(avg. read time: 11–22 mins.)

In the course of my doctoral program, especially in preparation for my comprehensive exams, a method I developed much greater interest in was textual criticism. I have one article published in this particular field, which I will talk about another time, but I am by no means someone thoroughly familiar with all of its history or the ins and outs of the methods developed within it. What I have used as a basis for this introduction is my own notes and reflections that I composed in preparation for my comprehensive exams. I offer my work here as something of potential value for others with burgeoning interest in NT scholarship and in textual criticism in particular.

Textual criticism involves the analysis of the manuscripts of a text for one or more of the following purposes: 1) establishing the earliest recoverable text (or “original” text, depending on who you ask) that is most likely in a given context; 2) concomitantly, evaluating the plausibility of competing readings of a text; 3) identifying the genealogy to which a given manuscript belongs as a way of explaining the grouping of variants; 4) discerning what a particular manuscript or family of manuscripts might convey about the history of the text and the communities that used them (this last purpose is peculiar to textual criticism of scriptural texts, as opposed to, e.g., textual criticism of Josephus). In all of these ways, textual criticism concerns variant readings and explanation of the same. It also draws upon a number of disciplines, including philology, the study of particular ancient languages, translation theory (particularly in the case of non-Greek versions), paleography, and even historical theology (in the case of the final purpose). The field in which it works includes manuscripts of several varieties across many centuries, including early papyri, codices (including uncials/majuscules [texts written entirely in capital letters] and minuscules), lectionary texts, and patristic quotations (which span almost the entirety of the NT). I am here mostly concerned with talking about NT textual criticism, but I will also have a post going further in-depth on OT textual criticism, since it involves certain idiosyncrasies compared to NT textual criticism.

History

Textual criticism as a practice has ancient roots. It was one of the practices of the librarians of Alexandria as they sought to preserve texts. Quintilian references it as a necessary activity in teaching a text by establishing a correct, agreed upon reading (Inst. or. 1.4.1–3, 5.5–6; 8.1). Among the early Christians, there is evidence of practicing textual criticism as early as Justin Martyr as he sifts through different readings of the OT (Dial. 120; 124). Origen engaged in the practice much more systematically; he produced his Hexapla for precisely such a reason. Jerome, patron saint of Bible scholars, likewise engaged in textual criticism to establish a Latin translation of the OT based on Hebrew, rather than simply using the Greek versions.

Textual criticism would continue to be practiced in pre-Renaissance scholarship by the likes of Nicholas of Lyra, Peter Lombard, Theodulf, Stephen Harding, and the Victorine school in general. Peter Comestor’s Historia scholastica, which was the most popular medieval biblical introduction for university students, as well as Franciscan and Dominican friars, included instruction on textual criticism (especially in terms of accounting for every possible variant as providing insight into the Scripture). Nicholas Manjacoria likewise composed rules for proper procedure in textual criticism. Dominican and Franciscan friars trained by these people, most famously Roger Bacon, in turn composed correctoria to list corrections of the Latin Vulgate. However, two major differences separate the attempts to establish the correct reading in medieval scholarship from similar efforts in Renaissance and post-Renaissance scholarship. First, medieval efforts were primarily directed at the OT, drawing from the Hebrew text (one of the results of frequent contact with Jews in Europe). Second, any textual criticism of the NT still meant working primarily with the Latin. Greek New Testament manuscripts would not become widely available to western European scholars until after the Fall of Byzantium and the consequent emigration of Greek scholars westward and the invention of the printing press around the same time.

From this new situation came the work of Desiderius Erasmus, who would change the state of NT textual criticism forever. He took a set of manuscripts most readily available at Basel (plus a manuscript of Revelation borrowed from Johann Reuchlin at Heidelberg), corrected them by reference to the Vulgate and the Fathers, and printed his own text. What he ultimately produced is what became known as the Textus Receptus. Robert Estienne relied primarily on this Greek text to produce his Greek New Testament with a critical apparatus. It was the fourth edition of this text that introduced biblical verse divisions.

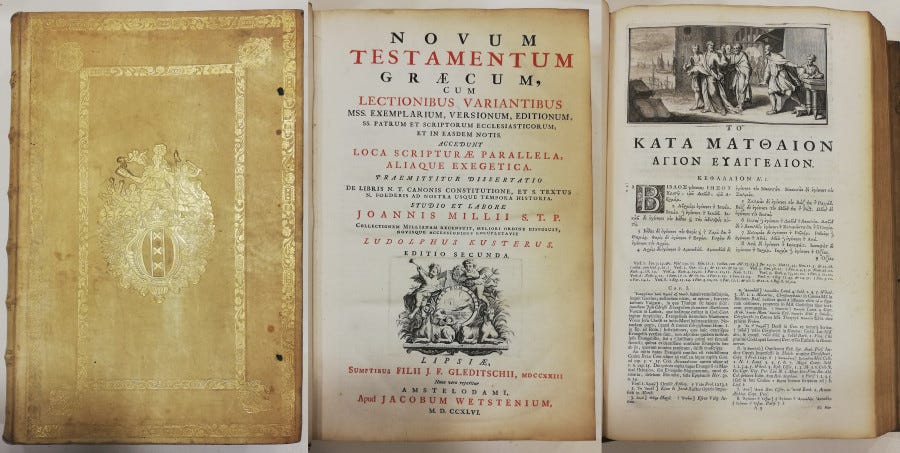

John Mill published his Novum Testamentum in 1707, which provided not only an edited Textus Receptus, but also a prolegomena, an appendix, and a critical apparatus that Mill had spent almost three whole decades developing. To create the apparatus with its lists of variants and textual comments, Mill utilized thirty printed editions and eighty-seven manuscripts. Additionally, Mill traced the history of the text to his own day. In that history, he gave particular weight to patristic quotations.

After John Mill, the three Johanns—Johann Bengel, Johann Wettstein, and Johann Griesbach—made additions to the textual apparatus, including confidence classifications. The various critical tools these scholars developed have had lasting impact to the critical editions of the NT used to this day. But they were still ultimately committed to the Textus Receptus as the “authoritative” edition of the NT in Greek.

It was not until approximately 1830 that biblical scholars in general began moving away from the Textus Receptus. Karl Lachmann was particularly influential in this regard in his aim to return to the fourth-century text. He was followed in this aim by, among others, Constantin von Tischendorf, B. F. Westcott, F. J. A. Hort, and Eberhard Nestle. Each of these scholars were also important in their own right in the development of NT textual criticism.

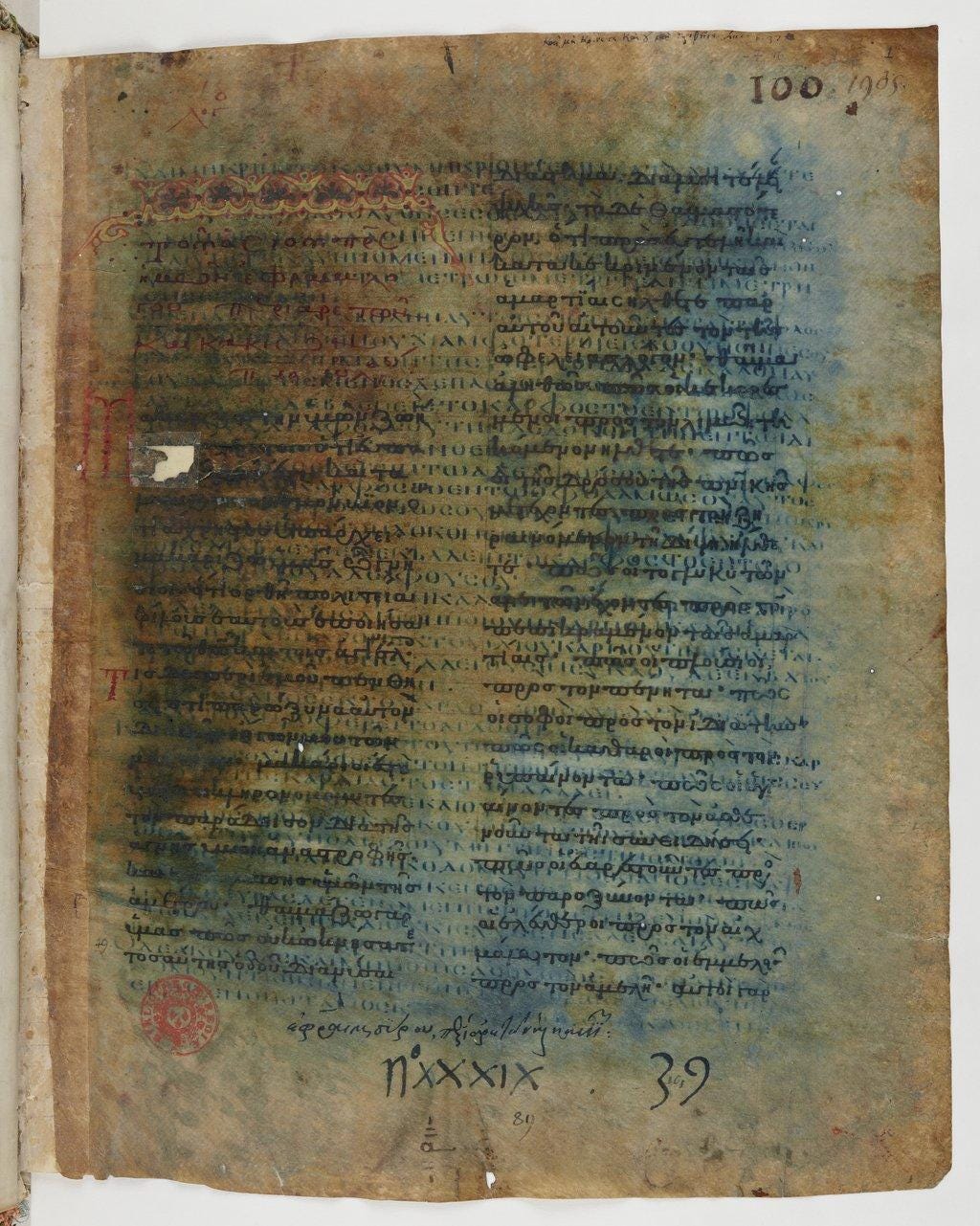

In the realm of textual criticism von Tischendorf is known especially for deciphering the palimpsest Codex Ephraemi Syri Rescriptus (C), bringing Codex Sinaiticus (א) to the attention of NT scholarship, and for his outstanding critical edition. The first distinction was no easy task, as one can see from the picture below, with text layered on top of text. As for א, he learned of it at St. Catherine’s Monastery at the foot of Mt. Sinai in Egypt. He recognized it as a fourth-century codex with a nearly complete NT with some parts of the OT. Through a long and complicated process, the controversial details of which need not detain us here, he brought this fascinating and immensely significant manuscript to the attention of Western NT scholarship for the first time in the mid-19th century. Finally, for his critical edition Novum Testamentum Graece, he consulted 64 uncials (with later editions being partial to א), one papyrus, and only a small fraction of the 3,000+ minuscules catalogued today. At the time, no one rivaled this breadth of work and his statements of the canons of textual criticism remain influential to this day, but that is something we will get to later.

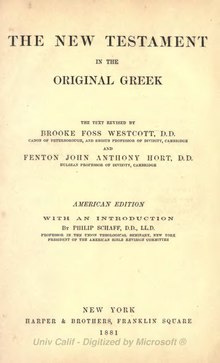

Whereas von Tischendorf was known for his association with Codex Sinaiticus, Westcott and Hort were known for their association with another fourth-century manuscript: Codex Vaticanus (B). However, this was not because they discovered it, but because they relied heavily on it in producing their critical edition of the NT, along with Sinaiticus. Both codices were regarded as representatives of the “Neutral Text,” having a common ancestry with Alexandrian texts (particularly as represented in Codex Alexandrinus [A]) but freer from corruption and closer to the original autographs. Where these two manuscripts agreed, Westcott and Hort took this to be a strong indication that they were as close as reasonably possible to the original text (and to this day, agreements between א and B, even when the majority of manuscripts say otherwise, tend to be bases for readings in recent critical editions). Their critical edition was also known for its dedication to the canon of textual criticism known as lectio brevior: the shorter reading is most likely to be earlier. We will get into the problems with this canon later, but for now it is enough to note that the importance given to this canon fits with more widespread assumptions about historical and textual developments in their era (which often continue today): the shorter and simpler was earlier while the longer and more complex was later.

Eberhard Nestle is known for initiating what would become the basis of the Novum Testamentum Graece that is now known as “Nestle-Aland” (currently in its 28th edition). Nestle formed his critical edition out of comparing the editions of Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, R. F. Weynmouth, and Bernhard Weiss. His son, Erwin, added significantly to the textual apparatus of this text from his research in the Greek manuscripts, early versions, and patristic citations. As thousands more Greek manuscripts have become more widely available, the later editions of Nestle-Aland and the companion volume of the Greek New Testament from the United Bible Societies (UBS) have produced editions that have taken account of more of the history of textual transmission, although neither of them are truly comprehensive.

One other figure of the late 19th and early 20th century is worth noting for how he negatively formed a major emphasis of textual criticism today. Hermann von Soden believed there were basically three recensions of the NT available in the 4th century, on the basis of which he reconstructed a hypothetical text that he claimed all the earlier Church Fathers used. One of the major problems with this idea is that it cannot explain how the fourth-century codices can feature such a variety of quality or textual lineage as they do in different parts of the NT. B is regarded as one of the highest quality manuscripts available and one of the best representatives of the Alexandrian text-type, but not in the Pauline epistles, where it has Western elements. א is also a prime representative of the Alexandrian text-type, especially in the Gospels, but it resembles the Western text in John 1:1–8:38 and many of the corrections made to it represent the Byzantine text-type. Yet, unlike Vaticanus, it retains a higher quality of text in the Pauline epistles. A has a Byzantine text-type in the Gospels and an Alexandrian text-type (with some mixture of Western readings) throughout the rest of the NT, including what many regard as the best text of Revelation.

To account for the flaws in von Soden’s reasoning, while maintaining the emphasis on identifying which texts are related to which, much attention in textual criticism has been given to collating texts in a genealogical fashion. One notable method, exemplified by Ernest Colwell, Paul McReynolds, Frederik Wisse, and later Eldon Jay Epp, is the “Claremont Profile Method.” The Textus Receptus, which largely represents the Byzantine/Majority text, is used as the collation base. In this method, variation units that agree more than 70% in their variants compared to the collation base belong to a particular family. Greater degrees of agreement can then support a closer genealogical relationship among manuscripts.

However, another, more popular method of categorizing texts in this fashion has come from Kurt and Barbara Aland. Theirs is a more simplified scheme that divides text into five categories. They have established these categories through “test-passages” that are decisive for identifying textual groupings and relationships. Category I texts are what they consider to be the highest quality texts, representing the Alexandrian text-type. Category II texts are texts they consider to be of high quality, albeit with the presence of some alien influence, particularly from the Byzantine text-type. Category III texts are generally considered independent and difficult to categorize as belonging to any particular text-type or text family. Category IV texts represent the Western text, the prime exemplar of which is Codex Bezae (D). Category V texts are the ones they assign the least value to as representing the Byzantine text-type of the majority of manuscripts. These are the majority of manuscripts because they typically come from Byzantium, where there was a greater stability for a longer time than anywhere else that led to a greater (though hardly perfect) standardization in producing Greek NT manuscripts.

Before I conclude this survey on history, two other facets of the landscape of textual criticism are worth noting. One, not everyone has agreed with the preference given to Alexandrian texts over Byzantine texts. The Majority Text Society (which produced a text published by Zane C. Hodges and Arthur L. Farstad) favored the originality of the Majority Text. Others, like Maurice Robinson, prefer to speak in terms of “Byzantine Priority,” meaning that any theory of textual transmission must account for the Byzantine text-type, rather than appealing to a hypothetical text that is not extant anywhere. As opposed to the approaches of “thoroughgoing eclecticism” (which assumes that the earliest and best readings are scattered throughout the textual record and can be determined by the use of a variety of text-critical canons, particularly internal criteria) and “reasoned eclecticism” (which selects certain manuscripts as being “the best manuscripts” that form the basis from which we can determine the earliest recoverable text by applying the text-critical canons), the Majority Text Society represents a documentary approach, while the Byzantine Priority approach represents a modified version. Robinson’s theory interestingly accounts for how the Byzantine text-type emerged as the result of a refined process of Christian communities sharing their manuscripts, comparing notes, and arriving at a consensus. I do not evaluate these different approaches here, but I want to make others aware that the landscape of today is by no means straightforward.

Two, a more comprehensive profile of textual variants and the genealogical relationships between them has officially been taken up by the Editio Critica Maior. The last time I checked, it was expected to be completed by 2030, but I imagine recent events have pushed this date out further. But it has thus far completed projects on the Catholic Epistles and the Book of Acts.

Canons of Textual Criticism

In terms of judging between variants and explaining how those variants arose, textual critics have devised a number of tests for the readings, mostly working from some or all of the following assumptions:

In terms of the original (or at least, earliest recoverable) reading, only one can be original and textual difficulties cannot be solved by conjecturing variants with no attestation.

The original/earliest recoverable reading is the one that best satisfies either external criteria, internal criteria, or a balance of both.

The genealogical principle is crucial in this regard in contributing to the explanation of how certain readings arose. Variants thus must be considered in the context of tradition.

Pride of place is given to the Greek manuscripts with the patristic quotations and other versions (mostly in Latin, but also in Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Gothic, Ethiopic, and Slavonic) being supplemental. A reading only attested in non-Greek manuscripts would generally not be preferred over one that is present in Greek manuscripts.

Generally, manuscripts are weighed, not counted. Even in Byzantine Priority, the argument appeals to a greater quality of Byzantine manuscripts than is generally acknowledged, not simply the fact that the majority of manuscripts favor it.

External criteria for analyzing readings include the following:

Age of manuscript (determined primarily by paleography)

Quality of manuscript (this is particularly important to categorizations like the Alands use)

Geographical distribution (Is the reading widespread or localized to, e.g., Rome?)

Number of manuscripts

Internal criteria for analyzing readings include the following:

The reading that best explains other variants is to be preferred.

The more difficult reading (lectio difficilior) is to be preferred, since it is, prima facie, more likely that scribes would make readings easier rather than more difficult.

The shorter reading (lectio brevior) is to be preferred, since it is, prima facie, more likely that scribes would expand texts and combine readings than shorten a text.

The reading more in line with the author’s style and theology is to be preferred. Another version of this criteria is that the reading more in line with the immediate context is to be preferred.

In the particular case of the Synoptic Gospels, the reading that is not harmonized or is less parallel is to be preferred, since it is, prima facie, more likely that scribes would harmonize similar texts from each Gospel than that they would create difference.

It is worth noting, however, that almost none of these criteria are absolute. Concerning the external criteria, the oldest manuscripts, though closer in time to the autographs, are not always the best; in fact, papyri like P46 and P66 contain a number of spelling errors that gave rise to many others that copied from them, not to mention other questionable variants. Quality judgments must always be tempered based on the specific manuscript; as noted above, Alexandrinus is said to be of lower quality in the Gospels, Vaticanus is said to be of lower quality in Paul, and Sinaiticus demonstrates a mixed lineage outside of the Gospels. (And of course, some of these quality judgments may be realigned according to judgments based on further study of what family they belong to.) Geographic distribution is helpful if the production centers of these manuscripts operated independently, but even then, some scribal groups operated according to higher standards than others. Number is of course the weakest of the criteria and nothing more needs to be said. It helps to have a census of witnesses for a reading, but it is by no means decisive.

Concerning the internal criteria, the principle of the difficult reading was once especially influential (as in Bengel, Griesbach, and Westcott-Hort), but its weaknesses have become more obvious over time. While scribes may have a tendency to smooth out difficult readings, sometimes a reading is difficult precisely because it does not make sense in the context and thus should not be preferred. This supposition about scribal tendencies, while prima facie probable, does not always apply, as there are several cases where what is supposed to be the easier reading is in a distinct minority of manuscripts. Furthermore, as I will show in the example of my own work, sometimes what is described as the more difficult reading may be based on a misunderstanding of how the reading came about and thus whether it can properly be considered more difficult.

The principle of the shorter reading makes sense, as scribes may add marginal notes, as well as their own impressions of what should be there syntactically or theologically, which are then sometimes added into the text proper. However, readings may be shorter because of accidental omissions (even entire lines could be omitted if two proximate lines ended the same way). Or they may be shorter as a way of correcting grammar from what was perceived as an “overly full” grammatical construction. Or, in the case of the Western and Eastern traditions of Acts, the shorter reading may simply be a different edition. In general, it is by no means given that developments simply happen from simpler to more complex. Sometimes, there may be reasons for simplifying what was once more complex.

The principle of context and style makes sense, because scribes may substitute similar words based on stylistic preferences of themselves or the time in which they write. But in some cases, we simply do not have enough text to be able to make strong pronouncements of an author’s style when a different term or phrase appears, and sometimes we overestimate how different prepositional constructions might be for the purpose of an author’s theology. Furthermore, as I also discuss in my own work, this sense of contextual fit can at times be based on misreading what the variant is actually saying.

The Gospel principle also makes sense in a way, as scribes and teachers of the Gospels (notably, Tatian) are all too keen to harmonize texts. But even this principle cannot be used by itself, lest we operate on the assumption that only texts that produce Synoptic Gospels as different as possible are to be preferred. Furthermore, if scribes did engage in harmonizing, we cannot assume it was all in one particular way. If we go by citations alone, the Gospel according to Matthew seems to have been the most popular of the Gospels to use in the early church, but it is by no means clear that harmonized readings are always attempting to align texts from Mark and Luke to Matthew, or if the harmonization went in another direction, or if the divergent reading was a deviation from a case where the Synoptics originally agreed on a textual level.

The only criterion that survives completely intact is the principle of best explanation. The earliest recoverable reading is the one that can best explain how other variants arose. Such explanation should further satisfy the criteria of best explanation, as I have outlined in my own work of background plausibility, explanatory scope, explanatory power, simplicity/parsimony, and illumination.

Key Findings and Key Issues in the NT for Textual Criticism

One group of key findings by textual criticism has been the cataloging and categorization of scribal or reader errors. That is, where scribes do not introduce intentional alterations for harmonization, grammatical improvement, syntactical improvement through transposition, clarification, or so on, there are a number of unintentional errors, including:

Interchange of letters, particularly vowels, due to having the same sound (homophony). The work of Chrys Caragounis is especially helpful here.

Haplography (omitting letters or words)

Dittography (doubling letters or words)

Homoioteleuton (two or more words, perhaps even an entire line, are skipped because words have the same ending)

Incorrectly separating words (since the texts were written in scriptio continua)

The Alands have compared numerous critical editions including Nestle-Aland, von Tischendorf, Westcott-Hort, and many others. Between all of these editions and the apparatuses therein, the Alands have found that, apart from simple orthographical differences, 4,999 out of 7,947 (or 62.9%) verses in the NT are variant-free. But this basic figure includes a range from 306 out of 678 (45.1%) verses in Mark to 92 out of 113 (81.4%) verses in 1 Timothy. In between these extremes, five books of the NT have between 50% and 60% variant-free verses (the other Gospels plus 2 Peter and Revelation), five books have between 60% and 70% variant-free verses (Acts, 1 Thessalonians, James, 1 Peter, and 2 John), and the majority have 70% or more variant-free verses.1 We have already seen reasons why the Gospels are on the lower end of this range. As for 2 Peter and Revelation, these books do not have nearly as many manuscripts containing them and because of the difficult grammar in both, one reason for the higher amount of variation is due to grammatical corrections or sometimes lexical variation. But in general, this is a remarkable degree of consistency.

Likewise, textual critics have demonstrated an even more remarkable degree of textual stability for the number, linguistic variety, geographical spread, and extensive textual history of the manuscripts. K. Martin Heide calculated the overall stability of each book as ranging from 89 to 98%, with the overall stability at 92.6%.2 In general, Michael Holmes has noted, especially in the cases of the Gospels and Acts, that we have macro-level stability (remarkable textual sameness of episodic content, narrative structure, and arrangement) and micro-level fluidity (words, phrases, and verses, rather than, generally, whole paragraphs or pages).3

Still, while the variations between texts are small, in some cases the differences involve much larger bodies of texts, and these remain key issues for analysis and discussion in NT textual criticism. In the case of omitting large bodies of texts, such a factor is not in itself decisive for the case of whether or not a text was part of the earliest transmitted version of the book. For example, P46, despite being an early papyrus, features some significant textual problems, such as its omission of Rom 16. Unlike the major cases noted below, as well as several stray verses noted in most of our Bibles today, the case against this omission is generally regarded as too overwhelming to take this omission seriously enough to print Rom 16 “with asterisks.” [Update (8/18/22): After looking into this suggestion, which I first came across from Raymond Brown noting the views of other scholars, I realized that the notes I based these comments on did not sufficiently grasp the complexity of the issues here. It is not that P46 itself omits Rom 16, but since it adds the doxology of 16:25–27 to the end of 15:33, it has been thought by some scholars (such as T. W. Manson in his article “St. Paul’s Letter to the Romans—and Others” and the scholars Karl Paul Donfried interacts with in his article “A Short Note on Romans 16”) that this manuscript attests to an early manuscript that only featured the first fifteen chapters of Romans. Rather than simply editing my text to accommodate, I thought the issue of misunderstanding was great enough here to warrant a clarifying update. There has, of course, also been significant debate about Rom 16:25–27 based on its different placement, and even of ch. 16, but it was inaccurate for me to say that P46 lacked the chapter as a whole.]

Most famously, two texts still printed in modern Bibles but “with asterisks” are John 7:53–8:11 and Mark 16:9–20, because some of the earliest texts are either lacking them (in the case of Mark) or the textual history is decidedly more complicated (in the case of John). I aim to engage the ending of Mark in much more detail at another time. [Update (5/3/23): I have engaged with the debates about the ending of Mark here, and I am one of the distinct minority that favors the authenticity of the last twelve verses.] As for the story of the woman caught in adultery, most manuscripts that feature it include it where it is, in some manuscripts it is included where it is with asterisks or obeli, in a couple cases it is included after John 21:25, and in one case each it is included after Luke 21:38 and John 7:36. But some manuscripts, including multiple versions, omit it altogether. Such a free-floating story indicates that it was important in the early church, and it may well tell a story of Jesus that circulated early. But if it was in this location from the start, it is curious that it should end up in so many different locations, albeit in minority witnesses. But exploring this issue and its cause(s), as well as if the majority testimony to its presence and placement is true, are beyond the scope of an introduction such as this.

Another case in which textual criticism puts at stake a larger body of text is in the case of the “Western text” of Acts. In this case, we are not dealing with one large body that appears in some manuscripts but not in others, but several instances of consistent additions in one tradition and not another. Moreover, these additions are extended versions of narrative episodes, but not a rearrangement of them, nor does the Eastern text present any excisions of the same. In this case, the Western text typically matches the style, and it does not present obvious cases of theologically motivated emendations by copyists. As such, some have proposed a two-edition theory for Acts, which can take one of the following forms. 1) Luke wrote both, either with the second one being the more polished Eastern text or the more expanded Western text. 2) A scribe glossed the Eastern text with notes from Luke to produce the Western text. 3) The Western was the original edition while the Eastern text was produced later for wider circulation. 4) The Western text is the earliest recoverable text (but not the original) while another author produced the Eastern text by revising the Western text in light of his access to the original text. I hope to examine these various options another time, but what is noteworthy for now is the role that textual criticism plays in bringing this problem to light and in helping to adjudicate between the different historical reconstructions of what happened to this text.

Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland, The Text of the New Testament: An Introduction to the Critical Editions and to the Theory and Practice of Modern Textual Criticism, 2nd ed., trans. Errol F. Rhodes (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1989), 29.

K. Martin Heide, “Assessing the Stability of the Transmitted Texts of the New Testament and the Shepherd of Hermas,” in The Reliability of the New Testament: Bart D. Ehrman and Daniel B. Wallace in Dialogue, ed. Robert B. Stewart (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2011), 125–60 (esp. 138).

Michael W. Holmes, “From ‘Original Text’ to ‘Initial Text’: The Traditional Goal of New Testament Textual Criticism in Discussion,” in The Text of the New Testament in Contemporary Research: Essays on the Status Quaestionis, 2nd ed., ed. Bart D. Ehrman and Michael W. Holmes (Leiden: Brill, 2013), 674.