(avg. read time: 12–23 mins.)

Earlier this year, Jeffrey P. Arroyo García published an article in Biblical Archaeology Review questioning whether Jesus was, in fact, nailed to the cross.1 Yeah, I know how it sounds, and I am aware of the backlash Christianity Today has gotten for the interview on the subject and their social media promotion of the same. But I am here to address the original article, not the interview, and I am going to lay out the case here before responding.

García’s introduction first mentions how Helena, Constantine’s mother, was said to find the nails of the cross (Ambrose, Ob. Theo. 47), and he suggests that, although other authors had referenced the nails (he cites Ignatius, Smyrn. 1:1; Justin Martyr, 1 Apol. 35), it was this event “that helped solidify the nails as part of the evolving Christian lore surrounding the crucifixion” (55). But for how prominent the detail is in iconography and the history of relics, he finds in the Gospel stories that they are “conspicuously silent about what was used to secure Jesus to the cross” (55). The verbs used for crucifixion simply refer to hanging him on the cross without specifying the means for doing so.

He mentions the Thomas episode (John 20:24–29), of course, but he stresses that this story is unique to John. Otherwise, he notes how the detail, or even reference to the wounds, is absent elsewhere. He accounts for Col 2:14 by claiming that it applies to the titulus nailed above him on the cross (55). In an endnote, he says of 1 Pet 2:24; Gal 6:17; and Rev 1:7 that they “are either alluding to the Hebrew Bible or alluding generally to ‘wounds’” (58 n. 1).

He then reviews the archaeological evidence. The most noteworthy evidence was found in 1968 at Givat ha-Mivtar in Jerusalem, where a heel bone was found in an ossuary (or bone box) with a nail pierced through it. The bones date from between the first century BCE and the First Jewish-Roman War. The inscription refers to the deceased as Yehohanan “ben hagaqol.” We need not get into the debate on the meaning of this curious phrase here, though García refers to Yigael Yadin’s proposal that it refers to the manner of his death with knees apart, a form of crucifixion depicted in the Puteoli graffito, the Alexamenos graffito, and the Pereire gem (also see here).

He mentions other examples of reference to crucifixion that did not specify nails being used before noting another archaeological find from 2017. In Fenstanton in England, excavation of a Roman-era gravesite revealed another heelbone pierced with a nail from sometime between the second and fourth centuries. Conversely, two other remains of crucifixion victims from Egypt and Italy do not show any evidence of piercing through the heel (56–57).

He briefly reviews Josephus and observes how he uses general crucifixion verbs (σταυρόω and ἀνασταυρόω) at multiple points. But when Josephus describes the crucifixions during the First Jewish Revolt, he uses a specific verb for nailing (προσηλόω). García implies, “If the Romans did indeed change their execution style during and after the First Jewish Revolt, this could suggest that earlier crucifixions, including during the time of Jesus, were carried out with ropes or other similar material” (57). In support of this, he notes the use of the verb for “hang” (κρεμάννυμι) in texts like Luke 23:39 and Acts 5:30.

What, then, does he have to say about the episode with Thomas in John? One, he thinks the Gospel was written in an area where the nailing of hands in the crucifixion was well known. Two, reiterating what he said already, there are details in John’s narrative that are unique. In this vein, he claims that:

John also appears to be rewriting Luke 24:36–43, where the disciples are directed to “touch” and “see” Jesus’s hands and feet. Of course, it is clear in Luke (v. 39) that Jesus’s hands and feet are intended to prove the resurrection and not to demonstrate the nail wounds. Therefore, John might be creatively weaving together these elements, portraying the crucifixion as real, even a fulfillment of Zechariah’s prophecy [12:10], for a community who had to believe without seeing. (58; emphasis original)

He thus claims that John refers to a style of crucifixion that “does not appear to predate the First Jewish Revolt, specifically in Judea. Therefore, this account may have come from a time after the revolt or somewhere in the Diaspora where nailing was more common, while John’s crucifixion story was adapted from his sources, likely the other Gospels” (58).

Response

There is a lot to sort through here. I cannot say that I have done a dedicated study on references to the nails in the crucifixion, so I am not aware of who all mentioned them among the early Christians, but I can say that in addition to those second-century sources García references, one could also add the Gospel of Peter 6.21. Another second-century source that comes from a hostile source is referenced by Origen in Cels. 2.55, where Celsus’s Jewish figure references the nails. These sources alone (without doing a comprehensive review) show a widespread reminiscence of nails being part of Jesus’s crucifixion in the second-century in sources spanning from Syria (Ignatius) to Rome (Justin Martyr, although he grew up in what was once Judea) to a work of unclear provenance (Gospel of Peter) to the extent that even a hostile writer knew that Christians mentioned this detail (Celsus).

Although García makes that point that nails may not have been involved in crucifixion as much as people think (58), that is only if you work on the assumption that nails were always (or practically always) used. As it is, he undersells how many ancient texts refer to the use of nails in crucifixion. If we restrict ourselves to texts up to approximately the end of the first century, and without including the NT or Josephus, since he mentions those in the article, we could find a good number of cases, some of which are ambiguous or disputable. Among the clearer ones are references going back centuries before Christ’s crucifixion. The following list is in rough chronological order:

Diodorus Siculus, Bib hist. 2.18.1 [quoting a fifth century BCE reference]; Plautus, Pers. 294–295; Most. 359–360; Varro, Men. fr. 24; Diodorus Siculus, Bib hist. 25.5.2; Lex Puteolana 2,12; Philo, Posterity 61; Providence 2.24; Dreams 2.213; Seneca, Dial. 7.19.3; Ep. 101.10; Pliny the Elder, Nat. 28.46; Lucan, Civ. bel. 6.543–547; Quintilian, Inst. 7.1.30; Plutarch, An vit. 499D

One might also add Tactius, Ann. 15.44 to this list, although the actual verbiage is ambiguous. But since he describes Christians being fixed to crosses while also being burned to death, this probably implies they were fixed with nails rather than ropes that could burn.

For more sources, one should consult John Granger Cook’s Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World.2 Some of the sources Cook reviews show that one possible reason we may not have more evidence of nails used for crucifixions is because such nails were reclaimed, and they could be used for magic (in line with the reference from Pliny the Elder). This is not to say that crucifixion victims were always nailed, of course, and for mass crucifixions the executioners probably did not have nails to use for all those they killed in this fashion, but it was common enough that nails were often used in association with crosses and crucifixions, and this was done in many sources from authors across the Mediterranean in different historical eras, none of whom in the foregoing list were Christians.

The reference to Peter’s crucifixion in Acts of Peter 39 (=Martyrdom of Peter 10) casually mentions him being “nailed” to the cross. By contrast, the Martyrdom of Andrew 15 feels the need to specify that Andrew was bound to his cross and not nailed. The latter author may thus have seen a need to avoid supporting a presumption his audience probably would have made. The later writer Eusebius also attests to Christian martyrs being nailed to crosses (Hist. eccl. 8.8.1; 8.14.13). García’s presentation is simply exaggerating Helena’s importance here.

Nor indeed is it clear how the Gospels (besides John) are “conspicuously” silent about how Jesus was secured. It is true that main verb used for crucifixion (σταυρόω) does not itself imply the means of suspense. It all depends on what the one using the verb associates with crucifixion, and it is far from obvious that the default expectation and association would be that nails were not used unless specified. Other uses of the verb and its compound ἀνασταυρόω outside of the NT may be used without reference to a cross, and they may (Herodotus, Hist. 4.103.1–3; 9.78.3) include some form of impalement or may indicate some other piercing (Josephus, Ant. 6.374), specifically where those already dead are concerned. This is a case where a reader’s expectations about nails needing to be referenced if they were meant to be involved is not an expectation in line with ancient authors and audiences. In any case, there is no tradition known from the first or second centuries that acknowledges Jesus was crucified while denying that nails were involved.

I will save addressing García’s remarks on John 20 for later. For now, I will address what he says about these other NT texts. The claim that the nailing imagery in Col 2:14 refers strictly to a titulus that claimed the nature of the crime is, to say the least, questionable. The object nailed is said to be the “handwriting,” which signifies a note of debt (colloquially, an “I.O.U.”), and this consisted of decrees against and hostile to us. But God (the subject as made explicit in 2:12) has removed this obstacle by nailing it to the cross. This does not correspond with the titulus that accompanied Jesus’s crucifixion, of course. But nor does it correspond simply to what we might imagine figuratively as the reason for his crucifixion. The debt was nailed there because the one who took it on was nailed there. The logic of our being raised with Christ (Col 2:13) depends on our sins being left on the cross where Jesus died. Our record is expunged because of Jesus’s crucifixion. It was nailed to the cross with him, and so our being consigned to the death in sin becomes our death to sin in Christ who provided our atonement. In his own stripping off his fleshly body in death, he stripped off the powers and authorities. In overcoming death by death and resurrection, he made his body, putatively something under the power of the powers of this age, the site of victory over sin, death, and their subordinates. Indeed, crucifixion was meant to make its victim a public display, a shameful exemplar of impotence serving as a reminder of who is in charge and what happens to those who try to usurp that power. But because of the vindication of resurrection, it became the site where the powers were themselves made to be a public display in their defeat. After Jesus accomplished his purpose, he came down from the cross in victory in his resurrection and exaltation, for the cross was God’s means of inaugurating the kingdom. And we participate in that victory over the powers by our participatory union in him, and thus our membership in the kingdom he inaugurated through the cross. (For more on this, and other references to the gospel and resurrection in particular in Colossians, see here.)

1 Peter 2:24 operates on this same logic while drawing more specifically on language from Isa 53 (for more on this, see here). Other such uses of Isa 53 in reference to his crucifixion in the NT implicitly link the wounds or his being pierced for our transgressions with what happened to Jesus in his crucifixion, which would imply that nails were used and not simply ropes. Galatians 6:17 and its reference to Paul bearing the marks (στίγματα) of Jesus is going to need more than a dismissive wave of García’s hand to address how it does not suggest wounds linked with crucifixion, especially in light of how Paul has so emphasized the cross in this letter. And what is the fulfillment of Scripture in Rev 1:7 if not the piercing on the cross? Just saying it refers to fulfillment of Scripture does not mean it is without a particular point of reference (if anything, that should indicate the opposite).

As for his comments on Josephus, his implications are misleading, as if there is some terminological shift that happens with narrating this particular point in history.3 He goes so far as to say in the instances Josephus refers to nailing these people to crosses, “In both accounts, Josephus jettisons the verb ‘to crucify’ and instead describes crucifixion quite simply as ‘nailed ... to crosses” (57). Those two instances he refers to are in War 2.308 and 5.451. In neither case does Josephus “jettison” the main verb he uses for “to crucify” (ἀνασταυρόω). In the first case, Josephus says Gessius Florus, among other evil deeds, had peaceable citizens maltreated beforehand by scourging them, and then he crucified them (μάστιξιν ... ἀνεσταύρωσεν; 2.306). Shortly after this in his summary review of the atrocities of that day, Josephus says Florus had done what no one had dared to do before by scourging before the tribunal and then nailing to a cross (μαστιγῶσαί ... καὶ σταυρῷ προσηλῶσαι; 2.308) citizens of equestrian rank. “Crucify” and “nail to a cross” are functioning as parallel expressions here, given their common relationship to following the action of scourging and as a reference to the actual form of execution that was not supposed to be used on a Roman citizen.

In the second case, there are multiple references to crucifixion right before and after the use of the verb “nail.” We are told that those people the Romans caught outside the besieged Jerusalem were captured, scourged, tortured, and eventually crucified (ἀνεσταυροῦντο) opposite the walls of Jerusalem (5.450). Josephus says Titus continued these spectacles of mass crucifixions in order to try inducing the Jews to surrender (cf. 5.289). But while they continued, the soldiers amused themselves by nailing (προσήλουν) prisoners in different postures. This went on for so long that Josephus says space was no longer found for the crosses (σταυροῖς) nor crosses (σταυροὶ) for the bodies. The suggestion is that they eventually resorted to crucifying without fashioning crosses. The nailing was not done only subsequent to that. Still, “nail” is once again used in parallel to “crucify,” which implies a close relationship (though not always identical, historically) between them, which is difficult to make sense of if this is something introduced to Judea only recently at this point.

Nor is this some kind of terminological shift indicating a new era of punishment. After all, we see crucifixions at other times in the war, and Josephus refers to them with standard terminology (besides what I have already noted, see War 3.321; 4.317). Since we have already seen that Josephus uses “nailing” and “crucifying” in parallel usage, one cannot exactly rule out some piercing being used in other instances. Some of his use of crucifixion terminology is certainly ambiguous and may simply refer to a hanging of exposure, as in the case of the cupbearer and the baker (Ant. 2.73, 77). We have already noted a case that did not refer to “crucifixion” as such but still depended on the imagery of hanging by piercing (Ant. 6.374). The references in the context of Esther could go either way (Ant. 11.17, 103, 208, 246, 267, 280, 290). Other cases referring to executions enacted by Antiochus Epiphanes (Ant. 12.256) and Alexander Jannaeus (Ant. 13.380 // War 1.97, 113) could go either way, but one can hardly rule out the use of nails either. Since nailing for crucifixion was known well before Antiochus, it can hardly be assumed that he would not have thought to resort to the use of the same. The scourging and crucifixion are not mentioned in 1 Maccabees, but the use of this description in parallel to what we see from Florus and Titus means that we cannot say that the use of nails would have been a bridge too far. The event referenced from Alexander’s reign is supposed to highlight his cruelty, and so one can again not rule out the use of nails or default to the idea that they were simply hanged by ropes. Varus ending a revolt with subjecting some two thousand people to crucifixion (Ant. 17.296 // War 2.75) may have involved a mix; I imagine it would have depended on the supply of nails of sufficient size. The famous Testimonium Flavianum has textual issues that we will address more fully another time, but it includes a reference to Jesus’s crucifixion (Ant. 18.64). A crucifixion Tiberius executed in Rome (Ant. 18.79) could hardly be restricted by what García suggests was a change in policy of crucifixion in Judea at a later time, especially since we see Roman writers well before this time associating crucifixion with the use of nails. In a case near the end of Gaius’s reign of a simulated crucifixion followed by a play with a murder, Josephus says that much blood was needed to simulate both the crucifixion and the murder (Ant. 19.94–95). He does not reference nails in this context, but Josephus was apparently not one to default to the idea that crucifixion only involved hanging by ropes. Tiberius Alexander (Ant. 20.102), Quadratus (Ant. 20.129 // War 2.241–242), and Felix (War 2.253) also use crucifixion to quell disorder. To say that the use of nails was some change in policy that only coincided, somehow, with the very outbreak of the First Jewish Revolt and then only again at the siege of Jerusalem stretches any sense of plausibility to the breaking point. That is not to say with certainty that they were used in all of these cases, but there is no evidence of a change in policy whereby nails could have only been used later.

We have also seen how García tries to hang much significance on the use of the word for “hang” (κρεμάννυμι) in crucifixion in Luke (23:39), as well as the later statement of Acts 5:30. One should also add the references in Acts 10:39 and Gal 3:13. But as a matter of fact, this tells us nothing in itself about whether nails were used or not, as it is entirely compatible with the use of nails. We see this in Philo, Posterity 61 and Lucian, Prom. 1 (where nails are used for crucifying Prometheus; cf. 2 and 9), and Eusebius uses the term in reference to Peter’s crucifixion (Hist. eccl. 3.1.2). Diodorus Siculus says of the men of Utica firing on their own countrymen being hanged from a siege engine so that they were nailed (προσκαθήλωσαν) thereto that their punishment was almost like crucifixion (Bib. Hist. 20.54.7). He does not use this description when they are first hanged but only when they are also pinned. Despite an apparent change in policy of crucifixion, if García’s argument is to be accepted, Josephus references how a cross was constructed for the purpose of hanging Eleazar outside of Machaerus late in the war (War 7.202).

I thus see no reason to say that to describe crucifixion as “hanging” is to assume that nails were not used. The term could obviously be used even when nails were known to have been involved. It could also be, as Gal 3:13 in particular highlights, that this terminology is used for how it resonates with the language of Deut 21:22–23. Crucifixion could sometimes be a literal hanging on a tree, but it also applies figuratively since one is placed on a wooden structure, but there were times when the hanging involved nails.

Finally, we must address what García says about John 20:24–29, since it is the most direct statement that nails were involved in Jesus’s crucifixion. He can dress it up as he wants to, but the point he is making is that he thinks John made it up. His case relies on John not being a reliable narrator or having reliable memory (for examples of accurate memory of pre-70 details not simply connected with the story of Jesus, note the chronological detail of 2:20 and the feature of 5:2).4 The fact that John is the only one who mentions this detail means nothing in and of itself. I have noted multiple occasions in which John is the only one to mention a detail where he otherwise parallels the Synoptics, but these additions amount to extra information supplied by an eyewitness (see here, here, and here). I see no reason not to include this story in that same vein of Gospel details. After all, John is the only to attribute any specific speech to Thomas prior to this episode (11:16; 14:5).

If the detail about the nail wounds is being added here as a retrojection, García has not begun to explain why it is added here only. That is, why was it not added as a detail in the actual crucifixion narrative? Are we to think that John was going along following his supposed textual sources in the crucifixion narrative (and not all that closely, as it so happens), adding details as he went, but that he suddenly forgot to mention the nails, only adding in that detail here? Or is it more likely that the detail is mentioned incidentally simply because it was an assumed part of the narrative all along?

García has not presented sufficient evidence that John is retrojecting a detail that only would have applied later in Judea, since he has not positively demonstrated that nails would not have been used at the time of Jesus. He even quickly glided over the archaeological evidence of Yehohanan being dated between the first century BCE to the end of the First Jewish-Roman War, since that range of dates implies it would make sense for him to have been crucified in this way before the war. He simply assumes, based on peculiar readings of verbs and of Josephus’s use of terminology, that this could have only applied at one extreme end of that range and not before.

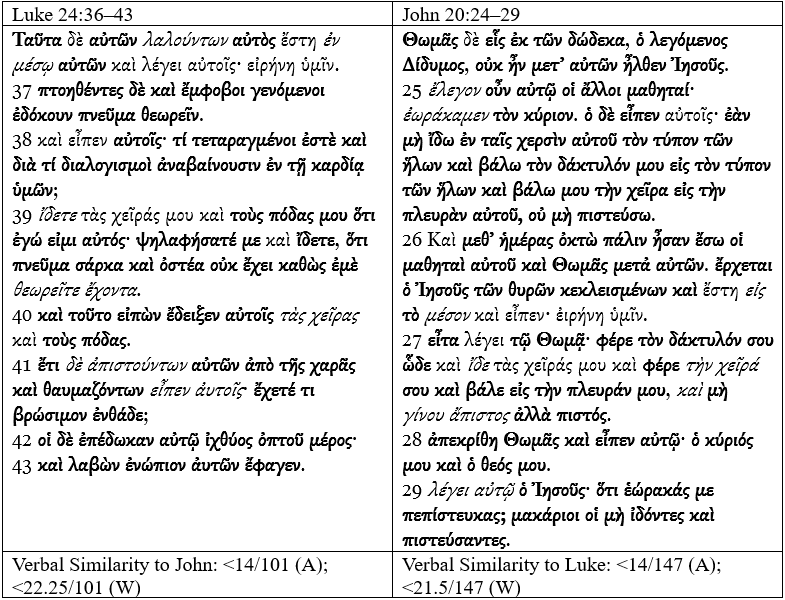

Anyone who has read through my work on synoptic comparisons will be unsurprised that his claim of John “rewriting” Luke 24:36–43 only further convinces me of the opposite of García’s claims. Using Nestle-Aland as the base text (simply for consistency) and using the method outlined in my Gospel Synopsis Commentary series, here are how the texts look side by side.

If John is “rewriting” this part of Luke, he has done so in such a way as to make it unrecognizable, save to a scholar in the twenty-first century shopping for parallels that he can claim are the result of a source relationship. We can also compare Luke’s text to the previous episode in John:

If you sort through all of this, you will see that most of the absolute similarities in John 20:24–29 are the result of terminology repeated from the previous episode. The subsequent text only has a greater number of weighted similarities because the significantly more extensive text allows for more incidental similarities. I have commented elsewhere on John and the Synoptic Puzzle (besides my Synopsis Commentary series, see here), but to make a point here, García is simply presuming that John’s narrative—and any similarities with other narratives—must be related to a textual source when there is no need to presume such (except to buttress his claims).

When García says, “it is clear in Luke (v. 39) that Jesus’s hands and feet are intended to prove the resurrection and not to demonstrate the nail wounds” (58), this is sheer rhetoric. It is not at all clear that nail wounds are not being assumed here. Showing them his hands and his feet, which is a detail John does not include, coincides with where his crucifixion wounds would be (speaking in broad terms, as they would more precisely be in the area of the wrists and probably ankles). The fact that the hands and feet are supposed to identify him mean that there are some distinctive features there that carried over after his death. Luke may also imply such identifying marks when he mentions how the two disciples recognized him in the breaking of bread (24:30–31, 35), wherein he would have shown his hands. The further command to handle/feel is to show that these features are solid and not illusions.

I know I have written something much longer than García’s original article. But like I said, there was a lot to sort through. He has not come anywhere close to giving sufficient reason for doubting the veracity of John’s testimony that Jesus was, in fact, nailed to the cross, which is what is necessary for accepting García’s suggestion. Nails being used in Jesus’s crucifixion is not a prominent detail in the Gospels or the rest of the NT, but there is no reason to jettison the detail either, since it is a part of Jesus’s history.

Jeffrey P. Arroyo García, “Nails or Knots: How Was Jesus Crucified?,” BAR 51.1 (Spring 2025): 55–58.

John Granger Cook, Crucifixion in the Mediterranean World, 2nd ed., WUNT 327 (Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019).

“In discussing various Roman atrocities during the First Jewish Revolt, however, Josephus noticeably uses a different verb, namely, “to nail” … when describing Roman crucifixion” (57).

I want to address the dating of John another time, as it is besides the point here. I think John was pre-70, the majority tends to place it late in the first century (usually the 90s). But it is irrelevant to get into those details here because, regardless, there is some gap of time between when the events happened and when it was written down (not that it affects reliability, but in that most mundane sense, the text was written “later”), and even on the latest date one might assign to John, García’s argument is not going to hold water.