theory is determined beforehand, and the commentary is written accordingly. Of course, there is a lot of scholarship to interact with in addition to the extensive and intensive work required for commentary, meaning that this commentary will take a long time to develop. The basic work of writing out and marking all the Greek by itself took months (though I was working on other projects at the time as well), and it was quite tedious work that still required correction. Even though I am providing previews of the work now, it will be many years before a final project could possibly be available. Part 1 in this series will be made widely available, like two others I have done previously, but all other parts after this will be fully available exclusively to paid subscribers, as is my typical practice for previews of future publications.

The way this will work is on a rotation basis. The commentary proper (not counting introductory matters and summaries of findings) of my book will consist of four parts. The first part will be on “free-floating” texts that are one sentence in length in at least one of the Gospels and appear in a different relative position to the parallel in at least one of the Gospels. The second part will cover texts that are parallel in only two Gospels. The third part will cover texts that are parallel in three Gospels. And the fourth part will cover texts that are parallel in all four Gospels. For these Substack posts, part 1 will be a sample of the first part of the commentary, part 2 will be a sample of the second part, and so on it will go until it resets (part 5 will be a second sample of the first part on free-floating texts, and so on). By the end of the year, there will be three samples of each part of the larger commentary that I have not made available previously.

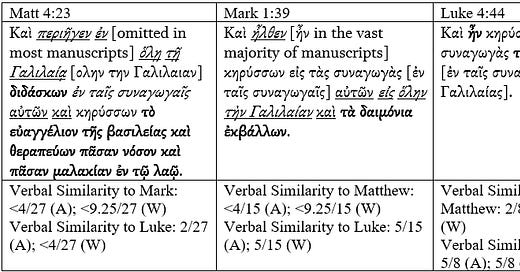

At the beginning of each of these parts, I will repeat my procedure for marking the tables of parallels. For all texts, plain font words are absolute similarities between texts, regardless of where they appear in word order and without repetition (if one word appears once in one text and twice in another, it is only counted once, and so on). Italics signify either a different form of the same word or a synonymous word paralleled in each text. Bold font signifies what is unique to each text. For texts with three parallels, single-underlined words signify elements shared between two of the three texts. The Greek is taken from NA28 and the similarity scores outlined below are based on this text. Brackets include variants attested in at least five Greek witnesses that make the text closer to parallels. Alternatively, brackets may feature text-critical notes on what the majority of texts include or lack.

For each text, I will give two scores of similarity to each of the other Gospels: one will be cases of absolute matching and the other will be cases of “weighted” matching, not counting variants (assigning a value of 1 to absolute matches, 0.75 to alternate forms of the same word and 0.5 to synonyms). There is no easy way to account for variation in word order in these similarity scores, thus my only solution to make note of these variations is to put a < symbol next to scores to signify that the verbal similarity is actually less than the calculated score would indicate because of the difference in word order where the wording is otherwise similar.

With all that tedium said, the parallel we address today is a comment on Jesus’s activity in synagogues paralleled at different places in Matt 4:23 // Mark 1:39 // Luke 4:44.

The preceding texts in Mark 1:35–38 and Luke 4:42–43 are only roughly parallel (as a later part of the commentary will cover, though they are functionally quite similar, these parallels have an absolute verbal similarity of less than 25%). But the equivalent in Matthew, which is less similar to the other Gospels, immediately follows the calling of the disciples in Galilee. Moreover, what follows each text greatly differs in each Gospel.

The common elements in all three, besides the extremely common opening conjunction, are the reference to going in(to) the synagogues proclaiming. Only Matthew provides a hint of the content of the proclamation, though the context of each Gospel obviously supplies context for inferring what he proclaimed therein. The majority of manuscripts for Luke indicate a further common element in reference to Galilee, but the text used here says that the synagogues were in Judea. I will consider at another time the arguments for this being the original reading, but for now it seems that the reason for accepting the reading “Judea” attested in multiple transmission streams, though being from a distinct minority of manuscripts, as original would be because the predominant reading appears to be a correction or a perceived correction. Again, setting aside engaging with other scholars for now, it is intuitively more likely that reference to Galilee would be introduced as a correction than that “Judea” would be introduced later apropos of nothing. The perceived need for correction would come from the fact that the texts before and after this remark, at least when location information is given, take place in Galilee. It is something of a harsh transition to move from going about in the synagogues of Judea to saying that Jesus was by the Sea of Galilee (or Lake Gennesaret; Luke 5:1). As such, sometimes a broader understanding of “Judea” has been proffered.

Matthew and Luke do not share any features that are not also shared with Mark. But Luke follows Mark’s word order to the extent that they overlap, which is not surprising given how short Luke’s text is and how intuitive the word order is. Matthew and Mark share referring to “all of/the whole of” Galilee and a roughly synonymous verb for movement, though Matthew’s is more specific than Mark’s. Matthew’s verb is rare, as he uses it three times (4:23; 9:35; 23:15), but that also accounts for half the uses in the NT (Mark 6:6; Acts 13:11; 1 Cor 9:5). Given how rare and relatively insignificant this verb is, it would be a real stretch to call it a Mattheanism or some mark of Matthean redaction.

Nor can the additional elements of Matthew’s texts be clearly assigned to redaction, apart from deciding the relationship between the texts beforehand. After all, reference to “the good news” (εὐαγγέλιον) is more common in Mark (8x) than Matthew (4x), or even in all of Luke’s writings (where it appears twice in Acts 15:7; 20:24), but it does not appear in Mark’s parallel. Although Matthew does feature more references to the kingdom than any of the Gospels, his characteristic modifier “of heaven” is not present, and there are times when other Gospels feature it in parallel texts with Matthew where Matthew does not include it, whether in reference to the kingdom of God or not (Mark 3:24b; 6:23; 9:47; 10:15 // Luke 18:17; Mark 10:24; 12:34; 15:43 // Luke 23:51; Luke 9:11, 60; 12:32; 18:29; 19:11; 21:31; 22:18, 29–30).

However, it should be noted that the rest of Matthew’s text here is a matter of his design. The narrator remark here from “teaching in their synagogues” to “every infirmity” is identical to the summary remark in Matt 9:35, which is without parallel in the other Gospels. There is also a similar remark in 10:1, but this is largely paralleled by Luke 9:1 with the only significant difference also carried over from here being reference to “every infirmity” (πᾶσαν μαλακίαν). That noun is unique to Matthew in the NT, being used only in these three texts. This term was used in several places in the LXX/OG for referring to sickness, pain, or harm, mostly translating the Hebrew חלי (Gen 42:4; 44:29; Exod 23:25; Deut 7:15; 28:61; 2 Chr 6:29; 16:12; 21:15 [2x], 18–19; 24:25; Job 33:19; Isa 38:9; 53:3).

Likewise, the “plusses” in Mark are not exactly peculiar to him. Both the verb and the noun appear more frequently in the other Gospels. One could argue that the use of the periphrastic participle construction that is unique to Luke’s version—provided that one dismisses most manuscripts of Mark—could be seen as a redactional effect. This type of construction is more common in Luke than the other Synoptics combined (to say nothing of Acts), and there are several occasions besides this one where Luke uses a periphrastic participle where he does not have entire additional clauses compared to the other Synoptics (Luke 4:38; 5:18, 29; 6:43; 8:40; 17:35; 20:6; 22:69; 23:19, 53). But most of the other instances of unparalleled periphrastic participles are in unparalleled sentences in Luke, and there are also many cases where Matthew and/or Mark have periphrastic participles where the parallels in Luke have none (Matt 5:25; 10:30; 12:4; 19:22 // Mark 10:22; Matt 24:38; 27:33 // Mark 15:22; Matt 27:55 // Mark 15:40; Mark 2:6, 18; 13:25; 14:54; 15:7, 26, 43, 46). In short, this is unconvincing as a sign of redaction.

In this particular instance, there does not appear to be any indication of a direction of textual dependence here one way or the other. The similarities appear incidental and derive more from narration of common activities for Jesus than from any common text or common tradition used as a source.

Part 2: Matt 4:18–22 // Mark 1:16–20

Part 3: Matt 4:1–11 // Mark 1:12–13 // Luke 4:1–13

Part 4: Matt 3:1–17 // Mark 1:2–11 // Luke 3:1–9, 11–15, 21–22 // John 1:19–34

Part 5: Matt 7:28–29 // Mark 1:21–22 // Luke 4:31–32