(avg. read time: 42–84 mins.)

Introduction

On the assumption of the widely held claim that Mark 16:9–20 is a later, inauthentic (i.e., non-Markan) ending for the Gospel according to Mark, there is still a need for explaining the text and how it came to be. James A. Kelhoffer has offered the most robust version of a particularly influential hypothesis. According to him, “the LE’s author deliberately imitated the four NT evangelists’ writings…. The hypothesis that the LE’s author was an imitator of earlier traditions will thus be tested here. That is to say, the vast majority of 16:9–20 does not bear marks of this author’s own novel composition or style, but rather those of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.”1

Many authors have taken this claim and its supporting arguments for granted or as demonstrated.2 Unfortunately, they have not provided any sort of extensive analysis of the argument to show why it is forceful. Upon closer inspection, Kelhoffer’s case is logically suspect at a number of levels.

Since Kelhoffer assumes Mark 16:9–20 to be by an author other than Mark on the basis of arguments others have made (his is not an inductive case, and similarities to Mark are taken to be imitations rather than possible markers of Markan authorship), similarities lend themselves to his idea that it was written in the second century after all the Gospels. Other instances of similarity (and more substantial ones at that) with the other Gospels tend to lend themselves to the idea that they borrowed from Mark, but here it is reversed. Why is the switch in reasoning made here? Because this text was written in the second century, or so it is claimed.3 And so on the circle goes. Of course, as I have shown previously here and here, I am not one who is inclined to agree with the popular claim that this text is non-Markan.

There is also a frequent curious assumption informing his analysis of similarities. The best way I can think to describe this set of assumptions is that the texts of the Gospels plus Mark 16:9–20 function like an isolated thermodynamic system wherein similarities of wording or construction must be explained as either the novel composition of a non-Mark author or an attempt to imitate the Gospels. Nothing outside of this system can have an effect. Broader Greek fluency on Mark’s part, or even on the part of a supposed non-Markan author, cannot be the explanation if a similarity can be identified in Mark 1:1–16:8 or another Gospel. Only in the absence of such similarities is an alternative explanation allowed, which is simply that the non-Markan author came up with the linguistic item in question. Conversely, pursuant to the claim of non-Markan authorship, Mark’s Gospel itself is treated as an isolated thermodynamic system, so that if a word or specific kind of construction does not appear elsewhere in Mark, that simply means Mark could not have written it (examples below will show that this is not an exaggerated characterization).

In line with such assumptions, there is another consistent assumption that the source of knowledge of a thing is always textual. It cannot have come to the author (Mark or pseudo-Mark) in any other way. For example, Kelhoffer writes of the participles πορευθέντες and ἐξελθόντες, although they are forms of extremely common verbs in Greek (each appearing tens of thousands of times in texts in the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae), that “no extracanonical passage offers a more probable source for the LE than Matt 28:19 and Mark 6:12 do.”4 What was never considered in this context is if textual explanations for isolated terms like this was even necessary. Nor indeed is an appeal to oral transmission, even including the indirect influence of the written Gospels as they are read aloud in a communal setting, entertained because, as he says, “the correspondences between the LE and the NT Gospels are so striking that dependence upon written documents is the most likely explanation.”5 More specifically, he insists that the writer had access to copies that he used for the composition of Mark 16:9–20.6 Even mediation of similarities by memory of text is banished from consideration.7

Immediate Comparison

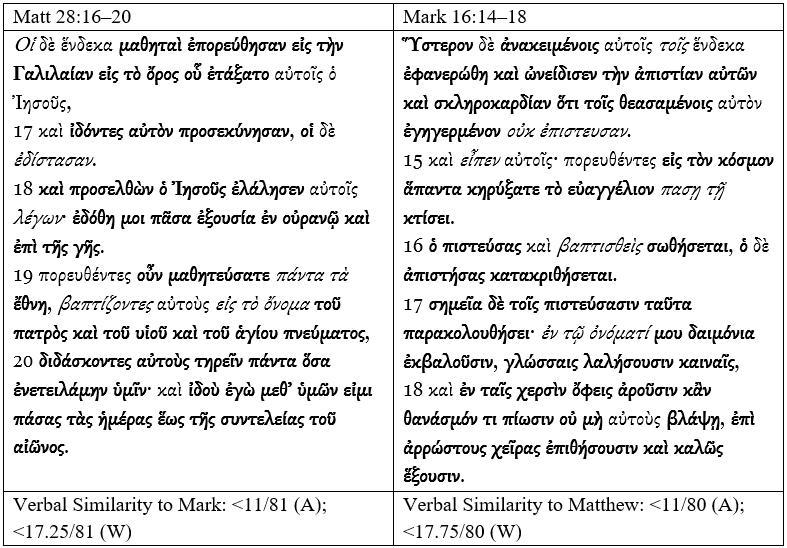

As a baseline for comparison, I provide the most direct parallels below, as well as the empty tomb narratives that precede the rest of the endings of the respective Gospels. With these charts I use, I must again give some guidance on how they are marked. For all texts, plain font words are absolute similarities between texts, italics signify either a different form of the same word or a synonymous word, and bold font signifies what is unique to each text. For text with two parallels, all these same rules apply. For texts with three parallels, single-underlined words signify elements shared between two texts. The same applies to texts with four parallels, but elements shared between three texts are doubled underlined. The first similarity score is based on absolute verbal similarity of identical wording, even when the similarities appear incidental. The second similarity is based on weighted verbal similarity, including scores of 0.75 for each word that is a different form of the same word in a parallel text and of 0.5 for each word that is a synonym for a word in a parallel text (again, this applies even in the cases of apparent incidental similarity). The < symbol signifies that the word order of similarities also varies between texts, meaning that the actual degree of similarity is less than the number figure indicates. With that said, here are the charts for the empty tomb narratives followed by the parallels for Mark 16:9–20.

Based on these comparisons, one would have a stronger case for saying that Mark 16:1–8 was literarily dependent on the other Gospel parallels than one has for Mark 16:9–20. Indeed, most texts of Mark care closer to their parallel pericopes than Mark 16:9–20 is to its various parallels.8 Of course, not many scholars make such a case because of prevailing assumptions about Markan priority. Since a different set of assumptions prevails for Mark 16:9–20, scholars employ different arguments and make different claims.

Since the following parallel will come up later, I should also present the juxtaposition of Mark 16:12–13 with Luke 24:13–35. I noticed in my response to Peter Head (linked above) that I had, in fact, missed other similarities here, and so here I provide the texts in their entirety, again following the Nestle-Aland version.

Obviously, I have to stretch things to make the similarity scores higher. But with one text being almost eighteen times longer than the other, there is a greater chance of figuratively throwing a dart and hitting a similar word than I mentioned at first. Several words appear in completely different contexts with different functions (one word that could have been counted, μετά, was not included because the functions are so different because of their positions and the cases of their complements). As far as can be discerned, these look to be incidental similarities. Even the phrase “two of them” has “two” in different nominal case in each text. Are we really supposed to put so much weight on the partitive phrase that follows “two” as being a clear indication of connection between these texts? If one text had only referenced “two [disciples]” instead of “two of them,” would Kelhoffer then have rendered the links between these texts as less probable? As we will see from his own exercise, the answer to the first is clearly “yes” and the answer to the second is most likely “no.”

Convoluted Comparison

How, then, does Kelhoffer address these deficiencies of comparison? On the one hand, as we will see in more detailed analysis below, he must overstate the significance of the parallels that have already been identified. On the other hand, he must bring in other texts beyond those noted above.

The result is a patchwork of imitation imagined through a process so impractical, unintuitive, and convoluted that only a scholar could have conceived it.9

16:9: Two words + Mark 16:2 (three words) + two words + John 20:11–18 (three words) + Luke 8:2b (five words)

16:10: John 20:15–16 (one word) + Matt 28:7 (one word) + John 20:18/Matt 28:8–11/Luke 24:9 (one word) + Mark 3:14 (four words) + three words

16:11: Three words + Luke 24:23 (cf. 24:5/Acts 1:3; one word) + four words + Luke 24:11 (one word)

16:12: John 21:1 (three words) + Luke 24:13a (cf. 24:13–27; four words) + John 21:14 (one word) + Luke 24:13a, 28a (three words) + Luke 24:28–35 (three words)

16:13: Two words + John 20:18/Matt 28:8–11/Luke 24:9 (one word) + Luke 24:9 (two words) + two words + John 20 (esp. vv. 8, 25, 29–31; one word)

16:14: One word + Mark 14:17–18a (one word) + one word + Matt 28:16–17/Luke 24:9, 33/Acts 1:26/2:14 (two words); + John 21:14 (one word) + ten words + Mark 16:6 (one word) + John 20 (esp. vv. 8, 25, 29–31, two words)

16:15: Luke 24:46 (three words) + Matt 28:19a/Luke 24:47 (one word) + Mark 13:10/14:9/Matt 28:19a/Luke 24:47 (four words) + Matt 28:19a/Luke 24:47 (one word) + Mark 1:1/1:15/etc. (two words) + three words

16:16: John 3:18ab (two words) + two words + John 3:18ab (five words)

16:17: John 20:30–31/etc. (one word) + one word + John 14:12 (two words) + two words + Mark 9:38 (cf. 6:13, six words) + Acts 2:4/2:11 (three words)

16:18: Six words + Luke 10:19b/Mark 9:1 (two words) + two words + Mark 6:5, 13 (four words) + three words

16:19: John 20/Luke 24:34 (one word) + John 20:30 (two words)10 + John 20/Luke 24:34 (one word) + one word + Mark 1:14/14:28 (four words) + Luke 24:51/Acts 1:2/1:11/1:22 (four words) + one word + Mark 14:62/Acts 7:55–56 (five words)

16:20: Two words + Mark 6:12 (two words) + Luke 9:6 (one word) + John 20/Luke 24:34 (two words) + two words + Mark 2:2/8:32/etc. (two words) + four words + John 20:30–31 etc. (one word)

This convoluted scenario devised for explaining the supposed non-Markan composition of Mark 16:9–20 can perhaps be salvaged to some degree by one or two ways. One, we could identify analogies to show that, regardless of how implausible this appears on its face, this convoluted patchwork did actually happen. Two, more importantly for this specific case, we would need to assure the arguments made for the various links are so strong that an alternative conclusion is itself implausible. We will consider the second possibility below, but for now, let us turn to the question of analogies.

Analogies

Two possible analogies I can think of are composite quotations of Scripture, such as in the NT, and Gospel harmonies. The first is a problematic analogy, especially since those occur in cases where authors tend to draw attention to their quoting from another source, whereas here Kelhoffer claims, “On the contrary, the LE’s author did not want to advertise that he was borrowing extensively from other writings; rather, he wished to compose an addition to Mark that would be esteemed by others.”11 Those quotations, at least in the first one hundred years of Christian writings (I cannot say for sure after that), also are not as long or as complex as this one that was supposedly composed mostly (but not entirely) out of imitation.

The second possible analogy of harmonies is also problematic for two reasons. One, insofar as we have access to early Christian harmonies today, they appear to have operated by a mix of smoothing differences and drawing on parallel texts, rather than from such a wide array of texts (this is not counting Augustine’s more extensive and explanatory work that is clearly of a different character than the ending of Mark). That is, they did not compose such bodies of text by drawing from so many locations of texts, whether or not the text was pertinent to the specific pericope. And, of course, no one could reasonably mistake this text for a harmony in light of the fact that this supposedly latest ending of the Gospels was composed with access to all of the others and managed to be done without any attempt to more easily harmonize with one or more of them. In fact, as we can see from Eusebius (Gospel Problems and Solutions, “To Marinus” 1), the text raised other issues for harmonization.

Kelhoffer himself suggests two analogies of specific texts where “the literary procedure is similar.”12 These analogies are the Epistle to the Laodiceans and 5 Ezra. He even specifically says of the former that it “provides an analogy to the LE in that both the occasion for writing and the method of composition parallel those which have been argued in the case of the LE.”13 But I guess he must mean this in the broadest sense because the imitations of Paul in the pseudonymous Epistle to the Laodiceans are not drawn from so many locations in such varying sources in such a short space to account for one or two words here and two or three words there like we see proposed for this text. It is not a complete cut-and-paste job either, but much of the syntax is based primarily (though not exclusively) on one source. Note the following comparisons:

Of course, comparison is complicated at the minute level by the fact that the former letter is only extant in Latin, though there are Greek reconstructions, and the Latin is not always reflective of the Vulgate tradition.

On the other hand, 5 Ezra, a Christian addition to 4 Ezra that may have been composed in the late second or third centuries, draws from a number of OT texts and other sources (like 1 Baruch). But this is a mix of allusions, appropriations of language drawn from memory, and quoted material. While many connections can be made with various OT passages, it is absurd to suggest that 5 Ezra was composed by combing over dozens of mss to find a word or a phrase here and there to make the various connections that scholars have noted.

After all, what Kelhoffer proposes is a rather luxurious process, in addition to being convoluted. The supposed non-Markan author would need to have mss of all four Gospels at hand. He would need to go back and forth between them and not in sequential order, sometimes jumping over large amounts of content to find a word or a small selection of words here and there. He did this all without losing his place or creating a syntactically jumbled mess. At least, that is what one would have to suppose, unless there was a lengthy process of editing. And he did all of this to produce just over 160 words to end a Gospel in a way that is not especially robust or detailed, despite his apparently having so much time on his hands to pore over all these documents to painstakingly compose a text mostly out of small pieces of other texts.

In the end, it appears that someone besides Mark performed the equivalent of dumping five 1,000-piece puzzles into a pile and hastily assembling the mess into his own 1,000-piece puzzle, since he was apparently trying to do it quickly. That scenario may sound preposterous, and that is because it is, just like this theory of this coherent, albeit rushed, story being assembled in this fashion. Moreover, the supposed non-Markan author has managed to do this while having access to all of these endings of other Gospels (as well as, apparently, Acts). And yet he has not made an ending that is more like any of them than it currently is (no segment, much less the entire ending, has a verbal similarity of 50% or more with a parallel, nor are they even as close with parallels as Mark is with other Gospels in most of the segments in the empty tomb narrative). Nor has he made an ending that is more robust than any of the other Gospels, as Mark 16:9–20 is the shortest ending of the Gospels after the empty tomb narratives. Finally, one must wonder why a scribe with all of these endings at hand would not have written something more harmonized with the other Gospels than the text currently stands (especially in light of attempts to harmonize Gospel texts as early as the second century in which this text was supposedly composed).

Categories of Comparison

Thus, we must now turn to the actual details of the analysis to see if the arguments are so strong that this prima facie implausible scenario can be rendered plausible. This will not be quite a complete analysis of his arguments, as that could ultimately be even longer than his second chapter. Rather than go through the text in order and address the same categories in turn over and over, I have decided to divide his analysis by categories of comparison. There are plenty of terms he cannot source, and so he simply attributes them to the non-Markan author’s innovation. My comments on that category will be brief. Other features are said to Markan, but they are only imitations of Mark. Still other features are said to be almost Markan but diverge in ways that show they are not Markan. This third category is a subset of the first, but there are peculiar arguments here that need to be addressed. Furthermore, there are features Kelhoffer insists are drawn from resurrection narratives in other Gospels. And finally, there are some features that are said to be drawn from other parts of other Gospels and Acts. Again, some features straddle multiple categories, so one should not think of these as watertight.

Unsourced Terms

The larger category here consists of fifty-nine words scattered throughout the ending. This is another way of saying that Kelhoffer identifies parallels/sources14 for 106 out of 165 words. The rest fit in this category. Not much needs to be said here that will not be addressed below. But it is notable that, despite how detailed Kelhoffer’s analysis is, there are curious deficiencies in the attention to detail here. For example, in commenting on the reference to baptism in v. 16, he says, “From Mark one never learns that receiving baptism has salvific implications.”15

There is a larger discussion about the interpretation of this text that I am not going to wade into here. It is largely impertinent to Kelhoffer’s analysis anyway. The problem is that one could use the same kind of argument to dismiss Matthew as having written Matt 28:19. After all, one never learns from Matthew—once you dismiss Matt 28:19—that Jesus regarded baptism as important for anyone but himself. Indeed, none of the Gospels provide us with an explicit sense of how Jesus thought of baptism as something his followers should practice prior to the ends of their respective narratives.16 Even John 4 does not convey why, precisely, Jesus’s disciples were baptizing. But as with Matthew, would it not make sense for something about baptism to be said here in the commission to Jesus’s disciples? Of course, this is a regular oversight in Kelhoffer’s analysis: the lack of consideration for how the development of the narrative might contribute to the text.

Markan Features (But not Actually by Mark)

“Those Who Had Been with Him”

I noted in my first post how the participial phrase in τοῖς μετ’ αὐτοῦ γενομένοις v. 10 is often taken as non-Markan, since the precise phrase does not appear anywhere else in Mark. However, I also noted analogies of similar phrases elsewhere. Kelhoffer takes the minority approach on this issue and acknowledges that it is similar to Mark, but he still says,

The most analogous construction in Mark is the calling of the twelve in 3:14 … Someone wanting to remain consistent with Markan style could change the subjunctive ὦσιν (designating the purpose that they would “be” with Jesus) to the participle γενομένοις (indicating that they “had been” with him). Such perceptiveness to the subtleties of the style of 1:1—16:8 bespeaks an author who had read Mark very closely.17

This claim is ironic for how out of line it is with other claims of supposed non-Markan elements. Indeed, only twenty-nine of the 106 imitated words (and of the 165 total) are attributed to Markan imitation without admixture of other sources. How closely did this supposed non-Markan author read Mark if his imitation failed this many times? After all, he was trying to pass it off as Markan, right? How, then, could he have read Mark so closely and still been so inattentive to how supposedly non-Markan his text was?

This is also another case in which he assumes that the differentiation of this text from 3:14 is due to the author changing a subjunctive to a participle simply because of wanting to imitate Markan style without the context really playing a role in the analysis. As it is, the prepositional phrase had been used several times in Mark with reference to Jesus and his disciples (3:14; 4:36; 5:18, 37, 40; 14:33; cf. Luke 24:33), but the precise grammatical construction would not have occasion to be used in Mark prior to 14:50. This is when the disciples flee and thus their being “with him” would have a past-perfect tense, so to speak (as that is how we often translate it).

The Gospel

To the earlier point about just how Markan this text is supposed to be, his comments on the use of τὸ εὐαγγέλιον in v. 15 are worth noting. This term that appears here is also elsewhere in Mark’s Gospel twice as often as in the longer Matthew (1:1, 14–15; 8:35; 10:29; 13:10; 14:9). And its presence in the beginning and here signals its significance to narrative framing. Instead, Kelhoffer suggests that the use of the term here “could have originated with Mark or someone intending to ‘finish’ his work who had read the seven Markan uses, beginning with Mark 1:1. Its presence in 16:15 only supports that whoever wrote this passage succeeded in making it look more Markan than Matthean, Lukan of [sic.] Johannine.”18 By Kelhoffer’s own analysis, the author must have failed and not succeeded, for only a small percentage of the word count even looks Markan. Moreover, of the 106 total imitated words he claims one is from Matthew without admixture, thirty are from Luke-Acts without admixture, twenty-five are from John without admixture, eleven are from mixtures that include Mark, and ten are from mixtures that do not include Mark. By this account, I am not sure how a supposed non-Mark author was successful in making the text “look more Markan” in this analysis.

More Confused Reasoning

A term from v. 9 attributed to Markan imitation is πρωΐ. This timing word appears more often in Mark than any other NT text (1:35; 11:20; 13:35; 15:1; 16:2). In fact, if 16:9 is included, Mark accounts for half of the uses of the term in the NT. But instead of at least allowing the possibility that this is a sign of Markan writing, since he is already committed to this being a non-Markan text from the second century, Kelhoffer says, “A likely source for this word is the timing of Mark 16:2.”19

In his attempt to explain the use of one word in v. 14 (ἀνακειμένοις), he posits a connection to the scene of the Last Supper in Mark 14 (specifically vv. 17–18a): “Although the verbal similarity of these passages is not striking, their function and context suggest that there may be some connection…. When one adds these similarities to the fact that no other NT evangelist presents a post-resurrection scene with the disciples already reclining at table, it [sic.] plausible that Mark 14:18a may have had some influence on 16:14.”20 It is apparently far too simple to suppose that this is a word the author knew, and the occasion arose for using it. It must be intentional imitation of something.21

He even supposes the following process to explain exactly how four words of Mark 16:18 (ἐπὶ ἀρρώστους χεῖρας ἐπιθήσουσιν) were composed:

It may thus be inferred that the author of the LE went through the following steps in composing 16:18c. First, he consulted Mark 6:13 (πολλοὺς ἀρρώστους καὶ ἐθεράπευον) and then embellished this summary by substituting the verb ἐπιτίθημι and mentioning the laying on of hands in the slightly longer summary of Jesus’ own activity in Mark 6:5 (εἰ μὴ ὀλίγοις ἀρρώστοις ἐπιθεὶς τὰς χεῖρας ἐθεράπευσεν). Moreover, the LE’s author found it awkward to start a phrase with the ἀρρώστοις of 6:5 and added the preposition ἐπί to signal the beginning of a new thought to the reader. In changing the participle (ἐπιθείς, 6:5) to the main verb of the sentence, he had no need of the verb θεραπεύω used in both 6:5 and 6:13.22

If this is supposed to be how the text is explained, one wonders why this author saw no need for the verb that appears in both of these other texts, except that it is convenient for the source theory. After all, it could still be joined with the other verb via a conjunction. Or it could have been made an infinitive to convey the purpose for laying hands (a subjunctive, particularly with a conjunction, would also work for this purpose). Maybe it is actually not necessary to posit that certain elements of these texts were copied while arbitrarily dropping a key element. It is as probable, and less convoluted, that this came from Mark and he did not elaborate here to match his earlier text simply because he had no intention of doing so (since it is not as if he was looking directly at that text while writing this one).

Conversely, when it comes to the use of the conjunction ὅτι in this same verse, he can say more simply, “there is every reason to believe that Mark or, for that matter, most any other early Christian author could have written this word that was used frequently in this way in Koine and other dialects of Greek.”23 I do not disagree. But it is curious why this explanation does not arise more often, especially for rather common terms and phrases he will attribute to being from either Mark or other sources. In the former case, he takes ἐξελθόντες ἐκήρυξαν in v. 20 as being from Mark 6:12 because the same two words are used,24 but this is somehow not a signal of actual rather than seeming consistency with Mark.25 Similarly with the reference to “the word” as a shorthand for the message of the gospel, he finds this to be an imitation of Mark rather than something that could have been written by Mark or even something that did not need to have a particular source posited, since we find it at many points in the NT.26

Mark-like Elements with Apparent Divergence

Resurrection Terminology

This category is much more common in Kelhoffer’s analysis, as the elements point either to a non-Markan author who may or may not be failing to imitate Mark (if he is not simply innovating) or to elements adopted from other texts. This begins with the very first word of v. 9: ἀναστὰς. I have gone over the uses of the term ἀνίστημι for referencing resurrection in the NT here. Some of these cases are from Mark, but Kelhoffer insists that this text should be distinguished from those cases. Why? He explains:

A closer look at Markan style reveals the opposite, however: at six points the evangelist consistently employs the aorist active participle to denote the act of rising from a sitting to a standing position, and not the resurrection. [Mark 1:35; 2:14; 7:24; 10:1; 14:60; cf. Mark 14:57] Such a selective use of the participle is not particular to Mark, since Luke also reflects it in passages not parallel to Mark (Luke 1:39, 4:29, 4:38; Acts 5:17, 5:34, 9:18, 10:13, etc.). In fact, there is no participial use of ἀνίστημι in the NT Gospels or Acts which refers to the resurrection.27

He even says that this use is “not only non-Markan but atypical for the NT as a whole: any imitator could use the right vocabulary word, but only a more careful observer would also write a verbal form that Mark also used.”28 Based on Kelhoffer’s earlier characterization of this writer, I thought he was supposed to have been such a careful observer, since he was someone who “read Mark very closely.” Finally, he says, “In addition, while the NT usually speaks of Jesus having ‘been raised,’ Mark 16:9 uses the active participle of another verb. Thus, the word choice, verbal form and voice are distinctive.”29

There are a few problems with this analysis, apart from how much weight is given to a single word. First, Kelhoffer has made an error of fact, not only of interpretation. Acts 13:33 uses an aorist active participle of slightly different spelling derived from this same verb, as does Acts 17:31.30 This also shows how Luke sharing the same tendency as Mark is an inaccurate observation. It is an unusual construction in the Gospels and Acts (as well as the NT as a whole), but it is by no means “distinctive.”

Second, it is not as if the aorist active participle itself conveys the sense of resurrection or an alternative. This is not true of any tense or mood form of this word or any of the others used for resurrection. The sense is dependent on context. To focus on this particular verb, Mark uses it in reference to resurrection in Mark 5:42; 8:31; 9:9–10, 31; 10:34; 12:23, and 25 (setting 16:9 aside for now). The first case is the only one in the aorist indicative verb form, and it is notable for three reasons. One, it comes immediately after an imperative form of a different verb in the previous sentence (ἔγειρε in Mark 5:41), which illustrates how overlapping and interchangeable these terms are, meaning that focusing on terminological differences in this respect is not typically going to tell you anything about whether or not Mark could have written something. Two, it is the only other case of referring to the raising action in the past tense with this verb. Three, it is the main verb rather than being used in a context where it is conveying temporal setting or some other adverbial function, so it is not clear why it should have been a participle. Conversely, there is nothing inappropriate about its use in 16:9 for Mark, who, by Kelhoffer’s own references, is clearly capable of using this form.

The other uses are either aorist infinitives (8:31; 9:10), aorist subjunctives (9:9; 12:23, 25), or future tense forms (9:31; 10:34). The other aorist forms would not convey absolute time for past reference, of course. They would also not be as useful for a clause in which the action of resurrection is fronted while also being rendered subordinate to a main verb (that of “appearing” in 16:9) and conveying that it happened prior to the main verb. It is also differentiated from the other uses in that most, if not all, of the ones Kelhoffer notes function as attendant circumstances. This function does not itself differentiate resurrection from non-resurrection uses. The differentiation depends on context.

Third, as I noted before, Mark is not averse to using both verbs (as well as ζάω, which appears in 5:23 and 16:11) in a short space to refer to resurrection. It is a larger gap here than in ch. 5 (or in ch. 12 for that matter with 12:25 and 26). Nor is there some great significance in using the active participle as opposed to the middle-passive form of the other. The latter is often intransitive rather than a true passive, including in the participial form (Matt 9:25; 12:42; 14:2; 16:21; 17:23; 20:19; 26:32; 27:52, 63–64; 28:6–7; Mark 6:14, 16; 14:28; 16:6, 14 [participle]; Luke 9:7, 22; 11:31; 24:6, 34; John 2:22; 21:14 [participle]; Rom 6:4, 9 [participle]; 7:4 [participle]; 8:34 [participle]; 2 Cor 5:15 [participle]; 2 Tim 2:8 [participle]).

We will have occasion to comment on another resurrection verb later, but for this category we can focus on the comments made about a certain construction involving the use of ἐγείρω. In commenting on two constructions of ἀνακειμένοις αὐτοῖς and αὐτὸν ἐγηγερμένον, he says, “Of the 750 Markan uses of αὐτός, there are only nine occurrences with a participle. By contrast, in the LE a participle is used with this pronoun in two of nine instances. The relative percentages of 1.2% (Mark) and 22.2% (LE) suggest that an author not seeking to imitate Markan style penned ἀνακειμένοις αὐτοῖς and αὐτὸν ἐγηγερμένον in Mark 16:14.”31 Later, he writes specifically of the form of ἐγείρω that it “appears elsewhere in the NT only in 2 Tim 2:8. Five Markan uses of ἐγείρω could point to an imitation of Markan style in 16:14, but the evangelist never uses a participial form of this verb. It is possible that the LE’s author chose this participle to complement Mark 16:6.”32

In response to the latter claim, the simpler solution is once again not allowed that this is simply consistent with Mark’s use of the common resurrection verb in Mark 5:41; 6:14, 16; 12:26; and 14:28 (as well as 16:6). The participial use is once again appropriate to convey a temporal sense (cf. John 21:14; Rom 6:9; 8:34; Eph 1:20). In 16:14, the participle is referring to what had happened so that others could see him, and so that he could appear in the present time. The other use in 2 Tim 2:8 appears to be an anarthrous adjectival participle serving as a description of Jesus Christ who has been raised from the dead. Here, as in the indicative, the perfect conveys a notion of a completed action that establishes a state producing continuing results. Such an idea is reflected in Mark 6:14, where Herod’s supposition that John the Baptist has been raised from the dead has the continuing results of explaining why Jesus is able to do what he does. The other uses of the perfect appear in 1 Cor 15. The first appearance in v. 4 marks the event of resurrection out from the preceding and succeeding series of aorist verbs that refer to past events (namely, that he “died,” “was buried,” and “appeared”). The results of this past action still resonate for the audience, and it is this action that brings forward the results of the previous actions, for it was the dead and buried Jesus who has been raised. In vv. 4 and 20 Jesus’s resurrection serves as the foundational condition for the rest of the gospel proclamation and Paul’s eschatological teaching; while the emphasis of the verbs may be on the completed action, the resulting state is also in view (particularly in v. 20). In vv. 12–14 and 16–17 Paul engages the hypothetical situation of if Christ had not been raised and the results extending from the non-occurrence of this foundational event.

One wonders where else Mark was supposed to have used the participial form, much less the perfect participial form. The first use in Mark is an imperative. The second use, as noted above, is a perfect indicative. The third is an aorist indicative. The fourth is a present indicative that has a futuristic function in this context. The fifth is an aorist infinitive in a temporal clause referring to an event still to come. And 16:6 is also an aorist indicative. Given the variety of uses, including of the perfect tense, are we supposed to think Mark was incapable of writing in this form? Other than a larger presumption about who wrote this text, why could Mark himself not have written consistently with 16:6?

In response to the former claim, I must admit I was boggled by how absurd this logic is. Mark obviously uses this construction elsewhere, but what is supposed to render it as non-Markan is proportion. And this is for something that is not even that peculiar a construction. If we were to compare like-for-like with a text of similar proportion from Mark, we could look to Mark 14:32–42 (181 words).33 There, we would find the third-person pronoun being used with a participle two out of ten times (specifically in vv. 37, 40). Two other cases from the same text could be added in that they are part of larger participial clauses.34 That is either two or four out of ten, which hardly seems inconsistent with two out of nine in a text of similar size. Clearly, such constructions are not evenly distributed throughout Mark. Its presence does not work as a signal of non-Markan authorship.35

First Things

To move on from resurrection terminology, another text that he says diverges from what Mark would surely write is the phrase πρώτῃσαββάτου. Supposedly, “The LE’s formulation, then, is best understood as a deliberate attempt to achieve agreement with Mark’s timing while improving his wording [from 16:2].”36 It is difficult to know in what sense this is supposedly “improving” the wording, since Justin Martyr saw these expressions as equivalent (Dial. 41.4).37 And if that was its function, one would think there would be more evidence of an alteration of the term in 16:2 to fit with that in 16:9, but I have looked in vain for manuscript evidence of such a sensibility among early (or even medieval) Christian scribes. In fact, the phrasing is used not only by Mark and the other Gospel authors at this same point in the story, but it also appears in LXX Ps 23:1; John 20:19; Acts 20:7; and 1 Cor 16:2. We also see similar phrasing in Justin, Dial. 27.5. Rather, this simply seems to be a way of reiterating what Mark has already said with different terminology (not “improved” wording) to establish that this event happened on the same day, that Jesus had arisen early on that same day, and now the focus is on Jesus’s action in appearing to Mary Magdalene rather than on the action of the women like it was earlier.

Another argument of “unusual, therefore un-Markan” concerns the use of πρῶτον in this same verse. He says, “In 32 of 34 occurrences in the NT Gospels, this adverb describes the prior of two items as opposed to the first in a series of distinct events” and that the use of the adverb here “probably comes from the hand of the LE’s author, who offers verses 9–10 as the first of Jesus’ three appearances.”38 The exceptions he allows are Matt 17:27 and Mark 4:28. Of course, that in itself undermines the force of his argument. If a text he takes to be Markan uses it this way, why can another not do so and still be Markan, unless one simply begs the question?

The restriction of scope to the NT Gospels is arbitrary, of course, since it is not as if this body of texts defines how such a common adverb can be used. I am also not sure how he arrived at this count, since I found a number of examples from the Gospels that I would not grant follow his stated pattern.39 One example he gives of the pattern is Mark 13:10,40 but it is far from clear how this is so precisely because so many other events follow thereafter. The same could be said for Luke 21:9. Nor is it clear how the “first” in John 1:41 is only a first of two things when it is applied to Andrew finding Simon and then saying something to him and then bringing him to Jesus (in v. 42). Likewise, I wonder how the “first” in John 18:13 when Jesus is “first” brought to Annas is only the first of two things. Beyond the Gospels, one can see other uses of this adverb in Acts 3:26; 7:12; 15:14; 26:20; Rom 1:8; 15:24; 1 Cor 11:18; 12:28; 1 Tim 2:1; 5:4; 2 Tim 1:5; 2:6; Jas 3:17; 2 Pet 1:20; and 3:3. Nor can Kelhoffer logically exclude consideration of these other texts without begging the question for his claim of why the text uses this term.41 These examples show there is, in fact, nothing unusual about this use.

Exorcism

One more example from v. 9 will also need to be addressed later in relation to Luke 8:2, but we can for now address his arguments about it being Mark-like with divergence here. First, he says that the “change in the LE from the preposition ἀπό to παρά is perhaps neither more nor less Markan.”42 And yet he follows that up in a footnote later saying, “Conversely, Gerhard Hartmann calls attention to the Lukan preference for ἀφό as opposed to the typical Markan usage of παρά … Viewed in this light, the adaptation of Luke 8:2b could be understood [sic.] an attempt to make Mark 16:9 appear more Markan.”43 Aside from the contrast with what he said in the main text (and the author apparently thinking one synonymous preposition was going to help shore up his apparent failures elsewhere), I genuinely do not know what he is talking about here. The precise number of uses for prepositions will depend on the critical text you use (as this is not an uncommon area of variation, particularly as synonymous expressions might be used), but on any count, Luke uses both prepositions significantly more often than Mark and Mark uses the former more often than the latter. Moreover, most texts of Mark 16:9 do actually have the former preposition rather than the latter.

He also makes this confusing claim to discredit the use of exorcism terminology:

Above it was noted that Mark infrequently uses ἐκβάλλω for specific exorcisms but reserves this word for describing exorcisms in general. Ironically, however, it would follow that the form of Luke 8:2b (ἐξεληλύθει) could be considered more “Markan” than the LE’s ἐκβεβλήκει. A change by the LE’s author probably stems from the desire to be consistent with the verb used also in Mark 16:17c (δαιμόνια ἐκβαλοῦσιν; cf. Mark 9:38) and to emphasize the role Jesus had played in casting out the seven demons.44

As he shows in his own analysis, Mark 7:26 is a reference to a specific exorcism, and 9:18 and 28 refer to others attempting exorcism in a specific case. Thus, it is hardly a “reserved” term for general reference. The term is in question is, of course, not “more Markan” (particularly since the other Synoptics use it more often), but the use of one term as opposed to another is driven by whether the focus is on the action of the exorcist (as here) or the action of the demon(s) (as in Mark 1:26; 5:13; 7:29–30; 9:26). There is no need for this to have been a “change” of a text.

Pronouns

With v. 11, the subject of the use of pronouns in this text is broached. This is something that often comes up with arguments against the authenticity of Mark 16:9–20. In the case of both kinds (κἀκεῖνος and ἐκεῖνος), we see more “unusual, therefore un-Markan” reasoning.45 The first kind of pronoun, being merged with a conjunction, is obviously more unusual. While Mark uses it, Kelhoffer tries to differentiate the use in v. 11 from Mark 12:4–5 by saying, “In the Parable of the Tenants the word denotes those in a succession subsequent to an initial example, but in 16:11 those who disbelieve are the initial example.”46 This gives the impression that the pronoun could have only been used in the one way by Mark if Mark had written it. Maybe the pronoun is flexible and can have different functions in different contexts.

The second is even more frequently noted, despite how common the pronoun is, because of its absolute/substantive use. There is certainly an atypical density of this usage here (16:10, 13, 20), which I have explained as being indicative of the summary nature of this text. He himself must admit that the pronoun is used in the absolute/substantive fashion in 4:11, 20; and 7:20 (besides the use of the compound in 12:4–5), but he still tries to split hairs here by saying (while still admitting 7:20 as an exception) that these are part of Jesus’s teaching rather than the narrator’s use.47 Again, once you have admitted that Mark used it once in a certain way, there is no reason to think he is restricted from doing so again.48

In an attempt to extend this point, he says the following:

By contrast, when Mark employs a demonstrative pronoun absolutely, it is much more common for him to use οὗτος rather than ἐκεῖνος or κἀκεῖνος. In seventeen Markan occurrences of οὗτος, twelve are absolute [2:7; 3:35; 4:4; 6:3, 16; 9:7; 12:7, 10, 40; 13:13; 14:60, 69] and five are attributive [4:15–16, 18; 7:6; 15:39]…. Therefore, if Mark is to use a demonstrative pronoun as a substantive, he is much more likely to use οὗτος (twelve times) than ἐκεῖνος (three times) or κἀκεῖνος (two times). The LE, by contrast, never uses οὗτος, but instead employs κἀκεῖνος (twice) and ἐκεῖνος (three times) absolutely.49

Imagine, if you will, making an argument based on the fact that one demonstrative pronoun, which is more common in all the Gospels and Acts than the other demonstrative pronoun, appears more often than the other. In fact, there is not one book in the NT that features the far demonstrative pronoun more often than the near demonstrative pronoun (and I am guessing, though I have not done the study myself, that it is thus also more common for every author to use it as a substantive more often than the other). But this is where we are.

His argument is also confusing because at times he simply refers to the “absolute” use, but his footnote points specifically to examples of a personal substantive. And then in the main text again he says that this ending never uses the near demonstrative pronoun, when it actually does (16:12, 17), the latter instance of which is an attributive. But the argument can only be applied (partially) if one assumes again that he is writing specifically of the personal substantive use.

Even by these implied restrictions, Kelhoffer has for a curious reason excluded many forms of the near demonstrative pronoun from his analysis. Otherwise, he would have identified far more attributive uses than the five he mentions (4:13; 7:23; 8:12 [2x], 38; 9:29; 10:5, 30; 11:23, 28; 12:10, 43; 13:30; 14:4–5, 30, 36, 58, 71). He also missed that Mark 4:4 is not an example of this demonstrative pronoun (or its use) while 14:9 is (though it is a feminine form).

This curious treatment extends to “The contrast with the fourteen Markan uses of ταῦτα is illuminating: the evangelist always uses ταῦτα absolutely or with πάντα. As a result, both the use of ταῦτα in Mark and the more complicated syntax of 16:17a point to distinctiveness of σημεῖα … ταῦτα.”50 Again, this whole point appears to be based strictly on this form and not on the use of the near demonstrative pronoun in its various forms more generally, as we have seen other uses of the pronoun attributively and absolutely/substantively. Of course, the fact that the term is used in line with his observations in v. 12 is not even potentially to the ending’s credit because another point is being promoted here.

Of course, the whole approach here is flawed. The use or non-use of terms depends on context. But this stylistic analysis treats it as a matter of probabilities (and presumably evenly distributed probabilities at that). I am curious about what human actually writes with such robotic repetition and precision.51

Other Common Terms

At another point, he moves from “unusual, therefore un-Markan” to positive declarations of what Mark could have written. In referring to a phrase in v. 12 (δυσὶνἐξαὐτῶνπεριπατοῦσιν ... πορευομένοιςεἰςἀγρόν), he declares, “While the evangelist could have written (only) the first participle (περιπατοῦσιν) there is no precedent with either word for such a complex syntax as dominates the whole of 16:12. The rather sophisticated syntax at this point in the LE also points to a different author.”52 We have gone beyond comparison with what Mark did write to statements of capability about what he even could write all on questionable bases. Apparently, Mark’s writing shows him incapable of using common Greek words, as the Gospel is now a compendium of his entire vocabulary. Moreover, his declaration that Mark could not have composed the complex syntax of v. 12 is based on comparison only with other uses of the participial form he identifies.53 Seemingly, once Mark used this participle, his ability to form complex syntax becomes limited until he begins another sentence. Of course, even restricting our analysis of Mark’s syntactical constructions to the other uses of this participle, we can see that his analysis is not accurate for 11:27–28. Nor is it true of 8:24, where he has missed another participle being present before this one. And it is especially not true of 6:48–49. Both verses are part of sentences with multiple participles. 6:48 has two participles before this other participle, as well as four prepositional phrases, two indicative verbs, and two infinitive verbs. 6:49 is less complicated with one additional participle, one prepositional phrase, and three indicative verbs. And this is without broadening our scope of syntactic analysis to the rest of Mark.

Even common expressions (whether in Greek in general or among Christians) must be due to something other than simple Markan writing. For example, the use of the emphatic negative οὐ μή, incredibly common though it is, must be attributable to a particular source, such as a mix of Mark 9:1 and Luke 10:17–19.54 And it is only these two words that are so attributable, at least according to Kelhoffer. For another example, you would think the reference to Jesus sitting at God’s right hand in 16:19 is such a common element of the NT and Christian tradition that there is no reason to posit a particular textual source. Though it is a common element, it is subject to some variation in phrasing across texts. Even this is thought to be subject to borrowing, specifically of a mix of Mark 14:62 and Acts 7:55–56.55 There is no way the author could have simply considered this variation of the phrasing appropriate to write. It must have come from some other text(s) the author had at hand.

Cited from Other Resurrection Stories

In this other category, we see an interesting switch. While Kelhoffer would disqualify a feature from being Markan because the precise form and sometimes the precise function did not appear elsewhere in Mark, when it comes to connecting a feature to the other Gospels, it only needs to be determined as close enough. This is not the only problem with this category, but we will see examples of this and other points as we go.

Resurrection Terminology

To begin the same way we began the last section, we must consider the other resurrection verb used here: ζάω (v. 11). This is a feature not only consistent with Mark’s use of the verb to refer to Jairus’s hope for Jesus raising his daughter (Mark 5:23), but it fits with many other uses of the term for resurrection elsewhere in the NT (besides the parallel in Matt 9:18, see Luke 15:32; 24:5, 23; John 5:25; 6:51, 57–58; 11:25–26; 14:19 [2x]; Acts 1:3; 9:41; 20:12; 25:19; Rom 6:10–11, 13; 8:13; 14:9; 2 Cor 13:4 [2x]; Gal 2:19, 20 [4x]; 1 Thess 5:10; Heb 7:25; 10:20; 1 Pet 2:4; 4:6; Rev 1:18; 2:8; 13:14; 20:4–5).56 Such a common feature as this isolated term might suggest that it is not something so peculiar as to need another textual source.

But Kelhoffer attributes the use of this one word to a particular author other than Mark. In an excursus before his point-by-point analysis, he says, “Moreover, the most analogous uses of the verb ζάω appear in Luke-Acts (Luke 24:5, 24:23, Acts 1:3, 2:8, 25:19) and Revelation (Rev 2:8; cf. 13:14, 20:4—5) rather than in extracanonical writings…. As a result, the only plausible source for ζῇ is Luke-Acts and possibly Revelation.”57 Later, he says that the uses in Mark 5:23 and 12:27 (which is not a direct reference to resurrection, literal or metaphorical), “do not indicate much regarding style or use of traditions. The occurrence in Mark 16:11 may reflect some knowledge of Lukan traditions which refer to Jesus as ‘living’ after the crucifixion.”58 That is all he has to say on the subject as far as argumentation goes.

Only in the broad sense is he correct that Luke represents the most analogous use in that Mark 16 and Luke 24 specifically apply it to Jesus in the context of their resurrection narratives. But with that being the case, it is not as if only one author could have had the idea of using this verb sometimes used for resurrection in application to the resurrected Jesus. And the other uses in Acts and Revelation would not need to be referenced at all if this is supposed to be the most analogous use. I do not know why he references them anyway when there are other cases.59 John 14:19 applies it in an anticipatory sense to Jesus’s resurrection. Acts 1:3 reflects a summary of Luke 24, but the vocabulary is also consonant with 9:41, where it refers to Peter presenting Tabitha alive after raising her from the dead (cf. 20:12), which further demonstrates how it fits as a description for both temporary resurrections and the eschatological resurrection. Acts 25:19 is a summary of Paul’s proclamation about Jesus being alive. Romans 6:10 refers to Jesus’s resurrected life using the same form as Mark 16:11 (which none of the Lukan texts do; cf. 2 Cor 13:4), and 14:9 similarly refers to his resurrection in terms of his being alive again after his death. Peter refers to him being a “living” stone in juxtaposition to his being rejected (1 Pet 2:4). For whatever reason, Rev 1:18 was missed, but the other uses he mentions besides 2:8 do not apply to Jesus anyway.

Mary Again

When Kelhoffer feels the need to explain the reference to Mary Magdalene in 16:9 after the references in 15:47 and 16:1 (as well as 15:40), his explanation is, “A likely reason for this clarification is that the LE’s author knew of an appearance to this Mary in John 20:11—18.”60 Once again, this assumes that the writer could have only known this story not only because he knows the text of John, but also because he had the text of John before him. A simpler explanation is that Mark knew the story and reintroduces her here is that, for the first time, the narrative focuses on Mary and not the other women, and so Mark gives more information about her (which also anticipates a prophecy of Jesus in 16:17). Kelhoffer is not far off from this, except that he feels the need to posit another text as exerting influence here.

He also comments on the Greek form of “Mary Magdalene,” since the reference to her here differs from Luke 8:2, which he otherwise connects with her description. Yet again, he posits,

A likely explanation stems from Jesus’ appearance to Mary in John 20. The wording … is consistent in Mark, Matthew and John, but not in Luke. The likely significance of John 20 to the LE’s author is the fact that this passage reports Jesus’ appearance to Mary Magdalene and nobody else. The consistent wording of Mark 16:1 (perhaps also Matt 28:1) and John 20 was probably a sufficient impetus to motivate the LE’s author to deviate slightly from Luke 8:2b at this point.61

It is not enough to observe that this is the consistent way Mark refers to Mary in 15:40, 47; and 16:1 (cf. Matt 27:56, 61; 28:1; John 19:25; 20:1). Another text altogether needs to be posited as exerting influence. Furthermore, in the key story, one will notice above that Mary is not referenced in this full way. And even when the full reference is given in 20:18, the name is spelled differently in the critical text (though the majority of mss favor the typical spelling). But again, it is deemed close enough.

As Kelhoffer makes the common points about the demonstrative pronouns, he also claims the use of ἐκείνη in v. 10, in particular, “probably reflects some knowledge of Jesus’ appearance to Mary in John 20:15—16.”62 The simpler explanation is once again that this is a contextually appropriate usage of a common demonstrative pronoun. But in Kelhoffer’s view, it is preferable to posit an entirely different text as the source for this one word before citing an entirely different source for the use of the next word and then citing yet more texts for the word after that (see outline above).

Πορεύομαι

To that point, Kelhoffer makes the common argument about the use of πορεύομαι, although he adds the suggestion that it is connected with Matt 28:7–8.63 He further suggest that this is not coincidental because the next verb used after the participial form in 16:10 “also corresponds to the response in Matt 28:8 of the women.”64 For another participial use of πορεύομαι in v. 15 (it is only used as a participle in these sentences), where it is combined with κηρύξατε, he says, “Although the amount of verbal correspondence is not high, it is plausible that the LE’s author changed Matthew’s μαθητεύσατε [in 28:19] to κηρύξατε in light of Mark [1:14; 13:10; 14:9], Luke [24:47] or both writings.”65 He even calls this last example “The most striking case for literary dependence” of the Markan ending on Matthew.66

On the first point, it has often been observed that throughout the Gospel Mark uses the compounded verb of this verb as opposed to the simple verb, which appears in three participles here. As I have noted before, no other Gospel, or even Acts, uses only the simple or compounded form of the verb. Previously, I have cited the figure from Nicholas Lunn as 29:7 for Matthew, 3:16 for Mark, 51:16 for Luke, 16:2 for John, and 37:9 for Acts.67 But I am not sure how he got this figure after reexamining his work and the terms in the NT. By my own count (including instances of the simple verb, as well as διαπορεύομαι, εἰσπορεύομαι, ἐκπορεύομαι, ἐπιπορεύομαι, παραπορεύομια, προπορεύομαι, προσπορεύομαι, and συμπορευομαι), I have verified the counts for all the other Gospels and Acts, but I found that the proportion for Mark is 3:25 (I can only guess that a couple prepositions were missed in his count). The proportion is close to that of John, albeit reversed. In any case, it is not as if the simple form is inappropriate in any of the instances in this context (cf. Matt 28:11, 16, 19; Luke 24:13, 28; John 20:17).68 Unless we are to posit that Mark had some kind of revulsion to this common verb, there is no solid basis for claiming Mark would not have used this verb.

On the second point, I would think the better parallel for that verb would be later in the story. After all, as we see in my charts above, the verb appears in the context of Jesus appearing to others (Matt 28:10; Mark 16:13; cf. John 20:18 [particularly in the majority of mss, where the participle actually matches the verb used in Mark]). My guess as to why one part of Matthew is used for reference and not the other is due to the (false) impression of some density of connections that has been significantly overblown (again, see my charts above). Furthermore, there is no reason to disconnect it from Mark (5:14, 19; 6:30).

The last point is oddly incoherent. By his own admission, the amount of verbal correspondence between the texts is not high, yet he still calls it the most striking case for linking the two in a relationship of literary dependence. But this most striking case is one word in combination with a word that is supposed to come from an entirely different source. The “striking” dependence is merely the use of the participial form of πορεύομαι. It is also confusing as to why Luke 24:47 needs to be posited as the source of κηρύσσω. The form does not match what we see in Luke, but yet again, once we are talking about another Gospel, it is close enough. This is especially odd to propose when we note that κηρύσσω is Mark’s preferred term for proclaiming a message (outside of 16:15, 20, see 1:4, 7, 14, 38–39, 45; 3:14; 5:20; 6:12; 7:36; 13:10; 14:9).

Faith

Another supposed sign of Mark’s dependence on other Gospels is more thematic in the focus here on belief/faith and the lack thereof. Kelhoffer notes, “Unlike Mark 16:9—20, the Gospel of Mark does not offer an explicit definition for the content of this faith. Four other passages in Mark mentioning faith correspond to the above in that they also do not inform the reader’s understanding of the content of faith.”69 He will even go so far as to say later, “the different meanings Mark and the LE’s author typically associate with πιστεύω exclude the possibility of Markan authorship.”70

Of course, readers should be aware that faith, and especially the lack thereof, is an important theme in Mark, including for how it marks the disciples, whether in terms of not having faith (4:40) or of being hardhearted (6:52; 8:17). Kelhoffer somehow counts fifteen instances in Mark 1:1–16:8 that he describes as “Some belief not specifically with reference to Jesus.”71 How he gets to this conclusion, though, is obscure, since I do not see how the faith people have that Jesus will heal can be defined as not being “with reference to Jesus” (2:5; 5:34, 36; 9:23–24; 10:52). Nor is 4:40 marking something other than deficiency of faith with respect/reference to Jesus.

Apparently, since this text was written for Christians, that is not sufficient reason for the text to be implicit much of the time unless the author perceives some need for being explicit (even in John, where faith terminology is at its most prominent, the object of faith is not always explicit in the way that Kelhoffer looks for here). Mark 1:15 is a case that is especially anticipatory of the ending with the call to believe the gospel, though the story will give greater definition to that gospel (1:1). Strangely, Kelhoffer says of this text in particular, “Although τὸ εὐαγγέλιον is clearly an important concept for the life of the believer and mission of the community, these passages of the Second Gospel do not offer a clear picture of what is to be believed in Mark 1:15.”72 That is what the rest of the story is for, no? 8:35 and 10:29 also show how allegiance to the gospel is allegiance to Jesus, showing once again that faith in the gospel is definitely “with reference to Jesus.” Nor is any account given of why this is not appropriate narrative development: now that the content of the gospel has been more fully given with the happening of the major gospel events (with one more still to come in v. 19), this is a fitting place to be direct about the object of faith. Of course, in many cases the object was clear enough from the context that no explication was required (2:5; 5:34, 36; 9:23–24; 10:52; cf. 11:20, 23–24, 31; 13:21).

Yet another strange turn in this argument is his claim that “Ironically, the only verse in the Second Gospel that refers to belief in Jesus is one of mocking … (15:32). Such a difference between Mark’s subtlety in expressing the content of belief and the explicit, repetitive emphasis of the LE points to a difference in approach between the two authors.”73 On the latter point, I have noted that this is appropriate for the conclusion of the Gospel in light of the narrative development rather than being a pointer to a different author On the former point, this is manifestly not true. Several other times throughout Mark, Kelhoffer has insisted that Mark is not explicit or specific about whether the belief is “in Jesus” because it is not syntactically direct. But it is also not syntactically direct here. It is the same as the references to faith in the context of healing in that the object is not necessarily made explicit, but the context shows that it is clearly “with reference to Jesus” (see also 6:6; 9:19). It is true that the majority of mss have an object here (although this is a reading he does not cite in his actual quote of the Greek text), but if that is a point one wants to make in his favor, one must also accept the even stronger testimony in favor of an object of those who have faith “in me” in Mark 9:42.

There is also another example here of the absurd lengths to which Kelhoffer may go to make arguments based on terminology. He says in a footnote:

Mark’s choice of terms does not line up with those of the LE. The evangelist uses the substantive ἀπιστία (6:6; 9:24) twice and the adjective ἄπιστος once (9:19), while in the LE the verb occurs twice (vv. 11, 16b …) and the noun once (v. 14). Even though these terms in the LE could be an extension of Markan style, the depictions of disbelief in Luke 24:11 … and John 20 offer more plausible sources for this term.74

Yes, that is a basis for saying Mark 16:9–20 is inconsistent with Mark 16:1–8. This is not the first nor the last time such arguments will be made, but this is perhaps the supreme example of how so much is made out of such natural variation.

Verses 12–13

I have put this under one heading because there is much to unpack here. The first three words of v. 12 are attributed to another source—more specifically, John 21:1—because the precise construction does not appear anywhere else in Mark. But it is not as if Mark does not use the μετά + accusative construction elsewhere to convey temporal reference (1:14; 8:31; 9:2, 31; 10:34; 13:24; 14:28, 70). Yet this transition plus another one used in v. 19 (μὲνοὖν) is thought to suggest “that the LE’s author sought to imitate even the most minute details of John’s narrative.”75 One wonders, then, why the supposed non-Markan author produced the shortest ending of the four Gospels if he had all of them to work with. One also wonders why one who was paying this minute attention to John did not actually imitate more substantial details of John as opposed to miniscule particles. He also notes that the same form of the verb appears in Mark 16:12, 14; and John 21:14, even though the contexts are otherwise completely different.76

One might think that Kelhoffer makes these points to set up a connection between this story and John 21, but that is clearly not going to work in any sort of detail. Instead, he argues that the text is dependent on Luke 24:13 and following.77 We have already seen there is not a lot of shared language (even incidentally) between them, but Kelhoffer insists, “On the contrary, any author having only 11 words with which to capture the essence of Luke 24:13—27 would be hard pressed to offer a more comprehensive epitome than the LE’s author did.”78 Of course, this once again raises the question of why the author would have only devoted eleven words to supposedly telling the same story for which he was reliant on Luke 24 for or why we should think this story (if it is the same one) could only be known to the supposed non-Markan author by means of text. Again, why would an author who had all the other endings at hand, as well as the luxury of time to sort through all the documents to find the right word here and phrase there for his text, write something shorter than all of them? But this scenario requires positing someone with the luxury of time who is also pressed for time.

Also, to answer the implicit challenge, I offer the following two possibilities of eleven-word summaries that only use terms from the relevant portion of Luke 24, albeit with proper grammatical modifications.

Καὶ Ἰησοῦς συνεπορέυτο δυσὶν ἐξ αὐτῶν καὶ διερμήνευσεν αὐτοῖς τάς γραφάς.

Πορευόμενοι δὲ δύο ἐξ αὐτῶν εἰς Ἐμμαοῦς συμπορευθεὶς Ἰησοῦς εἰπεν αὐτοῖς.

The possibilities could be expanded further with not using the prepositional phrase, with further grammatical modification, or with expanding the scope to v. 35.79 And though he says it is a “comprehensive epitome,” the only details he can claim to be epitomized by Mark 16:12 end with Luke 24:17, while my summaries make clearer that the same story is being referenced and involve a larger scope of detail. The three-word phrase for “in another/a different form” is presumed to be correlated with v. 16, but this is not clearly so, since Luke has it that their eyes were kept from recognizing him more than that it was due to a difference in form. That is not to say these are not two ways of referring to the same characteristic of the same event, but it is not so obvious as Kelhoffer makes it seem.

In the above examples, I have relied on using the prepositional phrase ἐξ αὐτῶν because of how much significance Kelhoffer assigns to it:

Of the 39 NT occurrences of the partitive genitive expressed by ἐξ αὐτῶν, only two occur in Mark (14:69—70). The majority stem from the other Gospel writers, especially Luke. If one had to guess whether Mark or Luke was more likely to have written δυσὶν ἐξ αὐτῶν the far more likely choice would be Luke. The evidence thus suggests that, when the author of the LE wrote δυσὶν ἐξ αὐτῶν, he probably borrowed from a passage like, if not the same as, Luke 24:13.80

Once again, Kelhoffer focuses on only this specific form as being somehow especially significant for determining authorship/style/source. And yet again, we must note that if Mark used even once before, nothing precludes him from using it again, as Kelhoffer notes two examples here. Of course, if one broadens the consideration to other partitive uses of the preposition, one could also include 9:17; 14:18, and 20.

It is unsurprising if Luke uses any feature more often than the other Gospel writers simply because he wrote more text than any of them, especially when we include Acts. As a matter of fact, Matthew and Luke use the partitive expression with this specific form the same number of times in their respective Gospels (nine), but Luke also uses it seven more times in Acts. But that is a less significant problem with this argument.

A more significant problem, and a familiar one with Kelhoffer’s analysis, is how detached from reality such expectations of the use of language are. By this same logic, one could say “If one had to guess whether Matthew, Mark, or Luke was more likely to have written τότε, the far more likely choice would be Matthew. The evidence thus suggests that, when the other authors used the term, they probably borrowed from Matthew.” This is a term Matthew uses far more often than Mark, Luke, or both of them combined. And yet, one would not be justified at all in making this claim. Otherwise, we would not only need to assign all parallel uses of the term to borrowing from Matthew; we would also need to assign unparalleled uses of the same to this cause (Mark 13:27; Luke 13:26; 14:9–10, 21; 16:16; 21:10, 20; 23:30; 24:45).

Another reason Kelhoffer suggests these verses consist of borrowed elements from other texts is the presence of apparent seams in the narrative. Presumably, such seams as he supposes are due to the author searching the texts only for scattered words to use rather than paying attention to the details he used or did not use. The author was apparently in a luxurious situation with plenty of time to go through the texts looking for scattered individual words and phrases to use, but he was also in a hurry.

The first of these seams is the reference to Jesus appearing “in another form.” He observes that the first two appearances in vv. 9–13 “are quite parallel in form and content, adhering to the pattern of an appearance of Jesus, the obedient reaction of messenger(s) and a response of disbelief by others. Together they form a prelude for the climactic final appearance of Jesus in 16:14. There is thus no reason why the author of the LE would have sought to emphasize such a distinction between the two appearances.”81 He calls this an “internal inconsistency” that is “best explained in terms of the way in which this author made use of various traditional materials. Luke developed the motif of Jesus’ secret identity in the Emmaus story (Luke 24:13—27) over the course of this extended narrative. By contrast, the LE’s author never states explicitly that the identity of Jesus was hidden from the two disciples. He thus seems to have composed this verse for an audience who was familiar with some form of Luke 24.”82

What he is highlighting is a difference, not a clear case of internal inconsistency. It is not inconsistent for there to be a variation in structure. Nor is it inconsistent for a detail that to be introduced into a narrative without further explanation, though it may be unsatisfying to the reader who wants to know more (but that can be said even when more detail is provided). Even in Luke’s narrative, we are not told in what way the eyes of the disciples were kept from recognizing Jesus (Luke 24:16) and in what fashion this worked. Matthew similarly does not explain for what reason “some doubted” in 28:17. In all of these cases, the Gospel authors may be supplying suggestions of transformed physicality like we see scattered across the resurrection narratives. But the precise ways in which they make these suggestions vary. Mark is consistent with this tendency. If only we assume what needs to be demonstrated—that this is both a reference to the story of Luke 24 and an epitome borrowing from the textual version of the same—are we led to the conclusion that Kelhoffer’s explanation is why this three-word phrase appears here. The evidential basis for making such assertions is rather slender otherwise.

The other supposed seam appears in v. 13. Specifically, Mark uses τοῖς λοιποῖς, of which Kelhoffer says, “The similar contexts of Luke 24:9 and Mark 16:13 suggest that the LE’s author mimicked the Lukan τοῖς λοιποῖς.”83 The seam comes in the apparent lack of clarity:

Who “the rest” are in contrast with the group that, according to Mark 16:10—11, listened to Mary Magdalene is not specified. An interpretation based solely upon the LE’s context is probably not what this author intended, because τοῖς λοιποῖς would then designate a group other than those who grieved over Jesus’ death in vv. 10—11. For lack of an object similar to τοῖς μετ’ αὐτοῦ γενομένοις πενθοῦσι καὶ κλαίουσιν (16:10), the author of the LE seems to have written τοῖς λοιποῖς without realizing the implications of this designation relative to those already mentioned in Mark 16:10. This author probably intends for τοῖς λοιποῖς to indicate the remainder of Jesus’ followers who had not heard Mary Magdalene’s report. In the final analysis, however, his desires both to emulate Lukan style and to mirror the structure of 16:10—11 result in an incoherent narrative.84

The first claim is confusing because the contexts of the sentences in Mark and Luke are different. They are not far apart, but Luke 24:9 relates the aftermath of the discovery of the empty tomb while Mark 16:13 relates the aftermath of a second narrated appearance. We were just told that the previous verse drew from a later section of Luke 24, but now we are suddenly switching back. Of course, this is by no means the most incredible such shift Kelhoffer proposes. Nor has it been something his argument is attentive to, since it is not as if the contexts of Mark 16:9 and Luke 8:2 are that similar.

The second claim shows how once again Kelhoffer prefers convolution to simplicity in his solutions. The apparent incoherency arises from his impression that “the rest” are some separate, non-overlapping group relative to those Mary Magdalene spoke to. If one presumes “the rest” is a group more similar to Luke 24:9, I can see why he might think that, but there is no basis for making that leap without begging the question in the first place. The simplest and most obvious solution is that “the rest” are the other disciples, those who do not include the two Jesus just appeared to. There is nothing incoherent about it.85

And He Said

Yet another attempted connection with Luke 24 comes with v. 15. This connection is supposed to consist of the first three words: καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς. This is a rather common introduction of speech, and he notes six other times it appears in this same order in Mark (1:17; 2:19; 4:40; 9:29; 10:14; 14:24), though one could add other instances where the conjunction is different, missing, or further removed from the verb (7:6; 8:34; 9:36; 10:3, 5, 36, 38–39; 11:29; 12:15, 17, 43; 14:16, 48). You might think that such a common element is not something that calls for a distinct source, but that would show that you have not gotten into the mindset of this study. Instead, Kelhoffer asserts:

Closer to the context of the LE is Luke 24:46—49, where καὶ εἶπεν αὐτοῖς introduces a final statement of Jesus before he is taken up into heaven (cf. Luke 24:50—51, Mark 16:19). Although one would not commonly look for a source for such a common introduction of direct speech, the fact that the LE’s author emulates Luke 24 on other occasions raises the possibility that the introduction to Jesus’ final words in Luke provided him with the means for making his own addition resemble another esteemed tradition.86

Of course, we have seen that other identified links with Luke 24 have been weak. As such, using them as a basis for identifying this common element as being from a source is also logically suspect.

All the World

Another aspect of v. 15 that Kelhoffer links to other texts is the description of Jesus’s commission for the disciples when they go “into all the world” (εἰςτὸνκόσμονἅπαντα). Despite Kelhoffer’s earlier cited characterization of this (supposed non-Markan) author as someone who read Mark very closely, he says this phrase shows him to be “someone who used Mark’s vocabulary but who did not consistently emulate the evangelist’s syntax.”87 This is because Mark used a different adjective in the astronomically high two cases of 8:36 and 14:9—remember when one or two cases was not enough to establish style?—and because, “The three times Mark uses ἅπαντες/ἅπαντα are substantive occurrences of the adjective rather than the adjectival as occurs, for example, in τὸν κόσμον ἅπαντα.”88

How, then, did this construction arise? In this case, Kelhoffer cannot point to one specific text because the precise construction does not appear anywhere else in the Gospels. But when it comes to connecting this ending with other Gospels, we have already established that precedent only needs to be what Kelhoffer considers close enough. After identifying similar phrases in Matt 28:19; Luke 24:47; Mark 13:10; and 14:9, he avers, “Mark 13:10, along with the commissionings of Luke 24:47 and Matt 28:19, probably motivated the LE’s author to combine the wording of three verses (πάντα τὰ ἔθνη) with Mark 14:9 (εἰς ὅλον τὸν κόσμον) in an effort to make the LE’s commissioning resemble other esteemed accounts.”89

I have implicitly responded to the first point already. This text is practically synonymous with those expressions in any case. The second point is also a non-starter, provided we do not assume this use is ruled out from consideration at the start. All of the Gospel authors who use this term multiple times use it both ways (the exception being John, who, depending on the variant, used the term once in 4:25), and Mark would not be inconsistent with this if 16:15 is at least allowed to be considered. The third point again shows how Kelhoffer prefers a convoluted solution to a simple one, which is that Mark wrote this similar expression himself. Against Kelhoffer’s reasoning elsewhere, Mark 1:1–16:8 does not define the boundaries of the terms Mark was capable of writing.90

Jesus as Lord

Kelhoffer also designates the identification of Jesus in v. 19 as a sign of depending on another text: “On the one hand, Mark never refers to Jesus as ὁ κύριος. Nine occurrences of this title of Jesus in John 20—21 indicate where the author of the LE probably borrowed the title. Thus, while readers familiar with only Mark may find ὁ κύριος an unusual expression, those familiar with the narratives of John 20—21 would probably also find the title a welcome conclusion to Mark’s Gospel.”91 It is true that no other text in Mark identifies Jesus as “the Lord Jesus.” But would that not be an appropriate development for the conclusion of the Gospel in light of the narrative development (cf. John 20:28)? Still, Jesus is identified as “Lord” indirectly (though not obscurely) in 1:3; 2:28; and 12:36–37. People also refer to him in this way in the context of healing (7:28; 9:24; cf. 11:3). Whether or not all of these uses have the same sense as 16:19, and I am not arguing that they do, they nevertheless show that Jesus is identified as “Lord” elsewhere in the Gospel.92

Cited from Other Texts in the Gospels and Acts

The Exorcism of Mary Magdalene

The first example in this category is one we have already mentioned. Namely, Kelhoffer identifies Luke 8:2b as the source of the description of Mary Magdalene in Mark 16:9b.93 The descriptions from Mark 16:9 and Luke 8:2 are as follows:

Mark 16:9: παρ’ [ἀφ’ in most mss] ἧς ἐκβεβλήκει ἑπτὰ δαιμόνια