Did the Other Gospels Depend on John?

(avg. read time: 21–43 mins.)

Last year, George van Kooten advanced an argument not only for the Gospel according to John being pre-70 but also for the other Gospels being dependent on it. Not being part of the British New Testament Society, I was obviously not privy to all the details of the argument, but you can find an outline available online (you can also see some reflections and commentary by Ian Paul here). This is clearly of interest to work I have done on synoptic Gospel comparison. I will briefly respond to the idea that John was written pre-70, but most of this post will concern the outlined claims for the other Gospels being dependent on a written John.

Was John Written Before 70?

As Paul observes in his post on van Kooten’s arguments, he is far from the first to say John was written before 70. Some of the examples appear in van Kooten’s citations, and there are others still. Depending on how longeval John was, elements of eyewitness memory—see here, here, and here—could support a range of dates before and after 70. I have noted elsewhere accurate recollections of detail, including geographic and chronological. As one example in the latter vein, John recalls a dialogue between Jesus and Jewish leaders, wherein the latter saythat it has been forty-six years since the temple’s reconstruction at the first Passover of Jesus’s ministry (2:20; on this larger story, see here as well). This work was completed in 19/18 BCE (Ant. 15.380–425). As there is only one celebration marking this construction (15.421–423), it is reasonable to think that both the temple itself and the enclosures were completed around the same time, and so there are not two potential dates to reckon from. This would place this Passover after Jesus’s baptism in either Nisan, 29 or Nisan, 30 CE. This, in turn, agrees with Luke’s dating of Jesus’s baptism sometime in the fifteenth year of Tiberius’s reign in 28 or 29 CE (see here).

The most significant details in this regard are those details that would not have been available to someone who knows nothing of Jerusalem pre-70. As the citations, as well as Paul’s commentary, make clear, John 5:2 figures prominently in this point. John recalling five porticoes at the pool of Bethesda is not information someone would have known after 70, as the area would no longer be extant as it was back then. It was not until the nineteenth century that there was physical confirmation of a pool being there, and it was not until the latter half of the twentieth century that the structure was clarified, which fits John’s description. That same text also refers to the Sheep Gate, which was built in the time of Nehemiah (3:1, 32; 12:39) and was no longer extant after the destruction of Jerusalem. John writes of the pool in the present tense, and while the Gospels all use the “historical present,” this is not an appropriate description of the present here, as it is more fitting for actions.

Was Luke Dependent on John?

While van Kooten’s particular theory of the Gospels presents John as pre-70 and Luke as post-70 (as he thinks he was dependent on Josephus), and thus the relationship of dependence can only go the obvious way, van Kooten proposes examples of internal evidence that are supposed to be demonstrative of the same. Specifically, he cites Luke 7:37–38 // John 12:3; Luke 22:50 // John 18:10; Luke 23:4, 14, 22 // John 18:38; 19:4, 6; Luke 23:53 // John 19:41; Luke 24:9–12 // John 20:1–10; Luke 24:36–40 // John 20:19–20, 24–28. These are supposed to be cases of striking verbal parallels where Luke and John agree with each other but not with Matthew and Mark.

As a general point, I should reiterate what I have shown elsewhere about the degrees of similarity between the Gospels. These figures are likely to be subject to minor revision in the future as they already have been, although the absolute similarities are less likely to be revised than the weighted similarities. With that caveat, here are the figures as I have tabulated them to this point:

Matthew’s similarity to Mark: <4,752/10,616 (A)[~44.8%]; <5,683.75/10,616 (W)[~53.5%]

Matthew’s similarity to Luke: <4,324/12,234 (A)[~35.3%]; <5,296.25/12,234 (W)[~43.3%]

Matthew’s similarity to John: <485/2,505 (A)[~19.4%]; <656.75/2,505 (W)[~26.2%]

Mark’s similarity to Matthew: <4,752/10,876 (A)[~43.7%]; <5,685.75/10,876 (W)[~52.3%]

Mark’s similarity to Luke: <3,096/8,975 (A)[~34.5%]; <3,854.5/8,975 (W)[~42.9%]

Mark’s similarity to John: <407/2,118 (A)[~19.2%]; 550.25/2,118 (W)[~26.0%]

Luke’s similarity to Matthew: <4,324/11,664 (A)[~37.1%]; <5,301.75/11,664 (W)[~45.5%]

Luke’s similarity to Mark: <3,096/8,669 (A)[~35.7%]; <3,856.75/8,669 (W)[~44.5%]

Luke’s similarity to John: <312/2,059 (A)[~15.2%]; <439.25/2,059 (W)[~21.3%] (counting Luke 5/John 21: 336/2,266 (A)[~14.8%]; 483/2,266 (W)[~21.3%])

John’s similarity to Matthew: <485/2,885 (A)[~16.8%]; <657.25/2,885 (W)[~22.8%]

John’s similarity to Mark: <407/2,701 (A)[~15.1%]; <555.25/2,701 (W)[~20.5%]

John’s similarity to Luke: <312/2,657 (A)[~11.7%]; <438/2,657 (W)[~16.5%] (counting Luke 5/John 21: 336/3,062 (A)[~11.0%]; 484.25/3,062 (W)[~15.8%])

These numbers are focused only on parallels, and so the denominators are derived from word counts in parallel pericopes, rather than the totals for the Gospels as a whole. The initial numerators derive from words that are absolutely similar between the pairs of Gospels while the second numerators add “weighted similarities,” which consist of different forms of the same words or synonyms/synonymous expressions within parallel pericopes. For the details of my tabulations, you can see the tables here (though the tables are exclusive to paid subscribers and will need some minor updates).

According to Paul’s post, “In his conclusion, van Kooten made the bold claim that we should reconsider described Matthew, Mark and Luke as the Synoptics, with John in a separate category—and instead consider John, Mark and Matthew as the Synoptics, with Luke as the outlier!” While van Kooten might try to make sense of that with his peculiar ways of dating the Gospels, the fact remains that the first three Gospels are rightly called the Synoptics when one considers their degree of closeness compared to John. I have highlighted the degrees of similarity between all the other Gospels and John; notice how none of them come close to the similarity each of the Synoptics share with each other. At the very least, if we are going to suggest that other Gospels were dependent on John, the lexical evidence shows that this supposed dependence was less on John than on any other Gospel. What is more, in the specific case of Luke and John, which we are examining first, this is the lowest degree of similarity in terms of raw numbers of similarities or percentage of similarities that we see between any two Gospels.

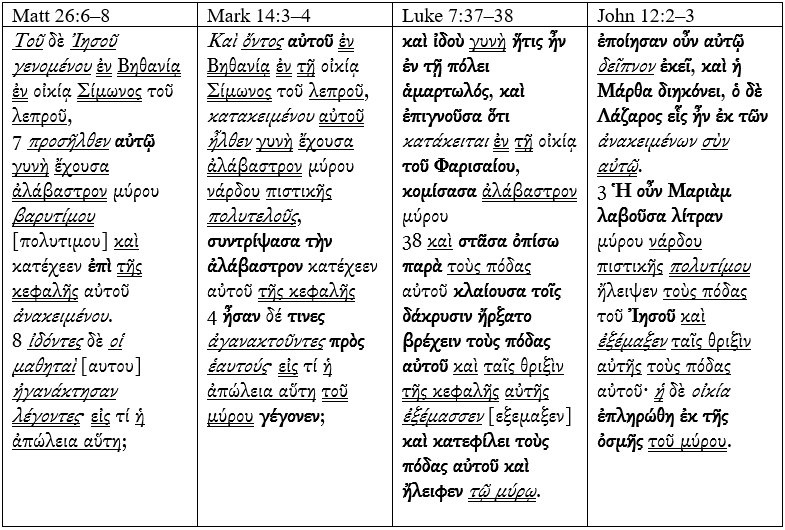

Is there anything, then, in the cited examples which suggests that the general impression is misleading? For each of the examples, we will first present them in context and then focus on the specific points van Kooten identifies. First, let us consider the similar stories of a woman anointing Jesus:

As the attached table shows, Luke is the least similar to all of the other Gospel versions, and the absolute similarities account for less than 10% of the words. These appear to be due simply to expected common elements of two stories of women doing similar actions to the same recipient. The texts van Kooten focuses on contain the only cases of Luke and John uniquely sharing elements among the 215 words of Luke’s account and the 143 words of John’s account. For the sake of completeness, I include the other two versions here as well:

There is technically an unmarked similarity here with ἤλειφεν in Luke and ἤλειψεν in John, but in the fuller version of this table I passed up marking it because there is a closer match in verb form later in Luke’s narrative. It is also a verb they uniquely share for referring to the woman’s action, while Matthew and Mark use κατέχεεν. The other elements uniquely and absolutely shared by Luke and John consist of the following words: τοὺς πόδας καὶ τοὺς πόδας ταῖς θριξὶν αὐτῆς. This is the order the elements appear in Luke but not in John. Another similarity present in modified form is the verb ἐξέμασσεν in Luke and ἐξέμαξεν in John. A minority of mss conform the verb in Luke to the one in John or to Luke 7:44, but the vast majority of diverse witnesses differentiate the forms.

The surrounding narrative should make clear that the contexts and settings of these stories are quite distinct. The history of interpretation has seen one view draw them closer together by identifications of Mary Magdalene with the woman in Luke 7 and with Mary the sister of Lazarus. The validity of such identifications is besides the point here, but that was one way of explaining the similarity of such details as van Kooten identifies. A more mundane explanation is the simple recognition that both stories involve common customs of a servant’s hair being used (or a servant using their own hair) in such cleansing actions. Luke and John focus on feet for different reasons (in part due to different settings, and probably in part due to different thematic emphases), which in turn distinguishes them from how Matthew and Mark present the story they share with John. Furthermore, each of the more unusual linguistic elements (i.e., not involving the conjunction and pronoun) are repeated by Luke in the course of the story to an extent that they are not by John. It is far from obvious, especially in light of Luke’s many, many differences in narration from the other Gospels, that one should see this brief commonality as being due to dependence on a textual source.

What about the second case of Luke 22:50 // John 18:10? Once again, the larger texts they are part of are less similar to each other than any of the Gospel pairings are to one another. But again, here they are in context:

Now let us focus on the part van Kooten draws attention to:

Once again, van Kooten has focused on the only section with absolute similarity uniquely shared between Luke and John, this time consisting of only two words: τὸ δεξιόν. This is an illustration of how strained source criticism can be when users of it demand that two words be accounted for by either a textual source or the author’s redaction of a textual source. Where Luke overlaps with John because his text overlaps with the others, he uses a different (though synonymous) initial verb, lacks another one in John, uses yet another with the same form as it appears in Matthew and Mark, and has a different form for referring to an ear than the other Synoptics or John use (which Luke will later use in v. 51). Nor is there any obvious redactional touch here fitting with specifically Lukan tendencies, lest one should beg the question and assume that every similarity is due to a source relationship and every dissimilarity is due to use or redaction of a source.

As for the two words here, this is in fact the first time John uses the term out of only two occurrences in his Gospel (cf. John 21:6), whereas this is certainly not the first time Luke uses the term in his account (cf. Luke 1:11; 6:6; 20:42; 22:69; 23:33). One can thus hardly account for this similarity as Luke taking over peculiar Johannine terminology. Unlike the differentiated focus with Matthew and Mark the previous time, this is simply a case where those other Gospels do not specify which ear. Is a single textual source needed to identify the ear? Or could this be a memory for which textual mediation was not required for the authors to be aware of it? It is simpler and more likely to think that this is a minor detail independently affirmed by both texts, rather than that these two words can only be accounted for by one author or the other breaking tendency with differentiating from the supposed textual source in order to depend only on it here.

The third example comes from scattered texts in Luke 23:4, 14, 22 // John 18:38; 19:4, 6. Here, the parallels get more complicated, as illustrated by these larger tables.

What, then, is van Kooten focusing on that is supposed to specifically attest to Lukan dependence on John? It is a particular kind of phrase that appears in different forms three times in Luke and three times in John:

Luke 23:4: ὁ δὲ Πιλᾶτος εἶπεν πρὸς τοὺς ἀρχιερεῖς καὶ τοὺς ὄχλους· οὐδὲν εὑρίσκω αἴτιον ἐν τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ τούτῳ.

John 18:38: λέγει αὐτῷ ὁ Πιλᾶτος· τί ἐστιν ἀλήθεια; Καὶ τοῦτο εἰπὼν πάλιν ἐξῆλθεν πρὸς τοὺς Ἰουδαίους καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς· ἐγὼ οὐδεμίαν εὐρίσκω ἐν αὐτῷ αἰτίαν.

Luke 23:14: εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτούς· προσηνέγκατέ μοι τὸν ἄνθρωπον τοῦτον ὡς ἀποστρέφοντα τὸν λαόν, καὶ ἰδοὺ ἐγὼ ἐνώπιον ὑμῶν ἀνακρίνας οὐθὲν εὗρον ἐν τῷ ἀνθρώπῳ τούτῳ αἴτιον ὧν κατηγορεῖτε κατ’ αὐτυοῦ.

John 19:4: Καὶ ἐξῆλθεν πάλιν ἔξω ὁ Πιλᾶτος καὶ λέγει αὐτοῖς· ἴδε ἄγω ὑμῖν αὐτὸν ἔξω, ἵνα γνῶτε ὅτι οὐδεμίαν αἰτίαν εὑρίσκω ἐν αὐτῷ.

Luke 23:22: ὁ δὲ τρίτον εἶπεν πρὸς αὐτούς· τί γὰρ κακὸν ἐποίησεν οὗτος; οὐδὲν αἴτιον θανάτου εὗρον ἐν αὐτῷ· παιδεύσας οὖν αὐτὸν ἀπολύσω.

John 19:6: Ὅτε οὖν εἴδον αὐτὸν οἱ ἀρχιερεῖς καὶ οἱ ὑπηρέται ἐκραύγασαν λέγοντες· σταύρωσον σταύρωσον. λέγει αὐτοῖς ὁ Πιλᾶτος· λάβετε αὐτὸν ὑμεῖς καὶ σταυρώσατε· ἐγὼ γὰρ οὐχ εὑρίσκω ἐν αὐτῷ αἰτίαν.

If you review the tables above, you will notice there are substantive parallels between the context of Luke 23:22 and an earlier part of John 18, but there is indeed a similar phrase used in John 19:6, and there is a call to crucify like we see in Luke 23:21. That would seem to be a signal of incidental similarity of detail as authors recall similar parts of the story. Likewise, I do not have in my tables a listed parallel of the contexts of Luke 23:14 and John 19:4, and that is because the contexts are too different in wording to clearly function as parallels. As it is, absolute verbal similarities are hard to come by between these two texts with only the preposition linking them in this fashion. All other words are differentiated in some way.

In any case, let us go through them. What van Kooten identifies as the case of dependence is the repeated declaration that Pilate found no cause in Jesus for doing what the Jewish leaders demand in executing him. The wording varies each time it appears in Luke and John (though it should be noted that in Luke 23:14 Nestle-Aland has chosen a distinctly minority reading for the negative). As such, what is supposed to be striking about these parallels is simply in the eye of the beholder. The variation comports with variation that comes from oral recitation, or in everyday situations of recalling stories for that matter. There is no clear reason to think that the threefold repetition can only be due to textual borrowing plus revision for most of the words involved every time.

The fourth case is simpler in Luke 23:53 // John 19:41. As usual, here they are in their larger contexts:

And here is what it looks like when we zoom in:

Overall, the account of Luke is not remarkably closer to John than to the other Synoptics, nor is John closer to Luke than to Matthew. Even here, Luke is overall closer to the other Synoptics in verbiage, but the only element that stands out in relation to John is the detail that the tomb was one where no one had ever been laid. Most mss have a reading in which Luke more closely matches John’s wording (though not the order). Only John (in agreement with Matthew) describes it as “new,” but the point remains the same. With the variations in word order and phrasing, particularly in the different verb used, and considering again that Luke is not markedly close to John in any other respect in their parallel texts, is there any reason we should not think that they are independently recalling a common detail? Otherwise, this is the only detail in wording that they come close to each other on in distinction from the other Gospels. Nor is there anything peculiarly Johannine about the shared descriptor.

The fifth case is cited loosely— Luke 24:9–12 // John 20:1–10—but it really concerns the following detail in Luke 24:12 that is shared with John and none of the other Gospels (which cannot be said of anything else in Luke 24:9–11 paralleled by John 20:1–10):

The shared language is at least more interesting here. Seven consecutive words provide the longest chain of verbatim similarity, although the chain is only uninterrupted in Luke’s shorter version. Some of the vocabulary is unusual, but it is unusual for both Gospels, as the use is driven by the situation, which is obviously not regular for the course of the narrative to this point. Nothing particularly (more) characteristic of one author has been taken over by the other against his own tendencies, nor are the dissimilarities clearly the result of supposed redaction to make the text in line with the author’s tendencies.

Of course, this illustrates how much these claims of textual dependence amount to Rorschach tests depending on assumptions one brings. One who is inclined to see John as later than Luke will see this as John expanding Luke. One like van Kooten who is inclined to see Luke as later than John will see this as Luke condensing John and telling a much more streamlined story. Consideration of a source in shared memory is ignored. John is closer to Luke than he is the other Gospels specifically in this section on the empty tomb. The following figures are based on Matt 28:1–8 // Mark 16:1–8 // Luke 24:1–12 // John 20:1–18:

Matthew’s verbal similarity to Mark: <39/136 (A); <53/136 (W)

Matthew’s verbal similarity to Luke: <22/136 (A); <33/136 (W)

Matthew’s verbal similarity to John: <14/136 (A); <25.5/136 (W)

Mark’s verbal similarity to Matthew: <39/135 (A); <52.5/135 (W)

Mark’s verbal similarity to Luke: <27/135 (A); <34.75/135 (W)

Mark’s verbal similarity to John: <23/135 (A); <33.25/135 (W)

Luke’s verbal similarity to Matthew: <22/159 (A); <33/159 (W)

Luke's verbal similarity to Mark: <27/159 (A); <34.75/159 (W)

Luke’s verbal similarity to John: <36/159 (A); <46.25/159 (W)

John’s verbal similarity to Matthew: <14/225 (A); <25.5/225 (W)

John’s verbal similarity to Mark: <23/225 (A); <33.25/225 (W)

John’s verbal similarity to Luke: <36/225 (A); <46.25/225 (W)

As I have shown with reviewing the Synoptic versions elsewhere, none of these versions are especially close together lexically speaking. And what we see in the text we are focusing on here is the longest string of verbatim similarity in either Luke or John. The peculiar amount of similarity in this particular section is just as well explained by the shared memory with a minority of verbatim similarities that explains the accounts more generally. Luke may have been particularly reliant on the memory of the women here, possibly with a mix of what he learned from Peter, sources which would have shared memory with John, per his own account. Since these accounts are the only ones to interact with the empty tomb beyond the initial discovery (unless one counts Matthew’s tangential account of 28:11–15), they are the only ones to share the detail of another visit and of a stooping down to look in the tomb. As some of the vocabulary (besides the main verb) consists of unusual terminology, it is less surprising that the wording as such was less flexible than other recitations of detail, and so it was not so much varied by synonymous expression as by inclusion or omission of other details. There is no reason this could not have been a shared piece of memory as opposed to a detail that demands a textual source.

As for the sixth and final example, that is something I have already addressed previously. The previous time, García posited that the broad similarities of these versions meant John was dependent on Luke, but this time it is the other way around, as van Kooten even claims that Luke “de-Johannizes” the story by referring to Jesus’s feet rather than his side in the case of the Thomas episode. There are enough commonalities here to give us reason to think that John and Luke are referring to the same event while supplying different details, but unless one comes to the texts already assuming a relationship of textual dependence, it is not clear that one needs to posit a relationship of textual dependence to account for the commonalities.

Was Matthew Dependent on John?

At least in this outline, van Kooten is not specifically exploring the question of Markan dependence on John. According to Paul’s report, he referred to his work elsewhere in claiming that Mark was written approximately around the time of the destruction of Jerusalem, and since he thinks John was written earlier, that would settle the matter of who knew whose work, if one needed to know the other’s work [update: I have seen in other work from van Kooten, particularly his latest article in Novum Testamentum 67, that he does not think Mark was familiar with John’s Gospel]. But for Matthew specifically, he cites a number of parallels: the so-called “thunderbolt from the Johannine sky” in Matt 11:25–27 // Luke 10:21–22; Matt 10:24 // John 13:16 and 15:20; Matt 10:40 // John 13:20; Matt 27:29 // John 19:2; Matt 27:57 // John 19:38; Matt 27:60 // John 19:41; Matt 28:9–10 // John 20:14–18.

The first text is said to parallel John 3:35 and 10:15, while van Kooten also notes 7:29; 13:3; 17:2, and 25. The noteworthy similarities here do not consist of terminological connections, as these are sparse or consist of frequently used terms. The parallels are conceptual and thematic. But if that is the case, why is it necessary to posit a textual relationship of dependence here? Could it not be that this is the sort of thing Jesus said, and so authors reflected memory of this in distinct but similar ways? That makes better sense of the mix of similarities and differences than positing obscure(d) textual dependence.

The second case is closer terminologically, but the common notion of a servant not being greater than his master (or an apostle than the one who sent him) is again expressed in distinct ways. Nor is it clear why such a case of textual dependence should only exist for this kind of phrase in a completely distinct context. More likely, again, is that Jesus made this kind of statement on multiple occasions (as he did even within the parameters of the Johannine text), and it fit with his broader teaching about his disciples and servants being like him. The case for textual dependence is straining at a gnat here.

The third case is more interesting, as I have categorized it under scattered/free-floating logia or descriptions. That is, certain parallel sayings and descriptions that constitute a single sentence in at least one source appear in multiple contexts, as we see here:

Matthew’s text appears in a context different not only from John but from the other Synoptics as well. Mark and Luke do not parallel each other at all, except in the unmarked instance of the second-person pronoun ὑμᾶς, which is simply incidental. One who is dedicated to the notion that similarities must be the result of textual dependence can make the case that all of these texts are drawing from Matthew or that Matthew is drawing from all of these texts (or one could make a more complicated case as well). Why any of these scenarios of textual dependence might have happened, considering that the context is different every time, is not clear. Yet again, it is more probable that these are the kinds of statements Jesus made on multiple occasions, and the Gospels reflect that fact in their own ways and contexts.

The fourth and sixth cases come down simply to Matthew and John mentioning certain details. I have already observed the latter similarity in their reference to the tomb being new, while the former is that they both reference Jesus’s crown of thorns (see also Mark 15:17). It is as arbitrary to say that these details must have come from John as it is to say that they must have come from Matthew (or, in different form, form Mark and Luke).

The fifth case concerns how Matthew and John refer to Joseph of Arimathea. Mark and Luke refer to him as one who was anticipating/waiting for the kingdom of God (Mark 15:43 // Luke 23:51) while Matthew and John refer to him in different ways as discipled to Jesus (ὃς καὶ αὐτὸς ἐμαθητεύθη τῷ Ἰησοῦ in Matt 27:57 vs. ὢν μαθητὴς τοῦ Ἰησοῦ κεκρυμμένος δὲ διὰ τὸν φόβον τῶν Ἰουδαίων in John 19:38). Each of the Gospels has a way of recalling Joseph’s affinity to Jesus, but Matthew and John are more synonymous to each other as they invoke the same root concept with verbal and nominal cognates. I have displayed the overall similarities and dissimilarities between these texts above. Matthew’s version is closest to Mark’s, but beyond that, none of the texts are especially close to each other. If Matthew was dependent on John, and this is somehow only evident in the two instances of this description of Joseph and the description of the tomb as “new,” one must wonder why Matthew has redacted a text to an unusual expression for him rather than following his supposed source in using terminology that is much, much more common for his work. One also must wonder why Matthew would completely skip over any statement like John’s that indicates conflict with other Jews, since that would fit a theme in Matthew’s work. If both are recalling a detail in their own words, that makes sense of the mix of similarities and differences. But if one text is dependent on the other, these facts are rather more difficult to explain.

The final case is taken as a reference to the same story, although this is not necessarily so. They are similar in that they both reference women laying hold of Jesus, but they use different vocabulary. If Matthew was dependent on John, it would not have been against his tendencies to retain the same vocabulary. Nor is it obvious that these two texts are referring to the same story (at least, in their entirety). As we have seen in my series on evaluating harmonies of the resurrection narratives, it is not clear if Mary Magdalene is to be included with the women in Matt 28:9–10. She may be separate from them, as is often supposed. I think it is at least a possibility that Matthew could be compressing and/or conflating multiple encounters here by narrating only one appearance to the women as a kind of catch-all for multiple appearances, as may be hinted by how the description van Kooten highlights of the women taking hold of Jesus in Matt 28:9 and Jesus’s instruction to cease grasping in John 20:17 fit together (though the correspondence is not precise on the linguistic level). One can see from Acts 1:1–11 that Luke similarly compresses his narrative in Luke 24:36–53 (as does Mark 16, particularly in 16:14–20). But the application of that possibility here is more speculative. Whatever the case may be, though, there is not strong evidence here of textual dependence one way or the other.

Conclusion

I am inclined to agree with van Kooten that John was written before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70. Unlike van Kooten, I cannot say I am settled in my own mind about the order in which the Gospels were written. After all, I think many of the arguments based on impressions of redaction are ill-warranted.

That description includes van Kooten’s arguments here. His claims about dependence are among the more peculiar, but I cannot say they are outstandingly worse than other more popular claims of textual dependence I have seen (see here for example). They are simply illustrative of the pitfalls of all-engulfing assumptions about textual dependence without accounting for other kinds of relationships between texts or other explanations for similarities and dissimilarities.