Resurrection in the OT, Part 8

Ezekiel 37:1–14

(avg. read time: 8–16 mins.)

Of all our resurrection texts, Ezek 37:1–14 is by far the most vivid. It portrays a step-by-step resurrection process as a process of new creation. If there was ever any doubt that literal resurrection is a bodily reality, and that even where it is used metaphorically it draws its forcefulness from the source image of bodily resurrection, this passage should dispel such doubt. Likewise, as noted at multiple junctures throughout this series, the effectiveness of the imagery relies on the belief that God can raise the dead, which is upheld by multiple factors in biblical theology up to this point (see part 1 for more on the foundations, as well as for a hub linking to the rest of the series). One can scarcely imagine Ezekiel rebuffing later interpreters who would take this text literally with, “That was only a metaphor, I surely do not expect God to raise the dead.”

This account of the process is then followed by an explanation that shows how this text is the exemplar of the paradigm noted at multiple points of correlating life with following the covenant with God (cf. Lev 26:9–13; Deut 28:1–14; 30:19–20; Pss 1; 119), death with exile, and resurrection with return/restoration. In this context resurrection imagery is a fitting metaphor combined with the severe separation and disintegration of relationship with God that the state of exile, subjugation, and dispersion/disintegration itself signifies. The fittingness of this metaphor is well established from the story of Genesis, in which Adam and Eve’s exile from the garden and the special relationship with God thereby entailed is tied to the condition of death.1 Given what has been noted previously about the significance of occupying the promised land, exile was not an arbitrary punishment for unfaithfulness; it was an organic and effective punishment proclaiming the brokenness of the covenant and thus the end of the covenantal way of and to life (Lev 26:33–39; Deut 28:63–68; 29:22–28; 30:19–20). By the same token, restoration of the covenant and return from exile would mean return to life (Lev 26:40–45; Deut 30:1–10; 32:15–42), or resurrection, as Ezekiel describes it.2

I have not done a census to confirm this, but it appears that this text is the most widely appealed to of all the resurrection texts in the OT. Many early church accounts of resurrection, including in terms of it fulfilling Scripture, make appeal to this text (e.g., Did. apost. 20; Tertullian, Res. 29–31; Origen, Comm. Jo. 10.20; Hom. Lev. 7.2; Cyprian, Test. 3.58; Methodius of Olympus, Res. 1.23; 2.21; 3.9 Gregory of Nyssa, Anim. Res. [NPNF[2] 5:460]; Jerome, Jo. Hier. 29; Epiphanius, Anc. 99; Pan. 64; Cyril of Jerusalem, Cat. Lect. 18). It was also a key resurrection text for the rabbis (y. Šabb. 1.3; y. Ta‘an. 2b; Gen. Rab. 13.6; 14.5; Lev. Rab. 14.9; Deut. Rab. 7.6; Sipre Deut. 306.35; Midr. Tannaim Deut 32:39). Before either of these groups appealed to it for discussing literal resurrection, it was used for literal reference to resurrection at least as early as the writing of 4QpsEzek[a]/4Q385, a century or two before Christ. Other Second Temple texts, whether or not relying on Ezek 37, used the same association of resurrection with return and restoration of the people (2 Macc 7:32–38; 1 En. 62:15–16; 90:33; 2 Bar. 29:8; 75:7–8; T.Dan 5:8–9; T.Benj. 10:11; Liv. Pro. 2:15). The Amidah also connects these concerns through the Second and Tenth Benedictions. In other cases still, the resonance comes more from the description of resurrection as an act of re-creation and re-formation of humans, as in Sib. Or. 4.181–182 or in some rabbinic texts (b. Sanh. 90b; 91b; Gen. Rab. 8.1; 14.2–5).

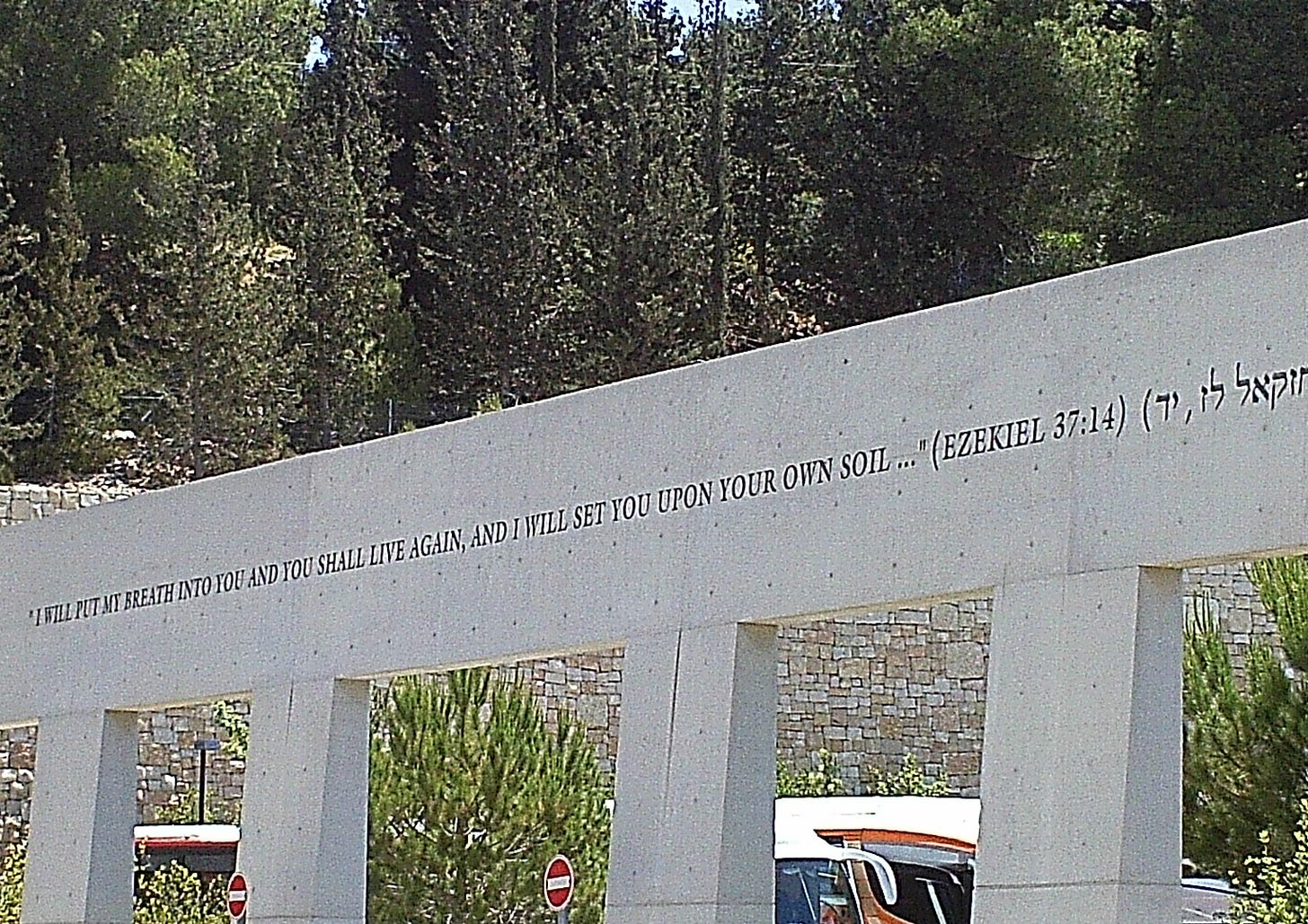

Even beyond the literary realm, one can see the impact of Ezek 37 as a vivid portrayal of resurrection. I mention here only two prominent examples. First, along with a depiction of Elijah raising the widow’s son, one of the murals at the Dura-Europos synagogue depicts this scene (as shown in figures 12, 13, and 15 here). (This mural is also connected with a certain tradition of reading Zech 14 with its reference to the splitting of the Mount of Olives as being related to the resurrection of the dead. On that text, see here). Second, at the entrance to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial in Jerusalem, part of the closing verse of this scene is displayed on an arch. Here is a picture I took of it in 2011.

But now we must turn to the text itself to see what it can show us about its use of resurrection language. Ezekiel 37:1–14 belongs in the context of Ezek 34–48, the section devoted to oracles of comfort and assurance of Israel’s deliverance from exile and restoration. This section contrasts with 1–24, which consisted mostly of judgment oracles against Israel (with a few passages of comfort, such as 11:14–25) and with 25–33, which proclaimed God’s judgment against the nations and the climactic judgment against Jerusalem itself.

In 34 and 36, there is the promise of renewal of the covenant with Israel and of the covenant partners in Israel themselves. In 35 and 38–39, there are focuses on defeat of the enemies of Israel and the security of the people in the promised land as a result. In 40–48, there is the promise of the return and renewal of the destroyed temple along with the renewal of Jerusalem and the promised land as a whole (also see 36).

More immediately, the passage follows the promises of ch. 36 for the renewal and fruitfulness of Israel—the people and the land—as well as their return from exile to be faithful to the covenant by the power of God. Indeed, the presence and action of the Spirit of God in this work of renewal is carried over from ch. 36 (vv. 26–27), albeit now with the Spirit engaging in the work of resurrection in parallel to the renewal of the covenantal people in that chapter. 37:1–14 functions as an extension and exposition on the aspects of renewal and return through the image of resurrection. It also anticipates 37:15–28 and its promises of reconstitution of Israel with the renewed reign of David over the people in their proper land forever.

This text is also occupied with the portrayal of the power of God’s word to the point of describing resurrection as an act of new creation by God’s word. The whole passage of God speaking through Ezekiel displays the power of God’s word as God speaks and whatever he speaks happens. God promises that the bones will be covered with living bodies once again and they are. God calls for the Spirit/breath to enter into the bodies to make them live and the Spirit/breath does so. These points provide the reassurance that Israel had known throughout her history about God’s promises, but no statement puts as much of a punctuation mark on the point as v. 14, where God simply declares, “I have spoken and I will do it.”

Such power and initiative are placed on God’s side of this relationship because of the utter hopelessness of Israel’s situation. Ezekiel goes out of his way to emphasize the extreme degree of deadness of these bones. Death itself has a sense of finality and irreversibility (apart from resurrection), but Ezekiel’s piling on of descriptions conveys the point that these bones are really, really dead. They are dead, deceased, demised, expired, no more, bereft of life, and wasted away. The Israelites are not simply dead corpses; they are slain corpses (that is, they have had their lives forcibly taken, v. 9). They are not simply slain corpses; they are shameful and cursed unburied corpses (vv. 1–2). They are not simply shameful and cursed unburied corpses; they are now skeletons. They are not simply skeletons; they are indiscriminate piles of bones (vv. 1–5, 11). They are not simply indiscriminate piles of bones; they are extremely dry bones (v. 2), presumably on the verge of turning back to dust. When God poses the question to Ezekiel, “Can these bones come back to life?” the answer seems obvious. By themselves, they cannot. Thus, there is a further implied question: Will God make them live? As far as the Israelites are concerned, as conveyed in v. 11, the answer is once again, “No.”

Another element of severity to this condition is not simply the aspect of death, but the contemptible, impure nature of this fate. The curse of being an unburied corpse was perhaps the gravest of all covenant curses in the ancient Near East (ANE) and in the OT in particular.3 Unburied bodies are the ultimate symbol of uncleanness/impurity, as they have no place among either the living—whose world their presence intrudes upon—or among the rest of the dead—where they would belong if properly buried. It is thus a most fitting image of being cursed.

This cursed condition applies to the people in exile, apparently sometime after the destruction of Jerusalem and its temple, the ultimate expression of God’s wrath against the people. The exiles were now cut off from the promised land with no anticipation of going back and with seemingly nothing to go back to. Their identity was gone. They had been the covenantal people of the God who brought them up out of Egypt. But then all the signs of the covenant were gone. They were not faithful to the covenant and perished from a lack of knowledge of the covenantal God. Their promised land was no longer theirs. They were cut off from their fellow Israelites. The temple, the symbolic house of God’s presence among his people, was abandoned and destroyed. With the destruction of the temple came the cessation of sacrifices and the apparent inability to be cleansed of sins (hence the fact that Israel now consists of unclean, unburied bones). The destruction of the temple also meant the end of their sacred festivals in which they reiterated their story as a people. Indeed, this event called into question the whole story of the people. The firm establishment of the temple had become the consolidation and climax of the story. But with its destruction and the apparent abandonment of the people by their God, the people began believing that it signaled the death of who they were and that it rendered meaningless their story as a whole. A people without a future can cease to care about a past that leads to nothing. Such is the lot of those who regard themselves as consummately cursed.

But what is notable about Ezekiel and its larger OT context is that the OT is the only collection of texts in the ANE that envisions the possibility of reversing a curse, especially one described this severely (cf. Deut 30:3–7).4 This is only possible because of the involvement of the God who raises the dead. The fact that Ezekiel turns the question God asks him back to God indicates his humble ignorance and his recognition that the question is ultimately whether God will (rather than can) raise these bones to life again.

When God directs Ezekiel to prophesy to the bones, it is notable that there is no exhortation to Israel here; there is simply the promise of “resurrection.” Ezekiel 36:26–27 implies that the presence of the Spirit entails faithfulness to the covenant, but even this renewal happens by the impetus of God and not by exhorted action. God is taking the initiative here for a people that is deader than dead. It is fascinating that in the interpretation provided in v. 12 that God is willing to call them “my people” (a covenantal affirmation), even though they are not currently defining themselves by their faithfulness to the covenant in any way. They must relearn what it means to be God’s people. To do that, they must learn about who God is, as the end of v. 6 takes up.

What we see at the end of v. 6, as well as in the interpretation provided in vv. 13–14 is a point that Ezekiel is uniquely emphatic about. Some variation of the statement “you/they shall know that I am the Lord” appears sixty-two times in Ezekiel (here in vv. 6 and 13), more than all other books of the OT (or the Bible as a whole, for that matter) combined. Another phrase, “you/they shall know that I, the Lord…” appears eight times, once here in v. 14. Perhaps an underlying center of gravity connecting this scene with the rest of the book is the question of the identity of God and the identity of the people of Israel in connection. The Israelites were perishing due to unfaithfulness to the covenant—thus, a lack of love for God and for people—and lack of knowledge of the God with whom they were in covenant. Through both wrath (the usual action connected to “you will know”) and restoration, God is directing them back to himself. He has killed, but he will also make alive. And as in other resurrection texts, the fact that this is a revelatory action that enables people to recognize God as the Lord shows how resurrection is an identifying/characteristic action of this God.

Beginning in v. 7, we see a typical scene from the OT, wherein the declaration of God is given and, in the subsequent passage, each detail comes to pass in fulfillment of God’s word. God’s word is truly effective in overcoming all obstacles to fulfillment and nothing can ultimately gainsay his declaration. The anatomical knowledge here of moving up from bones to sinews to flesh (or meat) to skin may stem from Ezekiel’s priestly background since the priests would be the ones who cut up the animal sacrifices. But this reconstitution is only the first act. For true reinvigoration, there must be a re-creation with the Spirit giving life as God had given the breath of life to the inanimate dust in Gen 2:7.

As in Gen 2:7, God first forms the bodies (though not described as directly as in Gen 2) and then breathes into the bodies the breath/Spirit of life. This sequence of events not only illustrates the power of God; it illustrates the difficulty of the task. The pieces cannot simply be brought back together and made to live again. Now God must give “my Spirit” (v. 14) for the people to live their eschatological life, their everlasting life. And indeed, while the scene of resurrection described here is like no other in the OT in its level of vivid detail, we see here a verb that has been applied many times where it refers to resurrection when the verb comes after death: חיה (vv. 9–10). We also see in v. 10 another verb that will be used again in Dan 12:13 to refer to standing again after death: עמד. This verb overlaps with קום, another verb we have seen applied to resurrection in contexts of death.

The whole passage concerns a reversal of conditions, but it becomes especially acute in the last four verses. What the people say about themselves in verse 11 is essentially a funeral dirge (in Hebrew, the three clauses are two words each and all of the clauses rhyme with each other). But with the promise of God being that they he will raise them from out of their graves—now changing the metaphor from the mass open grave to that of individual ones— and settle them in their proper land, the funeral dirge should be replaced by a panegyric of reconciliation. The bones live again, hope endures by the promise of God, and they are no longer cut off, but are in their proper place.

We thus also see more of the larger eschatological context for eschatological resurrection as, given the context, this is one of our clearest cases of an eschatological setting for resurrection thus far. It is not enough simply to restore the status quo. A greater transformation of the situation and setting is needed. Exile, subjugation, and dispersion/disintegration must be addressed with God’s action of return, reign, and reunion.5 Later, this vision will be brought to completion with the renewal of the temple and land in chs. 40–48. But more immediately in vv. 15–28, this vision of resurrection is complemented by the reunion of the twelve tribes (referred to by the synecdoche of Ephraim and Judah) under the reign of God’s promised Davidic king. Such promises signal the fulfillment of hopes stated elsewhere in the OT (Isa 9:1–7; 11; 55:1–5; Jer 23:5–8; 30:1–3, 18–22; 33:14–26; Ezek 34:23–31; Hos 3:4–5; Mic 5:2–15) and that would continue to be articulated in Second Temple literature (T.Sim. 7:2–3; T.Jud. 24; T.Naph. 8:2–3; Pss. Sol. 17:21–46; 4QcommGen A V, 1–4; 4Q504 1–2 IV, 5–8; 4QpIsa[a] III, 11–24; 4QFlor 1 I, 7–13).

For more on the sense of death in Gen 2–3, see R. W. L. Moberly, “Did the Serpent Get It Right?” JTS ns 39 (1988): 1–27; Moberly, “Did the Interpreters Get it Right? Genesis 2–3 Reconsidered,” JTS ns 59 (2008): 22–40.

For more on these interconnected stories of as Covenant-Sin-Exile-Restoration and Creation-Sin-Exile-Restoration, see Roy E. Ciampa, “The History of Redemption,” in Central Themes in Biblical Theology: Mapping Unity in Diversity, ed. Scott J. Hafemann and Paul R. House (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007), 254–308.

Brian Neil Peterson, Ezekiel in Context: Ezekiel’s Message Understood in Its Historical and Ancient Near Eastern Mythological Motifs, PTMS 182, ed. K. C. Hanson, et al. (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2012), 232–47.

Peterson, Ezekiel, 249–53.

For other texts dealing with these same concerns, see Isa 11:11–16; 27:12–13; 35:8–10; 40:1–2; 43:5–7; 44:26–28; 48:20–21; 49:8–26; 54; 56:8; 58:9b–14; 60; 61; 63:8–64:12; Jer 3:15–18; 11:4–5; 12:14–17; 16:14–15; 23:3–8; 24:4–7; 29:10–14; 30:3, 8–11, 17–22; 31; 32:37–33:26; 50:4–5, 19–20, 33–34; 51:10; Ezek 11:15–20; 16:59–63; 17:22–24; 20:33–44; 28:24–26; 34:11–31; 36; 37; 39:25–29; Dan 9:15–19, 24–27; 11:1–12:13; Hos 1:10–11; 11:1–11; 14; Amos 9:11–15; Mic 2:12–13; 4; 5:2–9; 7:11–20; Nah 1:12–13, 15; 2:2; Zeph 3:14–20; Zech 1:16–21; 2:6–13; 3:6–10; 6:9–15; 8; 9:9–17; 10:6–12; 14:3–21; Tob 13:1–16; 14:4–7; Sir 36:10–13; 48:10; Bar 2:24–4:29; 4:36–37; 5:5–9; 2 Macc 1:27–29; 2:7–8, 17–18; 1 En. 90:28–29; Sib. Or. 3.282–294, 702–720; 4 Ezra 13:32–50; 2 Bar. 78; Apoc Abr 27; T.Iss. 6; T.Dan 5:8–9; T.Naph. 8:2–3; T.Ash. 7:8; T.Benj. 9:2; Jub. 1:15–18, 22–25; Liv. Pro. 3:5, 12, 17; 12:8; 14:1; 4 Bar. 3:14; 4:9; 6:24; 7:22–23; 8:3–11; Pss. Sol. 8:28; 9:1–2; 11; 17:26–32; 1QM I, 2–3; III, 13–14; V, 1–2; 1QLitPr/1Q34 1+2, 1–2; 4QapocrJosephb/4Q372 1, 13–20; 4Q504 1–2 VI, 10–14; 4QpapPrFêtesc/4Q509+4Q505 3 I, 3–4; 11QTa/11Q19 LIX, 5–21; Philo, Rewards 164–172.